Scales of Inequality - CHIA

advertisement

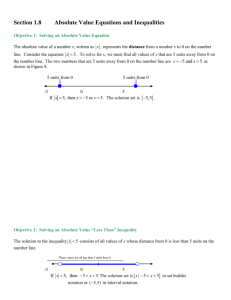

Matt Drwenski University of Pittsburgh March 2015 Scales of Inequality: Strategies for Researching Global Disparities from 1750 to the Present Introduction Sixteen years ago, the novelist William Gibson proclaimed, “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.”1 Over the last few decades, the global distribution of economic resources has remained dramatically skewed but stable. The top quintile of the population controls over 80 percent of the planet’s wealth.2 The top one percent own over 50 percent of global wealth.3 How did humanity build such a polarized world? Recently, several economists, sociologists, and political scientists have begun to address this problem, and have developed a substantial corpus of academic literature describing the available economic data on human inequality.4 Many of these attempts, however, have either failed to leave the Global North, have analyzed the last half century, or have only looked at a single source of data. To answer this question from a world-historical perspective, I must go beyond current measures of inequality taken from the recent, data-rich past and enter into the murkier territory that extends back over the last two centuries and covers the entire globe. This paper employs a comprehensive view of human inequality in order to understand the interplay among differing spatial scales and temporal scopes of interaction. My goal here is to create a new methodological argument for analyzing interpersonal global inequality over the 1 William Gibson, interview by Brooke Gladstone, Talk of the Nation, NPR, November 30, 1999. Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins, “Global Inequality: Beyond the Bottom Billion: A rapid Review of Income Distribution in 141 Countries,” UNICEF Social and Economic Policy Working Paper (UNICER, April 2011), 14; Eric Vanhaute, World History: An Introduction, trans. by Linda Wiex, (New York: Routledge, Kindle Ed., 2013), figure 9.3. 3 Ricardo Fuentes-Nieva and Nicholas Galasso, “Working for the Few: Political capture and economic inequality,” 178 Oxfam Briefing Paper (Oxfam International, January 2014), 2. 4 Jeffrey G. Williamson and Kevin H. O’Rourke, Globalization and History: The Evolution of a Nineteenth-Century Atlantic Economy (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999); Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz and Timothy Patrick Moran, Unveiling Inequality: A World Historical Perspective (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009); Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2014). 2 1 last two hundred and fifty years. In this paper, I lay out a framework for studying world-historical inequality, several strategies for the historical analysis of human inequality, and an outline for an exploratory analysis of inequality. I do this by surveying and critiquing the existing empirical data of a broad range of measurements that pertain to inequality while also laying out a clear typological and methodological approach that can be employed in future historical research. I begin by grappling with how to define inequality among humans and how best to use available quantified data on relational inequality. I then examine the ways in which inequality is measured and described. Next, I attempt to historicize the study of human inequality and review the documented body of historical data. Previous work on inequality—seven large longitudinal databases—is summarized and critiqued. I examine the methodological evolution of historical analysis on economic inequality. I then propose several new strategies to extend of the geographic scope of available historical data to the planetary level. I also suggest ways to refine the granularity of available data to the individual level. Finally, I develop a set of three flexible methodologies that will link data of different categories and from different sources, which will allow for comparisons across time, correlations among different types of data, extrapolations to data-poor localities, and interpolations to create greater detail within localities. Returning finally to the goal of a world estimate of human inequality that will eventually incorporate all forms of available quantifiable inequality, I propose two new studies. The first will summarize human inequality in the last ten years for the entire planet. The second will be long-term research on a single understudy region: the Greater Caribbean. After normalizing the measures in the regionally and temporally selective databases mentioned above, the data can be contextualized alongside new work by historians on non-income inequality (standards of living) at the micro level that is more representative of the planet as a whole.5 I end the paper 5 Robert C. Allen, Tommy Bengtsson, and Martin Dribe, Living Standards in the Past: New Perspectives on WellBeing in Asia and Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005). 2 with a pilot narrative of world-historical inequality that highlights the major trends in the development of inequality at different scales. By viewing inequality at local, regional, and global scales and by combining multiple categories of data, this analysis will enable historians to ask new questions about the interactions among different scales of inequality. The paper presents and explores several lines of inquiry. What definition and understanding of inequality will best serve the investigation of inequality as a world-historical phenomenon? What relationships exist among global and local scales of inequality? How can relatively different types of inequality data, such as wages and height, be correlated and extrapolated to extend the spatial or temporal coverage of the data? How can micro-level historical studies be inserted into national- or macro-level datasets? What broad conclusions can be reached based on the aggregation and harmonization of currently-available historical data on inequality? What further opportunities for archival and methodological improvements exist? Together, these lines of inquiry form the basis for the investigation of world-historical inequality research. Despite the importance of historical patterns of inequality, the mechanisms that drive the changes in social inequality remain a mystery. In order to uncover the mechanisms that create and reproduce inequality at differing scales, I must grapple with five important assumptions. These assumptions arise from the desire to create a global narrative and world-historical conclusions. The assumptions form a framework to investigate inequality and a guide to future analysis of inequality. First, inequality—both today and historically—is only meaningful if studied on a global scale. If my goal is global conclusions, I must employ a global scale of analysis. Prominent world-historical works of the last 40 years have recognized the nature of the globalizing world of the past three centuries and have argued that developments in the political economies of states are affected by and affect regional and global processes. Global 3 processes have an internal structure or, at the very least, have an unevenness to them.6 Second, inequality must be studied in the longue durée. Economists have focused on the immediate past, thus cutting off analysis of long-term historical relationships. Third, the dynamic historical processes that govern inequality can best be analyzed by the historical contextualization of data sources, which will help reveal underlying causal mechanisms. Fourth, only a broad approach to the topic of inequality will be able to connect local distributions of inequality to world-historical conclusions. The share of the world documented through national accounting statistics on wages (from government records on income taxes) and wealth, decreases as one goes backwards in time. Fifth, a comprehensive analysis must also include alternative understandings of inequality that focus on the lived experience of the individual: height, nutrition and caloric estimates, and life expectancy. My goal ultimate goal is to move the study of inequality beyond the limitations of a single statistic, a single region, or a single moment of history. In this work I present an overall framework for the available information on inequality, and then outline strategies of analysis that will elucidate the mechanisms of change in human inequality at different scales. Based on existing data, there are two observable trends throughout the last two centuries in inter-human inequality at the global level. First is the slow rise of inequality from the end of the eighteenth century to the mid-twentieth century among countries and among world regions. The global level of inequality has remained historically high and stable for the last 60 years. Second, a more complex set of trends has played out within localities but, broadly speaking, the regions that exhibit the highest degree of stratification have shifted from a single region, the Caribbean, to Europe and then to developing countries in the twentieth century. I elaborate on the details and complexities of these trends at the end of this paper. As I will argue it is the 6 Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European WorldEconomy in the Sixteenth Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974); Fredrick Cooper, “What Is the Concept of Globalization Good for? An African Historian's Perspective,” African Affairs 100 (2001), 189-213. 