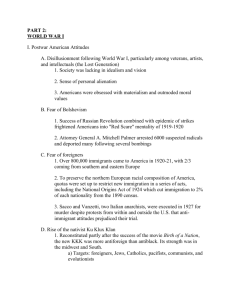

The Scopes Trial The ultimate cause of the Scopes trial was Charles

advertisement

The Scopes Trial The ultimate cause of the Scopes trial was Charles Darwin’s publication in 1859 of On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, helping to touch off a radical revision in the status and content of Christianity. How do you explain the exceptional diversity of living organisms and the history of life in the fossil record? Are organisms separate divine creations, or shifting, fluctuating populations of closely related organisms? Rather than having been created separately by God, could not species have evolved from common ancestors? Virtually every American natural scientist of any repute had come to agree with Darwin that species were mutable and that the fossil record demonstrated the evolution of species from earlier species. Accepting the fact of evolution, however, did not mean that scientists accepted Darwin’s explanation of how evolution worked. For reasons both scientific and theological, Darwin’s theory of natural selection – his proposal that species evolved because the “struggle for survival” made animals with certain traits more likely to survive and reproduce than others – would not find general scientific acceptance until the evolutionary synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s. Many scientists – even some of Darwin’s supporters – produced technical objections to natural selection, questioning, for example, whether small, undirected changes could produce such complex structures as the eyeball. The objections were not merely technical. Many commentators considered natural selection a “moral outrage.” Natural selection seemed to contradict the “argument from design” that had for decades unified theology and natural science. People had been accustomed to viewing the natural world as a revelation of God’s nature and purpose – the elegant “design” of life on earth seemed evidence of an equally elegant “Designer” in heaven above – but Darwin now seemed to be suggesting that nature reveled a God who was either cruel and wasteful or absent altogether. Darwin further undermined the Christian ideal of humanity’s special relationship to God by lumping humans in with all other animals, rather implicitly in Origin of Species and then explicitly in The Descent of Man, published in 1871. Nevertheless, by the turn of the twentieth century, most of the leading Protestant theologians had adapted to the Darwinian environment. They achieved this accommodation both by tailoring their own aspirations to fit the new evolutionary consensus and by adjusting Darwin’s theories to suit them better. Leading Protestant theologians came to argue that religion and science occupied entirely separate spheres. Theology was to give up its former status as arbiter of the natural and supernatural and henceforth confine itself more closely to the arenas of faith and morality. There, beyond the reach of scientific inquiry, religion could survive and perhaps even thrive. Many theologians accepted the fact of organic evolution, but generally threw aside the theory of natural selection. Many claimed that evolution was merely the working out of God’s blueprint for the universe and that natural history revealed clear evidence of organic progress toward perfection. The argument from design – they claimed – still held. This theistic, sanitized version of evolution began to make its way into textbooks and classrooms at the university and secondary levels in the 1880s. Although none of the natural science books around the turn of the century presented a particularly good explication of evolution, almost all of them included the concept. In general, public disputed over evolution seemed to belong to the past. Few observers at the time could have predicted that two decades later, the nation would witness an antievolution crusade popular enough to sponsor forty-one antievolution bills in twenty-one states and powerful enough to suppress teaching of the subject in three states. The fundamentalist movement developed its identity in opposition to modernism – the theological liberals’ effort to reconcile science and faith after the Darwinian revolution. Modernists asserted that the Bible employed symbolic and allegorical language to convey God’s meaning to the ancient chroniclers. Modernists embraced scientific discoveries, including evolution, as part of God’s continuing revelation to his followers, and they felt few qualms about leaving behind the Bible’s literal descriptions of the natural world. Following the literal words of the Bible was less compelling for modernists than uncovering the “spirit and purpose” of Jesus Christ’s moral teachings. At first, the militancy of the fundamentalist spent itself in scattershot crusades, but within a few years, the fundamentalists had united behind the conviction that Darwinian evolution was the one great evil that fed modernism, urbanism, sensationalism, and most of the other transgressions that seemed to be crowding in upon the faithful. Had not Germany’s militarism and “barbarism” grown directly from the belief that a Darwinian “struggle for survival” applied not only to individuals but also to the nations of the world? Had not Social Darwinism, the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak, been the justification to oppose popular social, political, and economic reforms? William Jennings Bryan, three-time Democratic candidate for president, became the mouthpiece of the fundamentalist cause against evolution when he joined the prosecution at the Scopes Trial. Bryan believed that evolution and scientific education were weakening Christian belief. Evolution had now replaced modernism as the fundamentalists’ central concern, and the battleground shifted from denominations to the public schools. Tennessee had recently passed the Butler Act, which made it a crime to teach “any theory that denies the story of the Divine creation of man as taught in the Bible.” The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) wanted to test this law. The ACLU’s advertisement produced a response in the small town of Dayton, Tennessee, a town looking for a little publicity. Dayton “boosters” asked a young general science teacher named John Scopes if he was willing to stand for a friendly trial. Although it is not clear that Scopes had ever taught about evolution, he was willing to admit that he had for the purposes of the case. Scopes “confessed” and was duly arrested under the Butler law. Meanwhile, Dayton contacted the ACLU and the newspapers. (The ACLU needed Scopes to lose in order to be able to appeal the case to a higher court.) Largely in response to Bryan joining the prosecution team, Clarence Darrow, nationally renowned defense attorney who just saved two killers from the electric chair, joined the defense team. Known as the “monkey trial,” a term coined by H.L. Mencken, the Scopes trial became the original “trial of the century.”