Search Committee - Compiled Sections2

advertisement

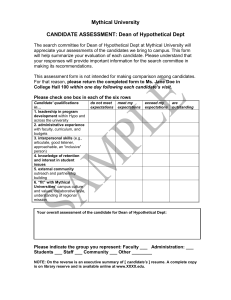

Lessons Learned by a Standing Search Committee Developing Better Practices Charles L. Gilreath Christine L. Foster Leslie J. Reynolds Sandra L. Tucker Texas A&M University Libraries College Station, TX 77843-5000 Sandra L. Tucker, corresponding author s-tucker@tamu.edu Submitted to Journal of Academic Librarianship December 2008 Abstract This paper describes the reasons for establishing a standing committee for faculty searches at Texas A&M University Libraries, the committee’s practices as they have evolved over time, and the successes the committee has achieved in reducing the length of searches, minimizing staff time, improving job announcements and scoring rubrics, and enhancing the interview experience for job candidates. Introduction In his 1995 study The Age Demographics of Academic Librarians: A Profession Apart, Stanley Wilder projected that by 2010 just under half of librarians working in leading research libraries would be over 50 years old, with the single largest cohort aged 54-59 and contemplating retirement.1 This demographic fact of life, coupled with normal job mobility common among younger professionals and the continuing need for libraries to adapt to changing research and teaching environments, makes professional staff recruitment a high priority for library administrators. With libraries often conducting multiple searches for professional positions each year, managing the recruitment process and controlling the costs in staff time is a challenge. Texas A&M University, like its sister institutions, has continually faced the need to recruit for several professional positions each year. Each of these recruitments entailed creation, training, and oversight of a search committee comprising from five to seven individuals. Often several searches were active at the same time, demanding time and attention from a very high percentage of the library faculty and staff, and often resulting in considerable scheduling complications. Professional searches were often marked by inefficiencies and frustrations for all involved in the process. Frequently, searches were taking many months to complete, and because of the delays the Libraries often lost very good candidates from the pools. In response 1 to this environment, in 2007 the Dean of Libraries appointed a new standing search committee with a charge to shorten the time-to-hire, to rationalize the search process generally, and to conduct all professional searches. Literature Review Professional recruitment is a topic appearing regularly in the literature. Most of the key articles either critique existing recruitment practices and/or provide general guidance for structuring and conducting professional searches. William Fietzer’s 1993 article provides a good review of recruitment practices in libraries, criticizes the ineffectiveness of the processes then common, and recommends better and more widespread training of library staff in search and interview skills.2 Four years later John Lehner critiques the selection process further, focusing particularly on the need to improve the alignment of candidate skills with well understood position requirements.3 He points out that onsite interviews, in particular, need to provide for ample opportunities both to familiarize candidates with the organization, the job, and potential colleagues and to allow the organization to make an adequate analysis of the candidate’s skills for the position. In 2004 ACRL’s Committee on the Status of Academic Librarians updated their guidelines for search committees to use in screening and appointment of librarians, detailing best practices for academic libraries to follow when conducting searches.4 Wheeler, Johnson, and Manion updated and expanded guidance on the search process in 2008.5 Writing from the perspective of professional recruiting for an academic law library, they reviewed best practices for search committees, including topics not frequently discussed in other articles such as courtesy interviews, meal functions for candidates, and orchestrating a workable interview schedule. These articles, as does most of the literature on the subject, focus on the process for conducting a single search, and in most cases the environment discussed is one in which a new 2 search committee is created for each search being conducted. Less emphasis is placed on searchcommittee dynamics and effectiveness or on issues surrounding the pressures of trying to fill multiple vacancies in a short time period. Recent articles by Howze and Munde address some of these issues.6,7 Howze, reporting on the work surrounding a search with an unusually large pool of applicants for a single entry-level position, discusses factors related to the effectiveness of the search committee in narrowing a 125-person applicant pool to ensure that the best qualified candidates were successfully identified. He discusses issues such as the difficulty of scoring paper applications for desired qualifications as well as potential influences of varying resume formats on search committee assessments. Munde focuses on the problem of multiple vacancies in her article, which reports on a survey of ten library directors whose libraries conducted at least three professional searches in 2006. She reports on strategies employed in these libraries for dealing with the vacancies, for reassessing organizational needs for defining new positions, and for expediting searches and hires. Committee Formation and Charge Following several semesters in which the Texas A&M University Libraries experienced multiple vacancies, with many of the recruitments resulting in failed searches, the dean reviewed the library’s search process and decided to embark on a different approach by establishing a common search committee. This approach is one that had been used successfully by some of the academic departments on the campus. The committee’s charge is to manage professional searches from the point that a position is approved by the dean for recruitment through onsite interviewing. The initial committee comprised three tenured faculty