Benefiting from MOOC

advertisement

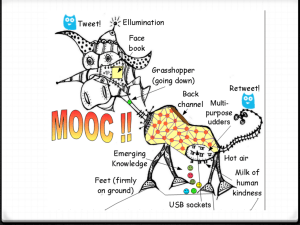

Benefiting from MOOC Youdan Dai Zhang Learning and Teaching Centre British Columbia Institute of Technology youdan_zhang@bcit.ca Abstract: The development of MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) has attracted public attention since 2012 by setting its goal to provide high quality education at low cost. This paper explores some ways of integrating existing MOOCs into post-secondary curricula from an instructional designer’s perspective, and discusses the curriculum and instructional design supports needed to benefit from the educational innovation. Existing MOOCs could be integrated in post-secondary curricula in several ways: 1) Using MOOC components as learning objects; 2) Flipping classroom with MOOCs; 3) Developing challenge courses for MOOCs; 4) Transferring credits from MOOCs; 5) Providing learner services to MOOC participants. Introduction The idea of MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) has attracted public attention since 2012, when universities such as Harvard and MIT, started developing and delivering MOOCs. The innovation carries the hope of giving access to high quality education for free or at a very low cost. At the beginning of 2013, major MOOC providers have developed more than 250 free online courses, and the number is increasing. While those elite universities could invest in MOOC for reputation and revenue, the second or third tier institutions may join the adventure to reduce their delivery costs (Matkin, 2012). This paper explores some ways of integrating existing MOOCs into post-secondary curricula from an instructional designer’s perspective, and discusses various types of pedagogical support that an institute needs to provide for its programs and faculty to benefit from this educational innovation. History of MOOC In 2008, George Siemens and Stephen Downes offered a course to 25 regular students at University of Manitoba and other 2300 online learners who took the course for free. Three years later, Thrun, a professor at Stanford University attracted over 160,000 online enrollees in his Artificial Intelligence course. Thrun then left his university in 2012 to launch Udacity, a learning organization to pursue his MOOC dream. The year of 2012 was called “the year of MOOC” by the New York Times. It witnessed the rises of several major MOOC providers: Udacity, Coursera, edX. Behind them are some elite universities such as Harvard, Stanford and MIT. Entering 2013, more universities, organizations, and individual have joined the MOOC trend. The major providers started seeking a fee-based pathway to traditional credentials for MOOCs. The interest in MOOC is peaking and the development is believed to be “at the intersection of Wall Street and Silicon Valley” (Caulfield, 2012). Watters had a good summary of the development of MOOC in her blog: http://hackeducation.com/2012/12/03/top-ed-tech-trends-of-2012-moocs/. The rises of major MOOC providers in the United States blur the memory of early exploration in Canada. The MOOC offered by Siemens and Downes in 2008 had significant differences in design from those that made headlines in 2012. Downes called his course “cMOOC”, distinguishing it from “xMOOCs” offered by Udacity, Coursera, edX and others. cMOOCs are built upon the philosophy of Connectivism and follow the practices of open learning and online network that connect people across a common topic or field of discourse. Content in cMOOCs “serves merely as a catalyst, a mechanism for getting our projects, discussions and interactions off the ground. It may be useful to some people, but it isn’t the end product, and goodness knows we don’t want people memorizing it” (Downes, 2011). In a word, a cMOOC is a start point for further exploration. xMOOCs, on the other end, look more like a regular post-secondary course with emphasis on their content (usually are lecture videos and multiple choice tests). They rely primarily on “information transmission, computer-marked assignment and peer assessment” (Bates, 2012, Roscorla, 2012). Issues of MOOC Given the development of MOOC is still at its early stage, many educators have expressed their concerns about the quality of MOOCs, especially that of xMOOCs. Some concerns are summarized here: Some educators have critiqued the design of xMOOCs. Bates (2012) points out that most xMOOCs are built upon an old concept of pedagogy, Behaviorism. Their design supports information transmission rather than higher order thinking. Armstrong (2102) reports that the Coursera courses he observed were basically typical college lecture, chunked into 15-minute segments, and the creators seemed to have no working knowledge of educational research. Daniel (2012) concerns that those elite universities whose strength is research may not be good at online teaching. Bates (2012) challenges one of the Coursera founders about her statement that computers personalize learning in xMOOCs. To him, computers may provide alternative learning paths through material and automated feedback; it is the “online intervention and presence in the form of discussion, encouragement, and