(Word, 448 KB)

advertisement

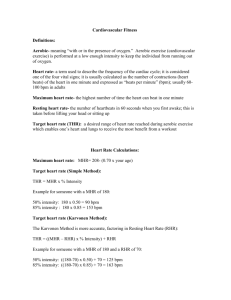

Exercise Move your body to build your brain © 2014 Commonwealth of Australia through the Australian Government Department of Education. This material may be used, reproduced in material form and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes until 31 December 2018, provided all copyright notices and acknowledgements are retained. Why are executive functions important? Exercise is the single most effective way to boost brain overall function, which in turn boosts executive function. It's not just any old exercise either: the benefits come from moderate to high-intensity aerobic exercise, especially when combined with complex motor movements such as dance or martial arts. If you were to take action on only one piece of advice from The Adventures of You, it should be this one: get moving! This resource sheet is for personal use and for those parents, teachers and carers who want to help boost their child's brain function. It explains the cognitive benefits of exercise, how it works (roughly) and the kinds of things that encourage the best results. Build your brain: cognitive benefits of exercise Exercise benefits all aspects of a person's life as it: improves alertness, attention and motivation encourages nerve cells to bind to one another stimulates the development of new nerve cells. Here's how it works When you work your heart and lungs, they push blood and oxygen throughout your body and brain with a number of positive effects. A host of chemicals including serotonin, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), norepinephrine and dopamine are produced. These hormones and other molecules make you feel calm, patient, focused, positive and optimistic – like you can handle anything. You burn fat which helps produce the insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) that is critical in the formation of new cells. And you want your brain to have new cells, because in biology there is no standing still. Brain cells are either growing or dying, so you want them to be growing. As your exercise increases in intensity, your body begins to burn glucose and your muscles begin to develop micro tears. Your body responds as if there is an emergency which is why, if you're unfit and you jump into exercise, you start to feel panicked – your body is quite literally having a panic attack. Your muscles release even more growth hormones to make more blood vessels, and your brain produces a host of proteins and enzymes that sweep up all the waste molecules being produced. This process leaves the brain cleaner, and better connected. © 2014 Commonwealth of Australia through the Australian Government Department of Education. This material may be used, reproduced in material form and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes until 31 December 2018, provided all copyright notices and acknowledgements are retained. 2 How do we get the best results from exercise? The short answer The short answer is to get outside and walk, jog, run or sprint on a regular basis. You want to do mid-level of exertion, working 'somewhat hard'. If you did that every second day, great. If you did it every day, even better. However, the higher the intensity the more you will need time to recover. The ideal is to mix up all these levels of intensity: walking or jogging every day, running a couple of times a week, and every now and then throwing in some sprints. Different benefits come from each level of intensity, and softer days give time to recover from harder ones. The more precise answer If you want to apply a little more precision, use your maximum heart rate (MHR) as a guide. Table 1: The relationship between level of exercise and maximum heart rate (MHR) Level of exercise % MHR Low intensity 55–65% Medium intensity 65–75% High intensity 75–90% To calculate your MHR, simply deduct your age from 220, for example, 220 – 21 years old = 199 beats per minute. This is only a rule of thumb, but it is accurate enough for general use. If you then work out ranges for low, medium and high intensity exercise using the table above, you will have a good set of targets. Keeping track of your heart rate Research shows that use of feedback devices such as a pedometer or heart rate monitor greatly increases the effectiveness and consistency of exercise. Heart rate monitors are commonly available from sports stores, and consist of a chest strap sensor and a digital watch display. Whenever you exercise you simply enter the target heart rate for the session, and then adjust your pace based on feedback from the watch. Judging how much time This is one of those things where anything is better than nothing, but more is better. A good target is 45–60 minutes per day but if you find that overwhelming ignore it. The important thing is to start somewhere and just stick with it. © 2014 Commonwealth of Australia through the Australian Government Department of Education. This material may be used, reproduced in material form and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes until 31 December 2018, provided all copyright notices and acknowledgements are retained. 3 Mixing social engagement with exercise Here are a few reasons why it's good to have social engagement in your exercise. Increases mental effort Exercise or sports that involve coordinating with other players or partners is inherently more difficult and unpredictable. Greater demands are placed on your precision, attention and mental flexibility, and this increases the overall benefit of the exercise. Partnered dance, tennis, martial arts, netball, AFL, basketball – these are all good examples of sports with in-built social complexity. Sustains motivation Exercising with others can help reinforce a routine, build motivation and prevent boredom. Cycling, rowing and running are often done with partners simply to help make the activity more fun and engaging. Develops social skills Group activities are excellent ways to develop social skills, not just the baseline skills such as planning, sharing and cooperating, but also the higher order skills such as having a conversation and getting a