Link.

advertisement

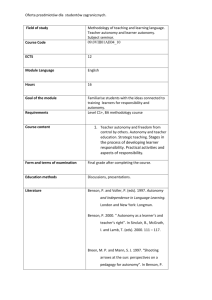

1. SLIDE #1) Thanks for that introduction. Before getting start, I’d like to thank my collaborators on the project, first my advisor, Joe Allen, and also my fellow graduate students Dave Szwedo and Megan Schad. Also, if you are interested, feel free to check out additional research from our lab at www.teenresearch.org. a. So today, as mentioned, I am going to be focusing on peer foundations of important psychosocial outcomes in late adolescence and young adulthood 2. SLIDE #2) To begin, I’d like to review the broad theoretical framework from which this study operates. Self-Determination Theory suggests three basic human psychological needs that provide the foundation for positive self-motivation and personality development— relatedness, autonomy, and competence (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1985, Ryan, 2000). According to this theory, social contexts that inhibit satisfaction of relatedness, autonomy, and competence needs tend to discourage individuals’ inherent motivations and produce negative developmental and psychological outcomes (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000) 3. SLIDE #3) We are going to be focusing on the establishment of autonomy and relatedness during disagreements with close others, which has been shown in previous research to be an important developmental task. a. In the way that we conceptualize the constructs, adolescent autonomy may be established by asserting one’s opinions in a confident, reasoned manner, while relatedness is maintained by expressing warmth, validation, and a collaborative approach to handling disagreements. 4. SLIDE #4) Establishing autonomy during disagreements while also maintaining a sense of relatedness predicts a range of positive adolescent psychosocial outcomes including higher self esteem, ego development, attachment security, and lack of depressive symptoms (Allen & Hauser, 1996; Allen, Hauser, Bell, & O’Conner, 1994; Allen et al., 2006), and at least in some contexts, adolescents who display high levels of autonomy in family disagreements also tend to have closer friendships and higher levels of social acceptance. a. Additionally, studies typically find that autonomy and relatedness are highly positively correlated and that it is the combination of the capacity to establish autonomy while maintaining relatedness that has shown the strongest relation to psychosocial functioning in adolescence 5. SLIDE #5) A lot of this previous research has focused on the establishment of autonomy and relatedness within the family, and in fact at least one study has found that an inability to establish autonomy with parents predicts future depressed affect. However, this area of research has concentrated less on this important developmental task within adolescent friendships. During adolescence, teens increasingly rely on their friends for support, they spend more and more time with their friends as adolescence progresses, and some roles that parents used to take on, friends begin to fill during adolescence. 6. SLIDE #6) So the next step then becomes trying to find figure out how a lack of autonomy and connection within adolescent close friendships predicts important psychosocial outcomes, such as interpersonal competence, depression, and social withdrawal. 7. SLIDE #7) Adolescent depression has been repeatedly linked to broad markers of problematic peer relationships, whether problems are assessed as rejection, lack of popularity, or lack of interpersonal support. Relatively little is known, however, about what exactly is going wrong within adolescent close friendships that portends a risk for future difficulties. As mentioned, very little research has explored the specific link between a lack of autonomy and connection with close friends in adolescence and later depression. One exception is the finding that teen behaviors undermining relatedness with peers during conflict were found to predict short-term increases in depressive symptoms from age 13 to age 14 a. Additionally, little research has studied this phenomenon in terms of long-term adjustment, particularly in the context of the critical transition to young adulthood. Given that the greatest increases in depressive symptoms occur from early adolescence into young adulthood, understanding the processes that may create risk of such developing symptoms during this period is essential 8. SLIDE #8) There is also research, albeit somewhat indirect, to suggest that a lack of autonomy and connection with friends would relate to social withdrawal as well. Child and adolescent social withdrawal has also been concurrently and prospectively associated with peer difficulties, including peer neglect and rejection, friendlessness, peer victimization, and low friendship quality. a. Given that socially withdrawn children and adolescents tend to fear negative evaluation from others already, problematic social interactions with friends may serve to reinforce this fear and leave these teens wanting to withdraw completely from peers b. Social withdrawal, which at its worst, may become complete social isolation, which has now been shown to have uniquely powerful associations with later psychosocial difficulties and long-term health outcomes into adulthood, ranging from increased risk of loneliness to cardiovascular disease to an increased risk of early mortality. Understanding the risks for the development of withdrawal tendencies into adulthood is necessary. 