members, a classified staff member, a non-faculty professional, the Libraries’ Associate Dean for Faculty Services, and 3 Executive Associate Dean (chair). Support for the work of the committee was provided by the Associate Dean for Faculty Services and the Libraries’ Personnel Office. Initial appointments were for two years, giving the members of the committee two full academic years to develop and refine committee processes and workflows. At the end of the initial two years, members would draw lots to establish a staggered replacement rotation that would bring new members onto the committee each year to serve two-year terms. Scheduling From the beginning the committee blocked a standing meeting of one-and-one-half hours per week. Because of the workload few meetings have been canceled. In two years of functioning, the committee has typically been managing from two to four searches at a time. An important task has been to develop a timeline for all the active searches. Staggering them has been necessary to allow the committee to manage its time and manage the impact of interviews on the larger organization. Each search involves developing the position description and announcement, advertising, reviewing applications, conducting telephone interviews, scheduling onsite interviews, meeting with the candidates, doing reference checks, and making an offer. Considering, first, when the onsite interviews should occur, the committee proposes a deadline for initial review of applications, and then counts back to determine when advertising must begin. The process encourages discipline and efficiency. A related factor is determining desired start dates for new employees. Librarians at Texas A&M are on the tenure track, and the tenure clock begins September 1 for anyone hired in a given calendar year. To allow them sufficient time for success, it is desirable for incoming assistant professors to start well before September 1. 4 Developing the Position Description, Rubric, Announcement When a faculty position is approved by the Dean, the hiring supervisor develops and/or updates the position description and a draft announcement and submits them to the standing search committee. Individually, the committee members review the documents and then meet as a team with the hiring supervisor to clarify any questions about the position responsibilities and the supervisor’s wishes regarding skills and traits. Each search committee member strives to understand what is required to fulfill the job and assess what required and desired qualifications would most benefit the organization. If portions of the the position announcement seem inconsistent or ambiguous, the search team assists the supervisor in modifying the text, while ensuring that the qualifications most important to the hiring supervisor remain. When the committee and the hiring supervisor are satisfied with the position announcement, they move on to creating the scoring rubric that will be used to rank the applicants who meet the minimum required qualifications. The rubric is a list of the required and desired qualifications with points assigned for the knowledge, experience, and personality traits that can be documented in the application. There are gradations to distinguish a more-qualified from a less-qualified applicant. Someone with five years experience, for example, might receive more points than someone with two years experience. Someone who had chaired a national committee might receive more points than someone who had been a member. Each factor in the rubric is assigned a multiplier according to its relative importance in the eyes of the hiring supervisor. One manager might value a particular academic background while another might be looking for teaching experience. The goal is to assign more weight to the more important factors when scoring the applications. 5 The committee reviews the position announcement against the rubric to make certain that the rubric covers everything desired and that the announcement includes all qualifications to be scored. If a particular qualification is not mentioned in the position announcement, points cannot be assigned for it. When the search committee and hiring supervisor have reached mutual agreement on the type of person needed to fill the position and are satisfied with the position announcement and rubric, the search committee forwards the documents to the Personnel Office. Personnel reviews the position announcement to ensure consistency with institutional guidelines and regulations, posts the documents in a shared online folder for committee use, and distributes the announcement as described further below. With experience the search committee has improved its skill at writing announcements and developing rubrics and has learned a number of lessons about managing its processes. Among them are the following: Date all drafts of documents. They are likely to go through several iterations before completion. Spend as much time as needed with the hiring supervisor to reach a common understanding of the position description and desired qualifications. Complete the scoring rubric before fine-tuning the position announcement to ensure that all desired qualifications are mentioned in the announcement. Incorporate the details of the rubric into the spreadsheet used for scoring applications so that committee members can refer to a single document while scoring applications. Another lesson was to recycle the best rubrics and announcements. After about six months the committee realized that some rubrics worked better than others at describing desired 6 qualifications. During debriefings after searches, members sometimes wished that they had been able to give points to a candidate with a certain kind of experience that was not part of the rubric; new factors were added to later rubrics as a result. As discussions led to refinements, the committee developed a useful collection of rubrics that it could apply over time to any number of positions. Likewise, the committee began saving and reusing effective phrasing in position announcements. The various hiring supervisors all contributed insights that improved the