an understanding of an individual student’s needs” that give students a sense of being treated as an individual. However, such strategies are largely missed in xMOOCs. Cheating and plagiarism in MOOCs is a threat to quality. In a Coursera MOOC, alleged incidences of plagiarism were so rife that the professor pleaded with the students to stop plagiarizing (Gibbs, 2012a; Young, 2012). edX has partnered with Pearson’s testing centers to offer proctored exams to boost the credibility of student achievement (Kolowich, 2012). The current completion rate of xMOOC is 10% or less (Daniel, 2012). The completion rate has been seen as one of the key criteria for quality assurance. Though it could mean something differently in MOOCs (Balch, 2013), the low completion rate associated with MOOCs remains a quality concern for some educators (Watters, 2012). Lane and Kinser (2012) worry that the MOOC format - delivering the same course to a massive number of students across the world could lead to the McDonaldization of higher education that diminishes “both the diversification of the higher education sector and the advancement of globally engaged students and institutions” (2012). Integrating MOOCs into Curricula The design and development of a course follows the principle of alignment. In a well-designed course, three major curriculum components - learning outcomes, learning activities and assessments should align with one another and reinforce one another (A learning activity includes content materials and instructions that help students achieve certain learning outcomes or objectives.). Here, the author uses the principle of alignment as a framework to describe some ways of integrating existing MOOCs in post-secondary curricula. Using MOOC components as learning objects. An instructor has a regular course to teach, though it could be delivered fully online, in a hybrid or a face-to-face format. Usually, the course has a set of predetermined learning outcomes and an assessment plan. When developing learning activities, the instructor may find that some components in a MOOC such as video clips or quizzes are relevant and helpful, and want to refer students to those pieces. The instructor does not want to use a MOOC to replace his or her own design. MOOC components are imported to the course as learning objects and they could come from more than one MOOC. The imported objects could be a complete learning activity (e.g. trying the quizzes) or simply learning contents used in the activities developed by the instructor (e.g. watching the recorded lectures in MOOCs and then participating in a group discussion with guided questions created by the instructor). When MOOC components are used as learning objects, the major learning outcomes of the course may have few overlaps with those of the MOOCs. In this situation, the relevancy of MOOCs to the curriculum is low, and the level of integrating MOOCs into the curriculum is low. Flipping classroom with MOOCs. The flipped classroom model is an instructional strategy that uses technologies to leverage learning in a face-to-face classroom. In a flipped classroom, the typical lecture and homework elements are reversed. Students watch short video lectures at home and spend time interacting with their instructor and peers in classroom to address misconceptions or solve real life problems. If a course shares some of its learning outcomes with a MOOC, the instructor may benefit from such open resources. Instead of developing his or her own content materials, the instructor can simply refer students to the relevant MOOC content for their study at home and focus more on developing learning activities and authentic assessment to engage students in active learning and higher-order thinking in classroom. Usually, the structured content in those xMOOCs tends to be easy to use in a flipped classroom. Again, the content may come from more than one MOOC. In an experiment at Vanderbilt University, Dr. Fisher flipped his classroom using a MOOC. The first ten weeks of the course overlapped with an existing MOOC and the final four weeks was a project, an assessment he designed (Bruff, 2013). San Jose State University has tested this idea in one of their electrical engineering course. The students watched edX lectures at their own time and own pace, and worked in a group of three to solve problems in classroom. The instructor constantly monitored the group performance and interacted with each student. The preliminary research results of this pilot have found performance improvement - the average score of the midterm were higher than usual and coincided with that of MIT students. Students were satisfied with their learning experiences (http://www.sjsu.edu/at/atn/webcasting/events/presscon-101812/index.html). Developing challenge courses for MOOCs. When a MOOC share its learning outcomes with a traditional course, theoretically, the two courses are equivalent. An institute could replace the traditional one with the MOOC to reduce the delivery cost. However, quality issues, such as the lack of personalized learning (Bates, 2012) and potential cheating and plagiarism (Wukman, 2012), set up barriers for credit