4 interconnectivity among local and global scales of inequality that drives change in income disparities. In many ways, inequality eludes a simple definition. Inequality is at once a concept that parallels and crosscuts other categories of difference, such as class, race, ethnicity, and gender. Inequality can cover any relational difference in humans, from exposure to natural or human violence to nutrition to wages. Even though inequality is perhaps an undefinable or unknowable concept, its measurable effects are often clear and quantifiable. In a sense, then, these strategies are most useful for analyzing available and measurable inequality, while still recognizing that this is only a subset of a larger, more nebulous inequality that exists. The real and as yet undecipherable inequality among humans is divided by many more factors than can be measure and, because of this, it will probably be greater than what can be measured. It will be the responsibility of researchers to immerse and contextualize inequality data within the social and cultural dynamics specific to that time and place to recognize and explain in what direction and to what extent the measurements of inequality are insufficient. Observing the quantifiable effects on relational categories and difference among humans is more feasible and useful for historicizing inequality than only pursuing an abstract construction of inequality.7 I can study measured inequality even if I don’t have a satisfactory definition for what actual inequality among humans is. And despite its global scale of analysis, I do not argue for a totalizing understanding of inequality that invalidates work on class, race, gender and their intersections. I am not arguing that all the causes of human difference can be understood through quantification. The various quantifications described in this paper (income, life expectancy, wealth, etc.) do not encompass all of the differences among humans. I focus on measured inequality simply because it is there, it can be quickly analyzed, and the processes that produce it and reproduce it can be historicized to some degree. Other studies that 7 Charles Tilly, Durable Inequality (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 4-11. 5 conceptualize inequality more abstractly or more qualitatively can benefit from the work done here. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, inequality is not inherent among human populations. To be sure, natural variation exists within any group of humans, but historical circumstances have created an unnatural distribution of well-being among and within populations. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, racial differences were commonly used to justify global disparities. More recently—a mere twenty years ago—in a widely discredited study, it was argued that inherent genetic differences in ability and intelligence could explain class stratification at the national level.8 The complete mapping of the human genome and the realization of the similarity of the human species across racial and social boundaries has caused these old arguments to lose credibility. Culture, as a justification of difference, has retained a loyal following. If the justification for global inequality is not based in race, culture, or geography, then it must be based on historical causes, patterns, and cycles. It is my goal to understand, contextualize, and historicize these causal factors through the following definitions, strategies of analysis, and explorations. Defining Inequality: Creating a Typology What types of information and what organizations of this information will be most useful in answering the questions posed in this paper? What definitions will lead to a global estimate of inequality? Inequality is difference. Differences can be discrete or continuous. Discrete differences are often categorical. For example, persons in a population are categorized as peasants, workers, or professionals. This measure shows difference but truncates distribution. It is also unknown whether the difference between peasant and worker is the same as the difference between peasant and professional. A continuous measure of inequality, annual 8 Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994). 6 income or height by person, has potential values of any real number, an infinite set. These data also have an ordered value. Data that are continuous, are easier to enumerate and visualized as distributions. In the gray area between discrete and continuous statistics are ordinal data that have some of the properties of continuous data. For example, if there is information on the average GDP per capita for every country, I can construct distributions and mathematical descriptions for the entire world using these averages. The problem is that the distribution and descriptions produced will not equal a description derived from a survey of the entire world on the individual level. Averages and other measures of centricity inhibit the connection between the local and global that this research has placed as central to understanding inequality. Yet, these ordinal estimates are more abundant in historical datasets. Why are continuous data important to constructing global inequality? First, these data are divisible into new bins or compartments. For example, if you take the income distribution of a country by person or household, the incomes of people or households are divisible into quartiles, quantiles, deciles, and percentiles.9 Continuous data can also be displayed as an unbroken curve. This then allows any individual to be placed in relation to the whole population, even if the population’s boundaries shift, shrink, or expand. Moving up the scale from the individual, localities or nations can then be displayed and analyzed relative to any other scale. Many social scientists, particularly neo-liberals and advocates of modernization theory, stress that inequality should be considered simultaneously as relative and absolute. All types of inequality, however, are fundamentally ways of representing difference, and difference is by definition relative and relational. I reject the idea that a study of inequality should distinguish between two societies based on their absolute well-being. For example, in a hypothetical society with two people, if one person has $1 and another $2, this society should not be treated differently than a society containing one person with $3 and another with $6. While in the 9 Divisions of 4, 5, 10, or 100 parts. 