date. Organisers can build rules into an exercise routine to help target this, for instance saying that everyone in a team has to discover certain pieces of information about each of their team members or partners. To make it even more difficult, a team member is not allowed to ask for the information directly. Limitation of contact sports Contact sport does not help executive function, and if anything may reduce it. That's not to say: don't play contact sports. It is just that if your goal is to improve executive function then you need to spend time on other forms of exercise. Benefits The right kind of exercise regulates all the neurological systems related to mood, in particular those associated with fight or flight responses, happiness or depression. In terms of stress and anxiety, exercise forces the issue by putting you in a stressful situation where your heart rate is elevated. By continuing to exercise in this aroused state you cue your nervous system to recalibrate its sense of what is normal and what is not. The long-term effect is that you are less likely to get panicked or angry about things because your nervous system is more used to dealing with stressors. In the case of depression, exercise forces the production of dopamine and stimulates the entire system associated with pleasure and elevated mood. Like a muscle, this system improves with use, and it lifts baseline mood as it develops. © 2014 Commonwealth of Australia through the Australian Government Department of Education. This material may be used, reproduced in material form and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes until 31 December 2018, provided all copyright notices and acknowledgements are retained. 4 Ways to maintain exercise Sticking with it Exercise can be hard to start and easy to stop. Here are a few simple tactics to help you stick with it. Create a routine Do it in a group Use iPods Automate the exercise part of your life by following a strict routine, for example starting every morning with a run or exercising through that midafternoon slump. Social engagement and commitment can be enough to keep you going. Not likely to work with introverts, unless the exercise is inherently stimulating like dance or football. If the exercise has a low mental load, then it's a great excuse to listen to music, books or podcasts, or watch TV. Scheduling Frequency and routine are the most important things. It's also worth noting that brain function is elevated in the hour or so immediately after intense exercise. So the ideal routine is probably 45–60 minutes of complex aerobic activity every morning, followed by the hardest task of the day. Teacher tip Tell your students to run before they take an exam or have to solve a complex problem! I hate exercise! If you really hate exercise, then this whole resource might seem like bad news. There are a couple of things we can say. The first is that you may have a genetic predisposition towards not liking exercise. For instance, if you have a genetic makeup that doesn't produce dopamine as effectively as other people, then you are likely to find exercise unrewarding and not want to continue with it. But the fact is that exercise can, over time, compensate for your genetic makeup. In the case of dopamine deficiency, exercise boosts production not only of dopamine, but also dopamine receptors, creating a virtuous cycle over time. The other reason why you might hate exercise is because you are already deeply out of shape. Yes, you are going to find it hard to get started. But the good news is that even the smallest steps create benefits that will compound over time. No matter how poor your condition, the best thing you can do for yourself is get out and start walking every day. Put on your headphones. Listen to something. Walk as fast and far as you can. You'll enjoy it, and eventually your conditioning will improve so you can take on more advanced exercise. © 2014 Commonwealth of Australia through the Australian Government Department of Education. This material may be used, reproduced in material form and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes until 31 December 2018, provided all copyright notices and acknowledgements are retained. 5 Ideal aims 45–60 minutes every day Elevated heart rate Mentally challenging Socially engaging Resources Supporting worksheets available on the myfuture website Exercise planner Exercise chooser Books The best overall account of the relationship between exercise and mental functioning is Spark: the revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain by John Ratey and Eric Hagerman, 2008. Sources of information Best, JR 2010, 'Effects of physical activity on children's executive function: contributions of experimental research on aerobic exercise', Dev. Rev. 30:331–551 Davis, CL, Tomporowski, PD, McDowell, JE, Austin, BP, Miller, PH et al. 2011. 'Exercise improves executive function and achievement and alters brain activation in overweight children: a randomized, controlled trial', Health Psychol. 30:91–98 Diamond, A 2012, 'Activities and programs that improve children's executive functions', Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 335–341 Erickson, KL & Kramer, AF 2009. Aerobic exercise effects on cognitive and neural plasticity in older adults. Br. J. Sports Med. 43:22–24 Hillman, CH, Erickson, KI & Kramer, AF 2008, 'Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition', Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9:58–65 Lakes, KD, Hoyt, WT 2004, 'Promoting self-regulation through school-based martial arts training', Appl. Dev Psychol. 25:283–302 Ratey, JJ & Hagerman, E 2008, Spark: the revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain, Little, Brown, New York Voss MW, Nagamatsu LS, Liu-Ambrose T & Kramer AF 2011, 'Exercise, brain, and cognition across the lifespan', J. Appl. Physiol. 111:1505–13 © 2014 Commonwealth of Australia through the Australian Government Department of Education. This material may be used, reproduced in material form and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes until 31 December 2018, provided all copyright notices and acknowledgements are retained. 6