9. SLIDE #9) Taking a developmental perspective would also warrant some consideration of likely intervening experiences that might mediate the effects of autonomy and relatedness struggles with peers. The link between stress and depressive affect, for example, has previously been found to be mediated by perceived social support in a sample of college freshmen. In middle childhood, friendship quality and quantity has been found to mediate the link between peer acceptance and loneliness and depression. a. But more research is needed on intervening interpersonal experiences in adolescence that could help explain long-terms links between early peer difficulties and later internalizing symptoms. 10. SLIDE #10) So with that, let me turn to our three main research questions a. First we were interested in understanding how a lack of adolescent autonomy and relatedness with their closest peer relates to friendship abilities in late adolescence? b. Secondly, we sought to understand the way in which an inability to establish autonomy and connection within peer relationships relates to two important psychosocial outcomes into young adulthood: depression and social withdrawal. c. And finally, our third goal was to examine potential mechanisms underlying the expected long-term links between lack of autonomy and connection and depression and social withdrawal. I. SLIDE #11) We’ll be examining these questions in a sample of 184 adolescents, drawn from the public school system of Charlottesville, Virginia, who were interviewed and observed in interactions with their closest peers. This larger longitudinal study began assessing teens when they were 13 years old. a. We’ll be reporting results of annual assessments beginning at this first time point at 13, again when teens were 18 years old, and then finally again at age 21 (at which point they are no longer teens, but that term seems to stick in our lab even when they clearly are adults!) b. The sample was evenly divided between males and females c. And is a normative one, so it was representative of the population of the surrounding area in terms of socioeconomics and race. d. The study overall has maintained very low attrition over the course of the now 11 years that it has been running, and generally has over 90% participation at any given time point. 11. SLIDE #12) So to start off, we looked into the relationship between teens’ inability to establish autonomy and connection with peers and friendship competence in late adolescence. 12. SLIDE #13) At age 13, autonomy and relatedness behaviors towards peers were observed during an 8minute videotaped interaction at age 13 in which teens and their freinds were presented with a revealed differences task. This task involved a hypothetical dilemma requiring them each to decide which 7 out of possible 12 fictional characters who are stuck on the planet Mars should be eligible for a place in the one spaceship returning to Earth. After making their decisions separately, they were then brought together to compare their answers, and were asked to come up with a consensus list of seven characters to take back to Earth. The Autonomy-Relatedness Coding System for Peer Interactions was used to code these interactions. a. This scale captures the combination of behaviors that undermine the ability to express autonomy during the disagreement task—for example, avoiding conflict entirely by backing down easily, appearing hesitant to disagree and/or bartering, overpersonalizing the disagreement by blurring the boundary between the person and their position, or pressuring the other person to agree—and behaviors that undermine relatedness with the other person by interrupting or ignoring them, or expressing hostility towards the other person. b. Each 8-minute interaction was reliably coded as the average of scores obtained by two trained graduate student coders blind to other data from the study, and interrater reliability was excellent at .82. 13. SLIDE #14) We then measured close peer reports of the target teens close friendship competence at age 13 and 18 using a scale on the Harter Self Perception Profile for Adolescents, which we modified to be used as a peer report instrument. a. This measure asks the teen’s closest friend to choose between two contrasting descriptors and then rate the extent to which their choice is sort of true or really true about the target teen. b. A sample item includes “Some people don’t have a friend that is close enough to share really personal thoughts and feelings with/some people do have a friend that is close enough to share personal thoughts and feelings with.” 14. SLIDE #15) So what did we find? Not surprisingly, we see that an inability to establish autonomy and connection with close peers predicts relative decreases in close friendship competence in late adolescence. Note that we control for gender and income in this analysis and we used Full Information Maximum Likelihood anaysis, which is true for all subsequent analysis that I will present today. Additionally, the prediction to close friendship competence at 18 from autonomy and relatedness at 13 is significant above and beyond initial levels of close friendship competence at 13. So adolescents who exhibit high levels of behaviors that undermine autonomy and relatedness with friends in early adolescence show relative decreases in their abilities to have solid close friendships at age 18. 