7 second example all parties are better off, any of the people in both examples will recognize that the wealthiest part of society is twice as rich as the poorest part and controls two-thirds of the economy’s resources. Absolutely, the wealthy are only richer by $1 in the first example, as opposed to $3 in the second. Unless I make arbitrary assumptions about what makes a human well-off, absolute difference is not useful for analysis of changes and comparison across time and space. Categorizing Inequality: Earned, Owned, and Lived The available data on economic and social inequality can be divided into three broad categories: earned inequality, owned inequality, and lived inequality. Comparing these categories to create linkages and correlations expands the coverage of continuous data, which is essential to this approach. The strategy here is to divide and conquer. Dividing and categorizing data and then establishing relationships among these categories helps construct a global estimate of inequality by expanding the geographic and global estimations of continuous data. Earned inequality is associated with an abundance of modern statistics. Wages and annual incomes from the national accounting era are available for countries that tax these data. Earned inequality data occur over time, often by year, but they can express a much shorter unit of time, for example: hourly wages. These data are most complete globally for the last thirty years and regionally for North Atlantic countries through the late-nineteenth century. There are also specific localities, cities, or corporations that have available short-term data on earned inequality. Owned inequality is the accumulation of earned wealth and inherited wealth and includes both the financial and physical resources controlled by an individual. Capital, monetary assets, land, and other property are measures of owned inequality. Unlike earned inequality, owned inequality is measured at an instant. In this sense, owned wealth is a snapshot of the 8 results of long-term effects of earned inequality. For this reason, the distribution of owned inequality is often, if not always, more skewed than earned inequality.10 Lived inequality pertains to measures of the lived experiences of an individual. Life expectancy, caloric intake, nutrition, height, and other standards of living come under the umbrella of lived inequality. Like owned inequality, these statistics can be measured at an instant, such as height or life expectancy, or they can be an over-time measure such as yearly calories per capita. Many micro-historical studies are dependent upon accurate understandings of price and cost-of-living data to determine standards of living or average caloric intake.11 Micro-historical studies produce these data, but there are also broad recent surveys of this category at the macro level. Most important to my study, there are historical estimates of lived inequality for areas of the world not covered by the other two categories. The causes and consequences that determine the shape and skew of the distribution of each of these categories of inequality are, of course, interrelated. What are the relationships inherent in the types of inequalities? How does change in one affect change in another? What correlations exist between the three and upon what are these correlations contingent? For example, today in the U.S., the top one percent of income earners receive around 25 percent of the nation's income (earned inequality) but control over 35 percent of its total wealth (owned inequality).12 People in the top percentiles of the distribution of earned inequality generate more surplus wealth each year than those at the bottom, and this is reflected in the above disparity between earned and owned inequality. The three categories of inequality do not cover all potentially measurable—not to mention unmeasurable—forms of inequality. However, they do document areas of action that 10 Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 237-269. Significant work in this area has been achieved by the Global Price and Income History Group: http://gpih.ucdavis.edu/index.html 12 Edward N. Wolff, “Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze,” Working Paper No. 502 (Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, June 2007). Ibid., “Recent Trends in Household Wealth in the United States: Rising Debt and the Middle-Class Squeeze—an Update to 2007,” Working Paper No. 589 (Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, March 2010). 11 9 have historically been used by national policy-makers to correct inequality: redistributive income taxes, estate taxes, public health care, and food assistance programs. Traditionally, economic historians have focused on the first two categories in what is now the Global North and the last category in the Global South. The immediate goal of the methodological strategies presented in this paper is to expand the spatial scope all the categories together through correlation and estimation. In the long run, further empirical research will continue to enhance this approach. What of the other inequalities frequently discussed in current national and international politics? The disparities in levels of education between women and men and among racial or ethnic categories have all been at the forefront of debates in most twenty-first century polities. Inequalities in civil rights often parallel and exacerbate differences in earned, owned, and lived inequalities. I will exclude these inequalities from this methodological argument and cede this ground to the many scholars analyzing these issues with the intention of creating a space within my model for the inclusion of these topics at a later date. This aspect of inequality differs from what I have staked out as my site of analysis in that gender, ethnicity, and race have had less contact with the economic-centric research on inequality. Figure 1. Conceptual Diagram of Inequality The largest circle, “Inequality,” is vast but I identify three overlapping subsets of available and measurable inequality: “Earned,” “Lived,” and “Owned.” From this I seek to draw out estimates at several scales and understand these scales interact with each other and with the system as a whole. Scaling Inequality: Beyond National and Global Estimates Since the rise of national accounting, the nation has been the center for measuring economic activity. It is here, under the bright floodlights of the nation-state, that economic historians have searched for data on inequality. Despite the drawbacks—the changing 10 boundaries and limited historical coverage—of national data, these measures remain the only reasonable way to begin to construct global estimates.13 A consequence of relying on national data is a Eurocentric bias in studying inequality. As one goes back in time, documentation for areas outside Western Europe and North America narrows and then disappears. Scholars who have estimated global levels of inequality for the non-West have relied on guesswork and conclusion-crippling assumptions. For example, data on GDP growth and change in wealth distribution for China, South Asia, Central Asia, Oceania, and Africa have been assumed to be static, or only changing at a fixed rate.14 Researchers derive these measures by projecting backwards from recent statistics or from simple guesswork. One potential work-around is the inclusion of local, micro-economic studies within these global measures. First, I must “account for inequality as a complex set of...interactions that occur simultaneously within and between countries that have unfolded over space and time as a truly world-historical phenomenon.”15 National statistics and local research must be placed in a global framework. When moving from the data-rich twentieth century back towards 1750, national and global estimates may similarly be augmented with more micro-level studies. Recent scholarship has emphasized the interconnectedness of the global economy since at least the late eighteenth century and inequality cannot be an exception to a global-local relationship. Only a few attempts have been made to integrate data from local studies, done in traditionally data-poor spaces, into the broad macro-level estimates of global, historical inequality.16 Micro-level data, from sub-polities, regions, or cities, are also more accurate than estimations and offer a new avenue of connection between scales for analysis. 13 I can imagine a point that micro-level case studies are accumulated to such a degree that older historical estimates are largely abandoned, but that point is very far in the future. 14 Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics, (Paris: OECD, 2001). 15 Korzeniewicz and Moran, Unveiling Inequality, xviii. 16 Branko Milanovic, “A short history of global inequality: The past two centuries,” in Explorations in Economic History 48 (2011): 494–506. 