announcements that appeared subsequent to the announcement for their position. The best phrases, sentences and paragraphs for position descriptions, announcements, and rubrics are retained in a shared folder for search committee use. Distributing the Position Announcement and Receiving Applications The Personnel Office plays a vital role in the search process, first reviewing the announcement for compliance with guidelines and then distributing it to appropriate publications, websites and email lists. The office becomes the point of contact for applicants, answering questions related to the vacant position. It also serves the search committee by maintaining files and tracking processes and deadline dates. The committee has approved a standard list of places to which the Personnel Office sends all announcements. The committee and the hiring supervisor may request additional postings to email lists or websites intended to reach individuals with particular qualifications, a catalogers’ list for a cataloging position, for example. Personnel maintains a log in the committee’s shared folder of where and when the announcement has been posted. While the Personnel Office bears the primary responsibility for distributing the announcement, the committee also encourages library faculty to post directly to email lists that 7 accept position announcements and provides them with approved text. Although it is not comprehensive, the committee attempts to maintain a list of the lists for future consideration. Over time, the committee discovered that online announcements yielded more applications than print announcements, and as a result, investigated and purchased online advertisements at bulk rates from the Chronicle of Higher Education. One lesson learned was that formatting of the advertisement is critical. The committee now previews the ads to ensure that they are presented effectively. Because so many of the applicants are not U.S. citizens, the committee does ensure that all positions are posted to at least one national print source such as American Libraries or the Chronicle of Higher Education. Such a posting is critical in case the person hired needs institutional sponsorship to obtain a work visa or permanent residency. Another enhancement to the announcement and advertising process was the creation of a web page to direct applicants to information about the university and its services, housing, and the community. The committee includes a link to the web page in position announcements. The committee accepts applications via mail, fax, or email. The Personnel Office adds the names of the applicants to the spreadsheet, called the matrix, that includes the scoring factors. A Personnel employee scans the print applications, posts an electronic copy of all applications to an online folder, and notifies the committee that the applications are available for review. Scoring Applications Committee members print copies of the applications from the online folder and then read and score them individually, according to the rubric described above. This task may involve several hours of work, depending on the number of applications. 8 Committee members enter their scores into a spreadsheet, called the matrix, that weights the scores as determined by the rubric. The committee learned early that it was not an effective use of its time to read scores aloud and tabulate them as a group. Instead, a Personnel employee combines the individual matrixes of the committee members into a single matrix that shows both the combined scores and the individual scores of committee members. Some committee members tend to score higher than others do, but, generally, the relative ranking of the applicants has proved to be consistent. When the matrix includes an outlier number, the individual scorer will generally double-check and explain the anomaly. During review of the combined matrix the committee looks for breaks between clusters of scores. Based on the clusters, the committee decides which candidates to interview by telephone and which additional candidates, if any, to keep in the pool. The committee then shares the applications of the candidates still in the pool with the hiring supervisor and adjusts the list or the number to be interviewed by telephone, based on discussion and consensus. Together the committee and the hiring supervisor develop a set of questions for the telephone interview that will elicit further information on the required and desired qualifications. Telephone Interviews Once the initial pool has been cut in consultation with the hiring supervisor, the committee notifies the Personnel Office so that they can contact both applicants no longer under consideration and “second tier” applicants who did not make the first cut but who are still in the pool. The Associate Dean for Faculty Services contacts in person any internal candidates who are either second tier or are being dropped from the pool. Committee members divide the remaining pool for telephone interviews, with two members of the committee participating in each of the interviews. A member of each interview 9 team contacts applicants to schedule a time for the interviews, which typically last no more than a half hour. The telephone-interview teams use a common script consisting of a brief description of the position, a half dozen or so questions to the candidates, an opportunity for the candidates to ask questions, and information about the position and the search process. The telephone interviews are structured to gain some specific information about a candidate’s knowledge, but the larger goal of the conversations is to help committee members gauge the individual’s interpersonal and verbal communications skills. The two-person interview format was chosen as an additional means of ensuring fair judgment of those latter skills. A copy of the responses to each telephone interview is then distributed to the entire committee, and after all interviews are completed, the committee then discusses the active pool in light of the knowledge gained through this part of the process and makes a report to the dean with recommendations for whom to invite to the campus