transfer from MOOCs. Not all post-secondary institutes are ready or willing to accept MOOC credits. In this case, the institutes could develop a challenge course that mainly contains assessments for the MOOC equivalent. Students are required to take the in-house assessments if they want to claim credits for their completion of MOOC. The additional layer of assessment could be authentic in nature to address the quality issues of some MOOCs. A few tutorials or lab sessions may be added to the challenge course to provide personalized feedback and hand-on experience to those who take the MOOC equivalent. Transferring credits from MOOCs. In the history of open education, the effort to offer free no-credit courses has failed (Daniel, 2012). Major MOOC providers are planning to associate credits with MOOCs. This is part of their business model and monetization strategy (Daniel, 2012; Matkin 2012). Both Coursera and Udacity offer “secure assessment” to make their certificates more credible. If MOOCs fit in the curriculum of a post-secondary program, credit transfer is possible. The American Council on Education (ACE) has evaluated and recommended college credit for five Coursera courses. Students can earn ACE credits for taking those courses if they pass an online proctored credit exam at the end (http://blog.coursera.org/post/42486198362/five-courses-receive-college-credit-recommendations ). Supported by the government, in January 2013, San Jose State University and Udacity launched a pilot program to award credits to three of intro-level Udacity courses at a cost one-tenth tuition of their regular classes. In these special versions of MOOCs, enrollment is limited to 100 students per course and “the faculty members will carry the sole authority and responsibility for assessing student learning” (http://blogs.sjsu.edu/today/2013/sjsu-and-udacity-partnership/). Providing learner services to MOOC participants. So far, the author has explored the ways to integrate MOOCs into post-secondary curricula. Post-secondary institutions could benefit from MOOCs by establishing MOOC learning centres, even if no MOOCs fit in their curricula. A MOOC can have local and global learning communities. On the Meetup website (www.meetup.com, retrieved on April 14, 2013), Coursera has more than 2500 meet-ups around the world in which the learners share ideas and form study groups. With access to libraries, labs, meeting rooms and experts, post-secondary institutes are ideal organizers of local learning communities for MOOC participants. Other learner services could include hosting proctored exams, providing tutoring services, or organizing conferences and job fairs related to existing MOOCs. Similar operating model has been successfully supporting distance learners across the word for years. Other than pursuing academic credits, many think MOOCs provide great lifelong learning opportunities and ways to update their knowledge and skills. The need for local learning communities will increase as more and more people participate in MOOCs. MOOC learner services Learning outcomes Learning activities (Content) Assessment Relevancy of MOOC to postsecondary curriculum MOOC as Open Resource Flipped Classroom with MOOC Challenge course for MOOC Credit transfer from MOOC Defined by MOOC Defined by instructor/ few overlaps with MOOCs’ Defined by instructor/ overlaps with MOOCs’ at various levels Defined by instructor/ overlaps with MOOCs’ Defined by instructor/ overlaps with MOOCs’ Organizing learning communities and hosting proctored exams, etc. Designed by instructor/ using MOOC components in some learning activities In classroom activities designed by instructor/ studying MOOC at home Using MOOC activities/ adding a few tutorials or lab session Using MOOC activities Using proctored exams in MOOC Designed by instructor Mainly designed by instructor Mainly designed by instructor (additional layer of assessment) Using proctored exams in MOOC Low Pedagogical Support To benefit from existing MOOC, the post-secondary institutes need to provide a variety of support in terms of curriculum development, instructional design, and faculty development, to their programs and faculty members. Outcome-based or competency-based curriculum. In the four out of five ways of using MOOC resources discussed in this paper, the institutes or faculty members have control over their curricula. The extent to which a MOOC is integrated in a curriculum depends on how the MOOC fits in or is relevant to the curriculum. This suggests the importance of a well-defined outcome-based or competency-based curriculum at both program and course level, and a well-categorized MOOC inventory. With these references at hand, it is feasible to find spots in the curriculum where existing MOOCs can be plugged in. If the institutes build their curricular to address both global and local issues and job markets, they will be able to leverage the development of MOOC more effectively and reduce the risk of the McDonaldization of education. High Active learning and authentic assessment. MOOCs are free. Integrating MOOCs or MOOC components in regular post-secondary courses means that instructors could have