11 The most important distinction when considering scale is that distinguishing within-entity inequality from among-entity inequality. Within-entity inequality treats the individual as the site of the distribution of inequality and bounds the set of the data by a local, national, thematic, or regional border. A survey of annual income by household in the United States yields an example of within-entity inequality. Among-entity inequality is a less desirable but more attainable measure of inequality. For example, an estimate of GDP for countries that compares differences and similarities is a use of among-entity inequality. The Clio Infra project’s work illustrates this point. For example, using their 2000 data on average per capita incomes by country, the Gini coefficient (a measure of inequality detailed in the next section) among all the world’s countries is estimated at 54. If, however, the entire world is treated as a single country (within-entity inequality), then the coefficient is 66.17 A global estimate of among-entity inequality will then differ from within-entity inequality of the globe. The among-entity approach fails to take into account distributions within each country. Traditionally, economists have measured inequality within a single country, and historically studies have often used the aggregation of these measures among countries to assess global inequality. So, these two approaches obscure the relationship between within-entity inequality and among-entity inequality. How then can this argument measure among-entity inequality in a way that is sensitive to changes and continuities within-entities? Since I am interested in how changes at a smaller scale are articulated at the world-historical scale I must find a way around this problem. By setting the scale of analysis as the entire world, I can create a less discrete and more continuous distribution of the global inequality by looking at macro-level inequality as the sum of its micro-level parts. In essence, I must replace traditional among-entity approaches with a within-entity approach at the macro and planetary scale. Among-entity inequality can be treated as within-entity inequality by first replacing discrete or categorical global data with estimates of 17 Joerg Baten, Michail Moatsos, Peter Foldvari, Bas van Leeuwen, and Jan Luiten van Zanden,,“Income inequality since 1820,” in How Was Life?: Global Well-being since 1820, Height and Standards of Living in the Global Past, ed. by J.L. van Zanden et al., (OECD Publishing, 2014), table 11.4, 208. 12 continuous data from the local or national level. The end result will be a planetary within-entity inequality based solely on individual humans aggregated at the global level. Continuous data on inequality, scaled by locality, does exist in two limited cases. First, data on earned inequality are available for the nearly the entire world but only for the past three decades. By looking only at these data, we miss long-term secular or cyclical trends in the structure of global inequality. Second, data for a few North Atlantic countries exist for most of the chosen time period, the present to 1750. A focus on this specific region, however, hides the core-periphery or metropole-colony, relationship on which regional inequality in the North Atlantic depended. The solution to this problem comes from the three categories—earned, owned, and lived—that I established in the previous section. First, I can use the correlations between categories of inequality in times and regions that have data for more than one category. Second, I can use this within-entity data from different categories to create continuous measures of inequality that have the desired global and historical coverage. From these measures, within-entity continuous measures are then summed to create macro-level (regional and global) measures of inequality among entities. Unlike previous among-entity inequality approaches, this new method lacks the drawbacks of comparing categorical estimations by country or region. Essentially, my among-entity inequality has all of the advantages of withinentity measures and allows accurate comparisons among scales. And, as more accurate microlevel data are produced—from new studies on inequality data in a locality—they can easily be incorporated into the global distribution. Measuring Inequality: A Toolkit The Gini index is a useful and simple starting point for measuring the distribution of any type of inequality.18 First, it is a single number between 0, representing perfect equality, and 1, 18 We can also add the Theil coefficient to my single number measures. 13 meaning perfect inequality.19 Second, it is invariable to scale and sample size, but sensitive to any redistribution within the system.20 One calculates a Gini coefficient by finding the difference between the integral of a curve of the cumulative distribution of the data and the area underneath a theoretically cumulative distribution of perfect equality (f(x)=x). It can be applied to any unequal distribution, such as height and calories per day, and not just income. This measure can be used to quickly compare the internal inequality of a city, region, or state with the internal inequality of another entity or with another time. If I calculate a Gini index for the world, then I can easily measure inequality both within entities and among entities. Yet, unless the method from section three for constructing among-entity inequality is used, the Ginis for different scales will not reflect within-entity trends. We can go deeper with a less abstract approach. By emphasizing simple distributions and histograms, quintiles or deciles, I can better observe how smaller scales of inequality fit within larger scales. For example, deciles derived from a local study can be placed within the larger deciles of the global estimate. And, if the data are continuous, as mine will be, I can calculate distributions and cumulative distributions for entities and simply sum these calculations to create macro-level distributions and cumulative distributions.21 This requires the display of the data to be a little more creative, but it also shows idiosyncrasies undetected by an index. More so than with the Gini index, distributions can be compared by their centricity, shape, and skewness mathematically and visually. Historicizing Inequality - What do we know and what can we expect? Before I can launch into my methodological argument for analyzing inequality from the local to global scales, I will pause to quickly examine the available data and what I can reasonable expect to get out of this information. Inequality data exist in three broad types: 19 The Gini can also be expressed on a scale from 0 to 100. Korzeniewicz and Moran, Unveiling Inequality, 120-122. 21 A cumulative distribution of income is known as a Lorenz curve. 20 14 databases compiled by NGOs at the global or regional level, longitudinal secondary datasets constructed by inequality researchers, and micro-level datasets from historical research. By far the largest datasets are those created by non-governmental organizations, such as the World Bank, the Luxembourg Income Study, the UN University WIDER project, and the SocioEconomic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean. These datasets all rely on national government statistics that are then normalized and compiled. Secondary datasets often incorporate the NGO data as a start but supplement these data by combining information from original archival research with the explicit purpose of analyzing the world economy. Table 1. Types of historical inequality datasets. Spatial Coverage Temporal Coverage Type of Data Category of Inequality Granularity Regional/Global NGO Dataset Near complete (almost all parts of the region or globe covered), usually around 80-90% Last fifty years, with better coverage closer to the present. Data are often annual. Countries and occasionally lower-level administrative units within countries Mostly earned inequality (income) with some data on lived inequality Inequality Researcher Dataset A substantial but incomplete global coverage (usually focused on developed countries) Two centuries, one century, or a half century, depending on the study. Data are rarely annual, and often only on specific benchmark years. Country and individual level (usually estimated from larger scale) Income, with usually some consideration of owned inequality (Milanovic and Piketty) or lived inequality (van Zanden et al and Baten) Micro-Historical Dataset A single locality (country, city, neighborhood, subnational unit) From a single year (or month) to several decades Usually at the individual or household level Usually only one measure of inequality but from any of the categories. The final type of datasets, the ones that have so far been used the least in the study of global inequality, are data included in historical studies centered on specific localities. These microlevel data often come from historians interested in topics adjacent to inequality, to which data on wealth, land-ownership, or nutrition are useful supplements to their historical analyses. At present, there are seven large overlapping longitudinal databases, compiled by both NGOs and inequality researchers, that address the topic of world-historical inequality. They are the Maddison Project, the Luxembourg Income Survey (LIS), the Clio Infra project, the World Bank Open Data (WB), the World Top Incomes Database (WTID), the Socio-Economic 15 Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (SEDLAC), and the UNU-WIDER World Income Inequality Database (WIID).22 All seven are briefly summarized in Table 2. First, there several broad commonalities among these databases. Each uses national units as the basis for organizing most of the data. It should be noted that each makes no attempt to account for changing national borders and administrative control. In each database, European states and European settled colonies form the majority of the data with less information from states outside of Europe. This is especially true for data from farther in the past. As I abstractly illustrate in Figure 2, these seven databases are by no means a comprehensive survey of all of humanity for the last two centuries. However, they do illustrate the need for further creation of longitudinal data for countries outside of Europe as well as an opportunity for the inclusion of other sources of historical information. Table 2. Summary of the major inequality datasets. Source What is measured? Spatial Coverage Temporal Coverage Units World Bank Gini Indices, GDP, GNI per capita, Population, Gov’t Salaries Global, but focusing on developed nations 1950-2009 National Units Luxembourg Income Survey Income deciles Europe, US, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand 1960-2011, most countries have 5-10 surveys over the time period National Units Clio-Infra Average Height, Height Gini, Income, Income Gini Global, ~160 countries for the most recent dates, ~40 for the earliest dates 1820, 1850, 1870, 1890, 1910, 1929, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 National Colonial Units 22 The sources for these datasets are as follows: Angus Maddison, Jutta Bolt, and Jan Luiten van Zanden, The Maddison-Project (2013 version), accessed January 10, 2015, http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm; Clio Infra, Clio Infra: Reconstructing Global Inequality, accessed January 20, 2014, https://www.clio-infra.eu/; Janet Gornick, Thierry Kruten , Branko Milanovic, David Leonhardt , and Kevin Quealy, LIS / New York Times Income Distribution Database (2014), accessed January 19, 2015, http://www.lisdatacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/resources-other-nyt.xlsx; The World Bank, World DataBank, accessed January 20, 2015, http://databank.worldbank.org; Facundo Alvaredo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, The World Top Incomes Database, accessed January 15, 2015, http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/; Centro de Estudios Distributivos Laborales y Sociales and The World Bank, SEDLAC - Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean, accessed January 20, 2015, Http://sedlac.econo.unlp.edu.ar/; United Nations University, UNU-WIDER, “World Income Inequality Database (WIID3.0b),” accessed November 5, 2014, http://www.wider.unu.edu/research/WIID30B/en_GB/database/. 16 UNU-WIDER World Income Inequality Database Mean and median income, income Gini, income deciles, income quantiles Global, ~90 countries for the latest dates, ~13 for mid-century 1951-2011 National Units World Top Incomes Database Income and wealth shares for top 10, 5, 1, .5, .1, and .01% of the population, Pareto-Lorenz coefficients Global (European focused, but also including the US, India, Argentina), ~40 countries ~1912 to 2010 National Units The Maddison Project GDP per capita estimates, often calculated through backwards projection Global, ~180 countries Year 1 to 2010 at benchmark dates that increase in frequency as one approaches the present. National Units (including estimates for national units before those national units existed) SEDLAC Income deciles, Gini indices, wages Latin America and the Caribbean, 26 countries Usually ~1980 to 2013 National Units, Metroarea units World-historical inequality research should be in part an attempt to merge these data and estimate inequality distributions for countries that historical studies overlook. From the rough information in the datasets I will reduce the granularity of the information to the individual level and find the accompanying medians, means, variances and standard deviations. One first step will be an estimation of the probability density function of the inequality distribution, using advanced the statistical tools detailed in a later section, for as many countries as possible for the present. Visually, each country will be represented by an elegant and simple curve with the y-axis as inequality and x-axis as the estimated number of people at that level of inequality. Next steps will involve extrapolating the data to cover missing areas and times. Comparisons can quickly be made by merging and stacking these graphs. The global estimate will be a simple summation of these functions. This format will allow for the easier contextualization of local inequality information, as local distributions and even individual and household records can be compared to the national and global distributions. The next section will detail how to arrive at this point and then go further to new studies and broader conclusions about the nature of localto-global inequality and the historical processes underneath these trends. 17 Figure 2. Spatial and temporal coverage of inequality datasets. Approaches to Inequality: The Last Twenty Years Inequality at the global scale has been part of the historical debate since the publication of the works of Adam Smith and Karl Marx. The contemporary approach began with Simon Kuznets’ influential publications in the 1950s.23 Building upon his earlier work on national accounting data, Kuznets’ theories align closely with liberal, Western ideas on modernization, arguing that countries with a high degree of economic stratification represented an intermediate stage caused by their lack of development. Inegalitarian countries would become more equitable as the nation became wealthier overall. Although it provided a convenient justification for high inequality in the Global South, this argument fails to take into account the historical processes that might cause national inequality to be contingent upon the global distribution of resources. 23 Simon Kuznets, “Economic Growth and Income Inequality,” The American Economic Review 45, (1955). 18 In the 1980s and 1990s, Angus Maddison began constructing a bold and pioneering estimate of GDP by country, going back thousands of years. The project’s completion, and continuing revisions and updates, enabled much of the subsequent work on global among-entity inequality.24 His approach generally used modern nations’ GDPs and projected them backwards using a country’s population, estimating the rate of economic growth for each of the periods between several benchmark dates. More recently, two economists of global inequality, François Bourguignon and Christian Morrisson, attempted to create one of the first overviews, using Maddison’s new estimates. These authors also pioneered the use of multiple categories by considering the relationship between life expectancy data and income data.25 Two other studies, published in the decade after Bourguignon and Morrisson’s study, one by Branko Milanovic, an economist at the World Bank, and another by a team of economic historians sponsored by the Center for Global Economic History at Utrecht University have influenced the methodology of this paper by demonstrating how non-income measures, such as height and enumerated occupation tables, can serve as proxies to extrapolate income when adequate data are missing.26 When confronted with two opposing methods for rectifying differing data, such as whether to normalize income by purchasing parity power or exchange-rates, I will follow the example of Timothy Moran and Roberto Korzeniewicz. In these cases, it is better to use both methods for rectifying the data and then examine if and how each method affects the outcome of the analysis.27 Afterwards, I will be able to make an informed choice based on these outcomes. 24 Jutta Bolt and J. L. van Zanden, “The First Update of the Maddison Project; Re-Estimating Growth Before 1820.” Maddison Project Working Paper 4, (The Maddison-Project, 2013), http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddisonproject/home.htm. 25 François Bourguignon and Christian Morrisson, “Inequality among World Citizens: 1820-1992,” The American Economic Review 92 (2002): 727-744. 26 Branko Milanovic, “Global inequality and the global inequality extraction ratio: The story of the last two centuries,” Working paper no. 16535 (MPRA), accessed October 6, 2014,http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/16535/. 27 Korzeniewicz and Moran, Unveiling Inequality, 127-9. 