William Darby & Jessica McDivitt

advertisement

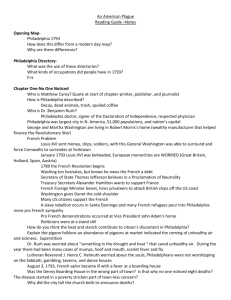

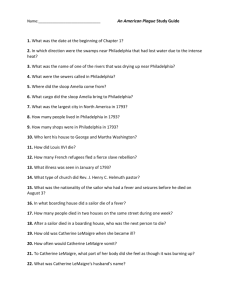

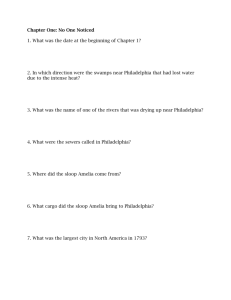

Teacher’s Note: In Unit One, students in grade seven read the non-fiction text, An American Plague which discusses the yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia that occurred in 1793. Students analyzed text in order to identify how the social, political, economic and religious aspects affected the citizens of Philadelphia in 1793. Mrs. Kidd & Ms. Woestman Assessment Question Construct a museum display card that summarizes two central ideas in An American Plague. William Darby In An American Plague, there are several central ideas that are a constant in the book. Two of them are that the doctors are trying to find cures and causes for the Yellow Fever and the government is dealing with the sick and homeless. The central idea of doctors finding cures and causes is present in all chapters of the book. In chapters one to three, doctors are suspecting yellow fever, but are not sure. However, doctors are sure a deadly fever is ravaging through Philadelphia. In chapters four through six, there are two major cures available. Dr. Rush’s “ten and ten” in which the body is heavily bled and purged where the body is poisoned in order to vomit and have diarrhea. The other cure is Dr. Deveze’s cure, mild bleeding, liquids, and rest. In chapters 7 through 9, the two previous cures start losing effect. The only thing stopping the fever is cool weather. At one point, Bush Hill mansion is used as a hospital for the sick (it was taken over by the city in 1793) hoisted a white flag, “No more sick persons here!” But then, as people returned to the city, they fell ill and the flag was lowered. In chapters ten and eleven, doctors started to consider mosquitoes as the transmitters of the yellow fever. Once doctors proved this, around 1910, breeding grounds for the mosquito were destroyed, and pesticides were used to wipe out mosquitoes in certain areas. Another central idea is that the government was dealing with the sick and homeless. In the first three chapters of the book, up to thirty people every day. There was still some room at hospitals. Then, in chapters four through six, the hospitals ran out of room, so a new one was “made.” At Rickett’s Circus, where the circus came, the sick were held in horrible conditions. No volunteers were there to help them, so they all lay begging for water, moaning with pity, and vomiting on each other. Then, the neighbors got tired of the unsightly place and burned it down. The next make-shift hospital was William Hamilton’s mansion at the time he was in Britain. Four doctors were made responsible for Bush Hill, but the disease immobilized two, and out an end to the others. In chapters seven to nine, Bush Hill was put under new management. Peter Helm and Stephen Girard turned Bush Hill into “a pocket of calm and hope,” where patients were always taken care of and in good conditions. In chapters ten to eleven, people all over the world die of yellow fever, until 1793, a safe vaccine is made and anti-mosquito campaigns begin to take place in the early 1900s. As you can see, the two central ideas of doctors finding cures and causes and the government dealing with the sick are both eminent throughout the book An American Plague. Jessica McDivitt One of the important individuals who helped fever victims was Matthew Clarkson, the mayor of Philadelphia in 1793. Clarkson was much more of a symbolic head of the town, “real” power was given to other individuals. However, when several government officials were to leave, Clarkson suddenly found the reigns of the city in his hands. Instead of running away from this looming responsibility, Clarkson embraced it. He took several measures to improve the overall health of the city. First was a meeting with the College of Physicians in order to be counseled by them. He then formed a committee made of enlightened individuals who helped volunteer their service throughout the epidemic. The committee cleaned streets, dug and filled mass graves, turned Bush Hill into a decent hospital where many stricken were properly treated and did several other things to keep Philadelphia in working order. Without mayor Clarkson’s ideas and motives, Philadelphia in 1793 would have been less clean and many of those stricken by the fever would have perished without proper care. Other influential individuals in the epidemic were members of the College of Physicians who stayed in Philadelphia and other doctors who treated victims of Philadelphia. They believed that it was their duty to discover a cure for the plague and to treat sick patients. However, when Clarkson called together a meeting with the College of Physicians, the members argued about many things concerning the fever. These arguments and beliefs continued to show throughout the epidemic. Seemingly during the fever, the physicians found their pride to be more important than their unity.