15. SLIDE #16) Moving onto our second question, we will examine how an inability to meet the important developmental task of establishing autonomy and connection with friends contributes to depressive symptoms and social withdrawal in young adulthood? 16. SLIDE #17) We use the same measure of autonomy and relatedness in this next set of analyses, and to assess depressive symptoms we first used teens self reports on the Childhood Depression Inventory at 13, and as they moved into young adulthood, we measured depressive symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory. 17. SLIDE #18) To assess social withdrawal at age 13, we used closest peers ratings of teens socially withdrawn behavior on the Pupil Evaluation Inventory. And then again, as adolescents moved into young adulthood, we measured social withdrawal Adult Behavior Checklist. You can see example items on each on the slide here. 18. SLIDE #19) Before moving onto the regression models, I wanted to point out that depressive symptoms and social withdrawal at age 21 are not significantly correlated, demonstrating that these two constructs are quite distinct, and worth pursuing independently of eachother. 19. SLIDE #20) So, onto our findings for depressive symptoms. This first slide is showing you visually what we controlled for. You’ll see we entered gender and income, as well as baseline depressive symptoms at 13, and also baseline levels of social withdrawal at 13 just to make sure that social withdrawal was not perhaps driving this model in any way. 20. SLIDE #21) Our final regression model reveals that an inability to establish autonomy and relatedness with peers during an observed disagreement task at age 13 predicts relative increases in depressive symptoms at age 21. 21. SLIDE #22) Next we tested as similar model for social withdrawal controlling for gender, income, baseline depression levels, and baseline social withdrawal, 22. SLIDE #23) and found that an inability to establish autonomy and relatedness with friends in early adolescence predicts relative increases in social withdrawal at age 21. 23. SLIDE #24) So to quickly recap what we know so far…A failure to meet the developmental challenge of establishing autonomy and connection with peers in early adolescence contributes to increased difficulties maintaining close friendships at age 18, and increased depressive symptoms and socially withdrawn behavior at age 21. 24. SLIDE 25) Now that we have established that there are significant long-term links between a lack of autonomy and connection and later internalizing symptoms and because we already know that a lack of autonomy and connection with peers predicts close friendship competence in late adolescence, we wanted to test whether close friendship competence might mediate the demonstrated long term associations. 25. SLIDE #26) To orient you first to the model, all of these measures have been presented so you should now be familiar with how we assessed these constructs. So we have close friendship competence, lack of autonomy and connection in the observed disagreement task with peers, and depressive symptoms all measured at age 13. We then have close friendship competence and depressive symptoms in the middle boxes measured at age 18, and then again at age 21 situated on the far right of the screen. I’m not going to go through all of the lines in detail, but just know that dotted lines indicate nonsignificant associations, the solid thin grey lines indicate significant predictions that were not part of our main hypotheses, and the bold yellow line in this case is demonstrating the long term link between lack of autonomy and connection and depressive symptoms that was presented previously. 26. SLIDE #27) So we tested the mediation model using the indirect effect option in MPlus, and found that close friendship competence at 18 partially mediated the relationship between lack of autonomy and connection with peers at 13 and depressive symptoms at 21. Although the long-term link remains significant, the total indirect effect from autonomy and connection to depressive symptoms through close friendship competence was significant indicating partial mediation. a. So in other words, a lack of autonomy and connection with peers predicted decreases in close friendship competence at 18 which in turn predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms at age 21. 27. SLIDE #28) We then tested the social withdrawal mediation model in the same way, so you can see from this slide that we’ve now have social withdrawal measured at age 13 indicated on the left and social withdrawal at age 21 indicated on the right hand side. All other constructs in the model are the same as the previous slide, and the yellow line here represents the significant long-term link between lack of autonomy and connection and social withdrawal that we’ve already presented. 