19 In the last ten years, several important studies, including the work of Moran and Korzeniewicz, have been published in what could now be called a growing subfield of historical human inequality. Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty, and numerous other scholars associated with the World Top Incomes project, have demonstrated that a wealth of national sources are available for both income and wealth inequality. The most groundbreaking recent scholarship has come from Dutch researchers.28 As part of the Clio Infra project on global inequality, they have taken the comprehensive, overlapping, and interconnected approach, incorporating economic, political, and social factors. Methodology of Inequality: Creating a Plan of Attack Working with the data Given the current state of the research on global inequality and income distribution, my methodology will need to accomplish three primary tasks. First, it will outline a flexible series of steps for the incorporation of new data from any time, category, or region. Second, localities missing distributions can be estimated using cross-category analogies and extrapolations. Third, this methodological argument will go beyond estimation and quantification of inequality and address more broadly the changes and continuities in global distributions as processes. In doing so, I will attempt to unearth some the underlying historical mechanisms and causal relationships. The following steps formulate the tentative approach for flexibly synthesizing the diverse datasets on inequality with the end goal of creating continuous distributions within entities and among entities. Again, I must include everything from global estimates to micro-level data while remaining statistically rigorous. I start with the benchmark dates created by Maddison’s estimates, which are also used by Bourguignon and Morrisson, Milanovic, and van Zanden et 28 Jan Luiten van Zanden, Joerg Baten, Peter Foldvari, and Bas van Leeuwen, "The Changing Shape of Global Inequality - exploring a new dataset," Working paper no. 1 (Centre for Global Economic History Working Paper Series, 2011), accessed November 10, 2014, http://www.cgeh.nl/working-paper-series. 20 al., 1820, 1850, 1870, 1913, 1929, 1950, 1960, 1980, 1990, and 2002. To these, I will add three new benchmarks—1750, 1780, and 2013—from further extrapolations of Maddison’s data for the first two and a synthesis of the newest data for the latter. Next, I must confront the problem of missing or bad data through historical analogy and extrapolation. For the many nations and regions not covered at these benchmark dates, I will define analogous entities: countries or units that are likely to have similar levels of inequality. Two options exist that can provide analogous entities from which data can be extrapolated. Distributions can be extrapolated forward or backwards in time, or distributions can be extrapolated across space from contemporary entities. For example, Saint-Domingue in 1780 can be estimated by moving backwards in time from nineteenth-century statistics or from more complete data from Jamaica in 1780. This method has been employed before, but most of the connections were made only among countries during the late twentieth century. As a historical analysis, this project will give greater consideration to creating more precise nineteenth- and eighteenth-century data. How will these judgments on which entities are most analogous be made? First, the overall labor regime of the economy will be considered. Was labor primarily free or unfree, and in what proportions? How stratified or mobile was the labor force? Here, the global and historical taxonomy and estimates of labor regimes by the International Institute of Social History will play a key role.29 Second, an entity’s overall orientation and articulation within the world-economy will be assessed. What products are produced here and to what extent is the economy export-oriented? Is the economy part a colonial dependency, a metropole, or neither? From these lines of questioning, future work using my methodologies can generate sets of meso-level historical groupings of entities. This process will begin with places for which I have granular data on inequality. For example, the present-day Northern Atlantic region is formed 29 This on-going work is part of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations: https://collab.iisg.nl/web/labourrelations/results 21 from groupings of English-speaking countries, Scandinavia, Northern Continental Europe, and Southern Continental Europe, each of which have similar within-entity inequality distributions. I could then extrapolate between two countries in Southern Continental Europe. This analysis will bring the above historical reasoning to create overlapping series of changing meso-level scales, which will then be tested for accurate similarities when data are available and used for extrapolation when data are unavailable. My future exploratory analysis will also employ a mostly untried method for enriching the global dataset. As mentioned in section five, there are numerous and varied local studies done by historians. My categories of inequality—owned, lived, and earned—will aid the analysis in an approach similar to the method used in the recent analysis by Bourguignon and Morrisson and Branko Milanovic.30 Instead of just incorporating life expectancy or height data, as these studies did, this project will be able to incorporate a more diverse array of inequality measures. Among the established groupings of meso-level entities are countries with many measures of inequality. For example, Great Britain in 1870 has data on income, rents, land-ownership, and mortality. A distribution for a country that lacks income data in the same meso-level group can be established even if it only has land-ownership data. In a sense, this approach is a more focused version of the previous technique for extrapolation. I can expect more accurate results from this approach, because it is tied closer to real historical data and give it preference over other estimations. This method is especially useful for the earliest part of my temporal scope: as both historical economists and general historians have created useful studies but their findings have yet to be incorporated into the large longitudinal datasets.31 Indeed, historians in general have long been creating data focused on areas considered data-poor. Recently, a spate of historians 30 Milanovic, “Global inequality and the global inequality extraction ratio,” 3. Examples of histories that included details studies of incomes and other distributions of wealth include: T.G. Burnard, “‘Prodigious Riches’: The Wealth of Jamaica before the American Revolution,” Economic History Review 54 (2001): 506-524; Gary B Nash. The Urban Crucible: Social Change, Political Consciousness, and the Origins of the American Revolution, (Cambridge: Harvard U. Press, 1979); Jack P. Greene, Pursuits of Happiness: The Social Development of Early Modern British Colonies and the Formation of American Culture, (The University of North Carolina Press, 1988). 31 22 have published data at the micro level in the pre-industrial and early industrial eras, from height in early nineteenth-century West Africa, wages in eighteenth-century Japan, and productivity in nineteenth-century China.32 These studies combined with continued attempts by historical economists to produce more accurate income distributions for industrialized nations in the longue durée, bode well for this locally-oriented approach. One final and seemingly impossible tool for expanding the data coverage is the so-called bootstrapping technique. Based on an idea similar to Monte Carlo simulations, bootstrapping “uses the observed data to estimate the theoretical and usually unknown distribution from which the data came.”33 By resampling data independently in a way that is representative of the whole one thousand times or more, I can approximate the actual underlying whole that the sample was taken from without resorting to some standard (and possibly inaccurate) assumption, such as the distribution of inequality simply approximates the normal distribution. For much of the data on inequality, from the larger national statistics to local studies, bootstrapping can be employed as a “formal statistical inference using methods that seek to nonparametrically estimate (at least an approximation of) the underlying sampling distribution of inequality measures such as the Gini index.”34 Bootstrapping estimates the unavailable data using the available data. This can be a superior method because, while previous studies have applied normal distributions to a population or retrofitted distributions from more recent studies to older times, bootstrapping need not make any assumptions about the shape of the distribution, hopefully avoiding teleological errors. Less specific data can be bootstrapped into a greater level of granularity, moving distributions closer to my goal of a continuous curve. Bootstrapping can also be used to 32 G. Austin, J. Baten, and B. van Leeuwen, “The Biological Standard of Living in Early Nineteenth-Century West Africa: New Anthropometric Evidence for Northern Ghana and Burkina Faso,” Economic History Review 65 (2012): 1280-1302;. Allen et al., Living Standards in the Past. 33 Philip M. Dixon, Jacob Weiner, Thomas Mitchell-Olds and Robert Woodley, “Bootstrapping the Gini Coefficient of Inequality,” Ecology 68, (1987): 1548-1551. 