for on-site interviews. Candidates who are not being invited for a campus interview are notified by the Associate Dean for Faculty Services. Campus Interviews – Before and During When the search committee and the hiring supervisor have agreed on which candidates they would like to bring to campus for an interview, the committee chair reviews the list with the Dean for her approval. Because the Dean prefers to meet with all job candidates, the Personnel Office checks her schedule before interview dates are set. The search committee and the hiring supervisor collaborate to frame a presentation topic and to determine the groups and individuals with whom the candidate should meet. In general, the presentation topic relates to the position but is broad enough to allow the candidate 10 considerable latitude in determining what to cover. Recent examples include “Outreach to Science and Engineering Faculty and Students in the Electronic Age” and “Current Issues and Trends Affecting Cataloging in Academic Libraries.” The committee asks the candidate to speak 10-20 minutes to allow time afterwards for interaction with the audience. After the interview topic and available dates have been determined, the Personnel Office contacts the candidates to communicate the Libraries’ interest and to negotiate firm dates for the visit. A Personnel employee explains the general procedure for the interview and communicates the presentation topic and length. She also reserves a hotel room, makes reservations for air travel, and emails the final interview schedule to the candidate. A typical interview schedule includes the following elements: A member of the search committee meets the candidate at the airport in College Station and drives the candidate to the hotel. The search committee member has generally contacted the candidate in advance by email to explain how to spot him or her in the small crowd at the airport. The same search committee member picks up the candidate at the hotel for a community tour – generally about an hour and a half before the dinner reservation, earlier in the day when daylight hours are short. Personnel or the search committee member has asked the candidate in advance whether there is a preference for apartments or single-family housing. The tour is informal, and the route is determined by the search committee member who may provide a map, an apartment guide, and materials from the Chamber of Commerce. The tour guide and the candidate are joined by one or two additional librarians for dinner, usually the hiring supervisor and/or members of the search committee. The 11 committee generally selects the venue from among locally-owned restaurants to offer local color, favoring venues that are quiet and conducive to conversation. Dinner is viewed as an opportunity for social interaction – to answer the candidate’s questions about the university and the community and to learn more about the candidate’s interests and experiences. On the morning of the interview a committee member picks up the candidate at the hotel and provides a brief tour of the library as he/she is escorting the candidate to the room for the presentation; the presentation is generally scheduled first to relieve the candidate of worrying about it during the rest of the day. The interview schedule and a copy of the candidate’s application have been emailed in advance to everyone in the Libraries. All are invited to the presentation. Following the presentation, audience members may ask the candidate questions about the presentation or about his/her education and experience. If time permits, the candidate is invited to ask questions of the audience. Personnel provides periodic employee education on the topic of appropriate questions. If more than a few months have elapsed since the last interview, it is time for a review of interview protocol. The candidate meets with groups of individuals with whom he or she will interact on the job – members of the same department and members of other departments who are considered to be stakeholders. A librarian for electronic resources, for example, might meet with public services librarians who have responsibilities for collection development. Some departments work with a pre-determined set of questions to keep the conversation rolling and to be sure to cover the same ground with every candidate. 12 Depending on the composition of the group, a member of the search committee may attend to ensure appropriate questioning. The candidate meets with the Committee on Appointment, Promotion, and Tenure, which explains the policies and procedures surrounding the faculty status accorded librarians at Texas A&M and answers the candidate’s questions. The candidate meets individually with the hiring supervisor, who may explain the department’s responsibilities and the criteria used in faculty evaluations; with the Associate Dean for Faculty Services, who explains university benefits and the Libraries’ start-up package; and with the Dean and the appropriate Associate Dean, who provide a high-level view of the Libraries’ mission and goals and ask their own questions about the candidate’s qualifications. At the end of the day the candidate meets with the full Search Committee, which asks a set of questions intended to elicit information about the candidate’s communication style, leadership style, and approach to work. The committee does its best to put the candidate at ease and offers another opportunity to ask questions. To conclude, the committee asks if the candidate is still interested and whether it’s okay to contact references and explains the anticipated timeline for decision making. In the year and a half it has been in existence, the committee has fine-tuned its procedures for the on-site interview, based on lessons learned. Recommended practices now include the following: 13 Provide the candidate with information about the university and the community in advance of his or her visit through a web page with links to appropriate resources and by mailing a packet of print materials. Schedule the candidate to meet with recently-hired librarians to discuss what it’s like to be new to the community and