PERFORMATIVE DEBATE

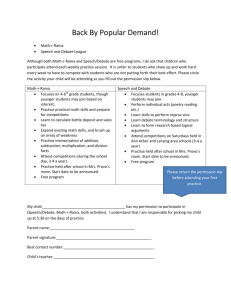

advertisement