34 Timothy Patrick Moran, “Statistical Inference for Measures of Inequality with a Cross-National Bootstrap Application,” Social Forces 84, (2006), 1799-1818. 23 produce confidence intervals for Kernel or probability density functions for these non-parametric distributions. Theoretical Innovations My new approach not only needs to be able to add to the scope and scale of the global estimate, but it also needs to enable a researcher to ask and answer new questions on the nature of global inequality. Many social science researchers are primarily interested extracting greater accuracy from the incomplete data on inequality. Of course, I think it is worthwhile, for example, to know whether inequality among humans is converging or diverging in the long run, but the mechanisms and processes of inequality are of an equal importance. Thus, my methodology will need to create room for new theories and develop contributions to the historical nature of global inequality. Here, I seek to expand on the approach of sociologists Roberto Korzeniewicz and Timothy Moran who, in their book Unveiling Inequality, attempt to “move away from technical assessment of current empirical trends” and create “an alternative theoretical understanding of how global inequality has unfolded over time and space.”35 Their study, however, is limited to the last fifty years. While creating better estimates of inequality, I must not lose sight of the goal of creating better theories and historical narratives of inequality to address the interrelation of scales of inequality upon each other. A major theoretical intervention in the study of human inequality is sorely needed. As Barbara Weinstein points out, champions of the traditional macro narratives of Western Civilization already have an explanation for global and regional disparities.36 World-historical inequality should be ready to propose alternatives that highlight the interconnected nature of wealth in industrial and developed economies as dependent upon inequality within and beyond wealthy localities. As a parallel process to the exploratory research to be conducted on world-historical inequality, 35 Korzeniewicz and Moran, Unveiling Inequality, xix. Barbara Weinstein, “History Without a Cause? Grand Narratives, World History, and the Postcolonial Dilemma,” International Review of Social History 50 (2005): 82. 36 24 theory on human inequality must explain the dynamics internal to the global-to-local inequality regime. The distributional shift at local levels must be articulated within the global distribution. Today, the nation-state is one of the most important determining factors in a person’s place in the global distribution. This is to say, location within the world of nations and not location within a single country’s distribution has a greater effect on an individual. For example, knowing whether a person lives in Switzerland or Swaziland predicts that person’s wealth more precisely than knowing whether this person is in the top income bracket in either of those countries. In further studies, I must then think critically on the role of the rise of the nation-state as the gateway of inequality over the past two centuries. The inequality debate needs to be reoriented back towards historical processes—change in trade and labor regimes, the expansion and contraction of empire, economic independence and integration—that I expect are linked to inequality. Of the major studies cited in this paper, only Korzeniewicz and Moran, Williamson and O’Rourke, and Thomas Piketty attempt to incorporate a world-historical mechanism into the narrative. And of these, only Williamson and O’Rourke’s study on the nineteenth-century Atlantic provides an adequate model for discussing historical processes and causal links to inequality. In their study mass migrations and a decrease in the time and cost of shipping caused an economic convergence among the national economies of the North Atlantic.37 The conclusions of future exploratory analysis in historical inequality must include a historical assessment of the mechanisms affecting the interplay between global and local inequality in the long-run. Major historical changes include the end of unfree labor; the mass migrations of the nineteenth-century among Europe; the Americas, Africa, South and East Asia; the world wars (especially their effect outside of the North Atlantic economies); the two waves of imperial conquests and liberation; changes in national tax regimes; post-1950 neo-liberal 37 Williamson and O’Rourke, Globalization and History. The role of the world wars in the rate of capital returns, a major factor for top-level incomes, is well-examined in Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st-century, but the role of these conflicts in the development of inequality outside the industrial world needs further examination. 25 policies; the global population revolution; urbanization; and changes in land-use. Developing this methodology to historicize and approach an explanatory understanding of global inequality over time will be useful to future policy makers as historic processes like climate change have an increasing larger effect on the world economy. Implementation In this final section on my methodology, I return to my key questions. What is the longrun trend in overall global inequality? How do changes in local inequality regimes affect larger scales and vice versa? As I approach implementation of my method, the broad temporal scope and spatial scale of the study will need to be narrowed so that empirical examples can be quickly found and adjustments to my strategies can be made as needed. Two prongs of attack seem like logical choices to achieve this goal. First, only data from around the most recent benchmark (2000-2013) will be considered to create a spatially-comprehensive estimate of global inequality. Even in the data-rich present, I will still need to employ my techniques for creating meso-level groupings, cross-category extrapolations, and data bootstrapping as distributive data is only available for around 90% of the world’s population. Second, I will attempt a temporally-inclusive but spatially-exclusive approach focusing on the Greater Caribbean. This site of analysis will require archive research as well as techniques for the inclusion of this rougher, older data that requires additional massaging before rigorous comparisons can be made. Priorities for Future Work First, an estimate at the planetary level of income inequality (the most document category) is the best place to start for creating conclusions that both test my methodological strategies and show the interplay among scales of analysis. This will also be a model for subsequent work on older benchmark dates. The immediate goal will be the creation of one 26 continuous distribution curve for income. By starting with the average and cut-off decile data from the UNU-WIDER dataset, I can use the bootstrapping technique outlined in the previous section to create a probability density function for the each country and merge these together for a global distribution curve, essentially treating the world as a single entity. World Bank data and the datasets from Clio Infra can be employed to supplement the WIDER data with extrapolations to missing nations. The WTID will also add a finer degree of granularity to the upper tail of this distribution. The end result continuous probability distributions of income for each country and for the world. And unlike other estimates of contemporary global inequality, any individual can be placed within a national, regional, or global scale. The Caribbean as a stand-in for the world will offer historians of human inequality a revealing site of analysis. The Greater Caribbean, defined here as nations that border the Caribbean Sea or the Gulf of Mexico, would be a case