the Libraries. Send calendar appointments to all involved in individual and small-group meetings and to everyone for the presentation. Have lunch catered at the library to save the time that might be spent on traveling to a restaurant on the interview day. Supply name tags for some small-group meetings. The feedback the committee has received from candidates regarding their interview experience consistently mentions the courtesy and friendliness of all they’ve met, the professional tone of the interview, and the opportunities and resources available to new librarians. The committee believes the positive impressions can enhance the reputation of the Libraries over the long run. Post-interview Process The committee invites feedback about the candidate from all library employees - those who participated in meetings with the candidate during the interview process as well as those who wish to evaluate just the resume and cover letter. A Personnel employee hands out feedback forms at the presentation, and the form is posted on the intranet. The forms may be returned, signed or anonymous, to any committee member. Some employees choose to send to send their comments via email to one or all committee members. Additionally, the Committee on Promotion and Tenure comments on the candidate’s understanding and potential ability to 14 meet the scholarly requirements of the position and recommends what academic rank and tenure standing to offer. Together the committee and the hiring supervisor review all the feedback to determine if there is consensus on strengths and weaknesses and to look for comments that provide additional insight into the potential success of the candidate at Texas A&M University Libraries. If the hiring supervisor deems the candidate still viable, then committee members contact references for additional background information. Reference checks are conducted by telephone, using a standard script of mostly openended questions. Additional questions may be asked of references regarding issues detected during the interview. Together with the hiring supervisor the committee reviews the results of the reference checks. The committee chair compiles an executive summary for the Dean concerning each candidate that covers the feedback forms, notes from reference checks, and the assessment of the committee as to whether or not the candidate is considered acceptable for the position. At this point the committee’s job is complete, and members send all notes and paperwork to the Associate Dean for Faculty Services for filing or disposal. The Dean decides to whom to offer the position, as well as the initial salary offer, and rank. The Associate Dean for Faculty Services extends a verbal offer. If the candidate was recommended for a rank above Assistant Professor, the candidate is told that it is pending approval from the Libraries’ faculty and the Board of Regents. After the offer is extended, the Libraries’ tenured faculty at that rank and above (if applicable) will vote on the acceptability of bringing in the candidate at the higher level with tenure. If the candidate indicates that the offer will be accepted, a written offer is extended. Lessons Learned and Conclusion 15 By establishing a standing faculty search committee, Texas A&M University Libraries has markedly improved its searches for new faculty. The average time from vacancy to hire has been reduced. The learning and start-up time for new committees has been eliminated. Processes are polished, resulting in a positive experience for applicants. The committee spends a considerable amount of time up front with the hiring supervisor, ensuring that the position description, announcement, and scoring rubric are easily understood, rational, and match required and desired qualifications. Timelines for all active searches are set at the beginning to stagger the interviews and avoid conflict with conferences, holidays, or other local conflicts such as home football games. Although recruiting begins with the hiring supervisor and the search committee, all library faculty and staff are given opportunities to participate in the interview process. Employees who help to recruit through their interactions with candidates and provide the committee with valuable feedback feel that they have a stake in helping new hires to succeed. Facilitating employee involvement is a committee priority and has led to steps such as sending appointments for candidate sessions, emailing cover letters and resumes to everyone in advance of interviews, and providing structured feedback forms. The overall goal is to hire the best candidate for the job while making the best use of scarce human resources in the recruitment process. To date the committee has been pleased with its applicant pools and very pleased with the quality of the Libraries’ new hires. Bibliography 16 1. Stanley Wilder, The Age Demographics of Academic Librarians: A Profession Apart, (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1995), p. 41. 2. William Fietzer, “World Enough, and Time: Using Search and Screen Committees to Select Personnel in Academic Libraries,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 19 (July 1993): 149-153. 3. John Lehner, “Reconsidering the Personnel Selection Practices of Academic Libraries,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 23 (May 1997): 199-204. 4. Association of College and Research Libraries, Committee on the Status of Academic Librarians. “A Guideline for the Screening and Appointment of Academic Librarians Using a Search Committee,” C&RL News 65 (April 2004): 220-21. 5. Ronald E. Wheeler, Nancy P. Johnson, and Terrance K. Manion, “Choosing the Top Candidate: Best Practices in Academic Law Library Hiring,” Law Library Journal 100 (Winter 2008): 117-135. 6. Philip C. Howze, “Search Committee Effectiveness in Determining a Finalist Pool: A Case Study,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 34 (July 2008): 340-353. 7. Gail Munde, “Managing Multiple Vacancies: Ten Library Directors’ Suggestions for Expediting Multiple Searches and Mitigating the Effects on Staff,” Journal of Academic Librarianship 34 (March 2008): 153-159. 17