28. SLIDE #29) Again using the indirect effect option in Mplus reveals that the indirect effect from a lack of autonomy and connection to social withdrawal through close friendship competence shows a trend towards significance, and you can see that the long term link drops below significance when close friendship is entered into the model. However, given that the indirect effect is not significant, close friendship competence as a mechanism to explain the long term link is less clear. 29. SLIDE #30) Before moving on to our overall conclusions, let me first point out a few limitations. a. First, these data are not experimental so we cannot infer any causal associations with the data presented today. b. Also, It is important to also emphasize that the present study highlighted relational patterns relevant to those teens who struggle with depressive symptoms, but not necessarily with Major Depressive Disorder. Although 48% of the participants showed depressive symptoms in the mild to moderate range at some point during the study, the current sample of adolescents is a community-based sample and was not selected to be particularly at-risk for psychopathology. Therefore, the current results cannot be generalized to major depression as a clinical phenomenon, nor can they be generalized to populations with higher rates of clinically diagnosed difficulties. c. Additionally, while the current study is longitudinal in nature, data were only collected through age 21 and may fail to capture those who develop depressive symptoms and/or social withdrawal later in adulthood. Further research is needed in order to examine if and how early conflict negotiation patterns and later adolescent social functioning difficulties relate to adult depressive symptoms and social withdrawal. 30. SLIDE #31) In conclusion, it should be emphasized that the long-term predictions to young adult depressive symptoms and social withdrawal were made from one, relatively brief observation of teen-peer interactions eight years earlier, highlighting just how relevant critical developmental processes may be for later functioning. a. Additionally, findings suggests the importance of developing autonomy and relatedness skills, even during very minor conflicts, as critical markers of progress toward the development of friendship competence in adolescence. It also suggests there may be some continuity in teens’ early interactions with closest friends that may subsequently prevent them from forming positive, strong relationships with peers in late adolescence. b. Consistent with a stress-generation perspective on depression, Teens who learn maladaptive ways of handling early conflict negotiations may be continually aggravated and stressed within interpersonal relationships, making them prone to later psychosocial difficulties, especially depressive symptoms. Because the observation task used in this study is hypothetical and likely to be of low-stress, the occurrence of negative behaviors toward peers even in such a task suggests that, at least for some adolescents, managing conflict with peers is likely quite challenging and quite meaningful at this stage of development. c. Furthermore, problematic interaction strategies seem to be of primary importance in predicting young adult social withdrawal because they represent an immature and ineffective way of negotiating disagreements within complex relationships—a skill that seems necessary to maintain social connections over time. When these skills are lacking, peers may potentially become frustrated and avoid further social interaction with teens both in late adolescence and early adulthood. 31. SLIDE #32) A partial mediation model for depressive symptoms was supported, though was less clear for social withdrawal. One possible implication of these findings is that if teens who display early conflict negotiation difficulties with friends in the form of failing to assert their autonomy while keeping the relationship intact can learn to be more socially adept in forming close and supportive relationships with peers, they may be able to potentially counteract their risk of developing later psychosocial difficulties. a. Finally, If future research supports the existence of causal links between the constructs examined, then psychological interventions might profitably target dysfunctional conflict negotiation skills and behavioral patterns in early adolescence, as well as social competencies in late adolescence as an approach toward preventing young adult psychosocial difficulties. Helping teens acquire more effective and mature ways of interacting with peers in early and late adolescence, especially during disagreements, and/or teaching teens helpful skills in developing close, social connections may reduce the possibility of these individuals becoming more depressed and socially withdrawn in young adulthood. b. I’d like to acknowledge my co-authors of the study, Joe Allen, Dave Szwedo, and Megan Schad, and to also thank all of my lab member for their help, and the NICHD for the funding to conduct this research. Thank you.