more time in designing and development active learning activities and authentic assessments. When students learning in distance at their own pace and own time, effective learning communities is key to student success (Mak, 2012; Morley, 2013). However, both instructors and learners seem to need support for communicating online in MOOCs (Gibbs, 2012a, 2012b). Online course development is a team work and experience has shown that an individual faculty is unlikely to produce courses of quality (Bates & Sangra, 2011). Instructors may need extra instructional design support when they flip a classroom, create a challenge course for an existing MOOC, or deliver a MOOC. Instructors as facilitators. In Dr. Fisher’s flipped classroom at Vanderbilt University, students noticed their instructor’s role in the course was different - he was more of a facilitator than lecturer (Bruff, 2013). This is normal in a constructivist or connectivist course. Being a facilitator means the authority in a class shifts from the instructor to students who start having more control over their learning process. Not all faculty members and students are used to such changes. Faculty members may need training to perform well in this new role. The author has explored some ways of integrating MOOCs in post-secondary curricula in this paper. Ignoring the development of MOOC is not wise. It is the time to discuss about the strategies that help us leverage the strength of MOOC and overcome its weakness. As Daniel points out, the real revolution brought by MOOC is that “universities with scarcity at the heart of their business models are embracing openness” (2012). References Armstrong, L. (2012). Coursera and MITx: Sustaining or disruptive? Retrieved at http://www.changinghighereducation.com/2012/08/coursera-.html accessed on Apr. 10, 2013. Balch, T. (2013). About MOOC Completion Rates: The Importance of Student Investment. Retrieved at http://augmentedtrader.wordpress.com/2013/01/06/about-mooc-completion-rates-the-importance-of-investment/, on April 10, 2013. Bates, A.W. & Sangra, A. (2011). Managing Technology in Higher Education: Strategies for Transforming Teaching and Learning. Wiley. Bates, T (2012). What’s right and what’s wrong about Coursera-style MOOCs. Retrieved at http://www.tonybates.ca/2012/08/05/whats-right-and-whats-wrong-about-coursera-style-moocs on Apr. 10, 2013 Bruff, D. (2013). Who are our students? Bringing local and global learning communities. Retrieved at http://derekbruff.org/?p=2558, on April 10, 2013. Daniel, J. (2012). Making Sense of MOOCs: Musings in a Maze of Myth, Paradox and Possibility. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, North America, 3, Dec. 2012. Retrieved at http://wwwjime.open.ac.uk/jime/article/view/2012-18 on Apr. 10, 2013. Downs, S. (2011). Connectivism and Connective Knowledge. Retrieved at http://www.downes.ca/files/books/Connective_Knowledge-19May2012.pdf on April 10, 2013. Gibbs, L. (2012a). Yes, Plagiarism: How Sad is That? Retrieved at http://courserafantasy.blogspot.kr/2012/08/yesplagiarism-how-sad-is-that.html on April 10, 2013. Gibbs, L. (2012b). Peer Feedback: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Retrieved at http://courserafantasy.blogspot.ca/2012/08/peer-feedback-good-bad-and-ugly.html on April 10, 2013. Kolowich, S. (2012). MOOCing On Site. Inside Higher Ed September 7. Retrieved at http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/09/07/site-based-testing-deals-strengthen-casegrantingcredit-mooc-students on April 10, 2013. Lane, J. & Kinser, K (2012) MOOC’s and the McDonaldization of Global Higher Education. Retrieved at http://chronicle.com/blogs/worldwise/moocs-mass-education-and-the-mcdonaldization-of-higher-education/30536, on April 10, 2013 Mak, S. (2012). A reflection of MOOCs Part 3 The yin and yang of MOOCs. Rretrieved at http://suifaijohnmak.wordpress.com/2012/12/17/a-reflection-of-moocs-part-3-the-yin-and-yang-of-moocs/ on April 10, 2013. Matkin, G. (2012). Why MOOCs Are Good for Higher Education (And What MOOCs Will Make Your University Do). Retrieved at http://slideshare.net/garymatkin/ncseonline on April 10, 2013. Morley, M. (2013). Massive Open Online Course (MOOC): Personal experience from MOOCs and their Potential for increasing diversity, social inclusion and learner engagement. Retrieved at http://www.slideshare.net/markuos/mooc-lt-conference-2013-15903824 on April 10, 2013. Roscorla, J. (2012). Massively Open Online Courses Are “Here to Stay”. Retrieved at http://www.centerdigitaled.com/policy/MOOCs-Here-to-Stay.html on April 10, 2013. Watters, A. (2012). Massive MOOC Dropouts: Are We Really Okay With That? Retrieved at http://hackeducation.com/2012/07/23/mooc-drop-out/ on April 10, 2013. Wukman, A. (2012). Coursera Battered with Accusations of Plagiarism and High Drop-Out Rates. Online Colleges. Retrieved at http://www.onlinecolleges.net/2012/08/22/coursera-batteredwith-accusations-of-plagiarism-and-highdrop-out-rates/ on April 10, 2013. Young, J. (2012). Dozens of Plagiarism Incidents Are Reported in Coursera's Free Online Courses. Retrieved at http://chronicle.com/article/Dozens-of-Plagiarism-Incidents/133697/ on April 10, 2013.