study in the interplay among local, regional, and planetary scales of inequality. The greater Caribbean is missing from all of the major studies on inequality and will be the first region examined in my dissertation.38 Though it contains a smaller proportion of human population than other regions, the Caribbean is ideal for this study for a number of reasons. First, the statistical units, both colonial and sovereign states, are remarkably consistent throughout the last two and a half centuries. Caribbean elites of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century also occupied the top level of the global distribution but have since dropped out of the upper echelons. Throughout the examined period, this regional economy was closely linked to economic changes in North America, Europe, Africa, and Asia. Finally, nearly all of the historical processes that have causal links to inequality were articulated in the Caribbean. For example, both the early nineteenth-century and mid-twentieth-century independence movements reshaped the politics of the region. The Caribbean was also the epicenter of the transition from slave labor to free and semi-free labor, 38 In Piketty’s Capital in the 21st-Century, Argentina and Colombia are the only sources for Latin America and the Caribbean. Again, in the The Maddison-Project, Argentina is only source. 27 as well as the rise and fall of plantation agriculture. Millions of Africans, followed by South and East Asians, migrated either permanently or temporarily into Caribbean, and more recently, millions have migrated out of the Greater Caribbean to North America and Europe. Not only is the economic history of the Caribbean a microcosm of the last two centuries of global capitalism, its historical dynamics will help us understand the historical mechanisms that create, sustain, and shift inequality at the regional and global scales. Work done by the Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (SEDLAC) has surveyed income distributions in the region, but only for the last two decades.39 A more in-depth view of the Caribbean will allow historians of inequality to move beyond broad and inaccurate extrapolations. For example, Thomas Piketty uses Argentina’s distribution of wealth as a stand in for most of Latin America.40 When studied over the long-term, the Caribbean can also serve as a test of three of the most important questions that have been studied in detail within the field of global inequality. What is the relationship between peripheral but inegalitarian economies to the rest of the world inequality regime? Thomas Piketty’s generalizations about the nature of economic growth and inequality would appear to hold true for the Caribbean, but without data specifically from these countries it is uncertain whether the Caribbean follows trends first theorized using European sources. Did the migrations among the wealthy North Atlantic economies of the late nineteenth century cause the convergence of wages among these countries? Jeffery Williamson and Kevin O’Rourke’s Globalization and History shows that expanding migrations and faster transportation among the North Atlantic economies are a reason for the convergence of wages among these countries. Without data from other regions—such as the Caribbean—with close economic connections to these industrializing nations, it is difficult to access the broader conclusions for the world inequality or know if factors outside the North Atlantic affected the convergence that created what would 39 40 SEDLAC - Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean. Piketty, Capital in the 21st-Century, 326-328. 28 become the Global North today.41 Roberto Korzeniewicz and Timothy Moran argue that the last fifty years are a period of stagnation in the world as a whole unit, with very few nations moving up or down relative to each other. Are last fifty years of the twentieth-century, a period of stability in the distribution of world as a whole unit, caused by institutions of “selective exclusion” in high-income nations?42 A needed counterpoint to this argument is an examination of the global system during a period of changing distributions of inequality. How do the same state and international institutions function when the economies of the Caribbean are rapidly converging or diverging? This would help illuminate whether the flows of permanent and temporary laborers and international capital in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries do indeed correlate with changes in the global distribution of wealth among countries. This requires the creation of more historical data on inequality. Again, the Caribbean would be an ideal place of to create this data. Together, historical research focused on inequality in the Caribbean over the long-term coupled with global data could answer the big questions about the relationship between different scales of inequality. A Preliminary World-Historical Narrative through Inequality Data Despite all of the work that remains to be done, both in the collection and aggregation of inequality data, the seven longitudinal databases and the several micro-historical studies cited in this paper provide a critical mass of inequality data necessary to sketch a rough historical narrative centered on inequality. This narrative is an example of the conclusions derived from my conceptualizations of inequality and my survey of inequality data. Here, I use Patrick Manning’s example of a global historical narrative through data as a model, albeit with a description more focused on inequality.43 Starting with the world at the end of the eighteenth century and the turn of the nineteenth century, there are some broad similarities in global 41 Williamson and O’Rourke, Globalization and History. Korzeniewicz and Moran, Unveiling Inequality, 76-78. 43 Patrick Manning, Big Data in History, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 20-25. 42 29 inequality. First, average GDP among Europe and its offshoots in the Americas and South Africa are not widely divergent, with the exception of two low-population polities: the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.44 Data on height and caloric intake also show inter-regional similarities between Europe and West Africa, and between Europe and East Asia.45 Thought not covered by the data, several micro-level studies on the Caribbean also exist that argue that this region was the most stratified in the world.46 In the nineteenth century, I begin to see strong global divergence, first in GDP among countries, between Western Europe and Eastern Europe.47 When rough estimates are available for South and East Asia at the beginning of the century (more accurate data exist for the end of the century) the total output of these nations lag significantly behind those of Western Europe and Latin America. For height, nutrition, and general standard of living data, there is broad parity between Asia and Europe until the very end of the nineteenth century.48 The Gini coefficients of income, representing inequality within countries continue to show a remarkable similarity among countries for much of this time period.49 Within-locality data for Africa, the Caribbean, and most of Asia are missing from all these datasets. This nineteenth-century change illustrates the complex relationships among different types of measurable inequality. A growth early in the century in the output of Western Europe leads to a difference in standards of living after a significant time-lag. However, we should be quick to question this as a simple explanation. Changes in the structure of inequality within Asian, African, and Caribbean could contribute to what may amount to a systemic change in the global inequality regime: the emergence of single populous region (Europe) as an outlier in every type of measured inequality. 44 The Maddison Project. Joerg Baten and Matthias Blum,“Human height since 1820,” in How Was Life?: Global Well-being since 1820, Height and Standards of Living in the Global Past, ed. by J.L. van Zanden et al., (OECD Publishing, 2014), 124-128. 46 Burnard, “‘Prodigious riches,’” 506-524. 47 The Maddison Project. 48 Allen et al., Living Standards in the Past. 49 Clio Infra, (Indicators > GDP per Capita and Income Inequality > All countries).. 45 30 Twentieth-century inequality is the story of two large changes. One is the economic shocks of the first half of the century, the World Wars and the global depression, which greatly reduced within-country inequality in Europe, much of the Americas, China, and Japan. To a lesser degree the opposite trend took place in Africa and the rest of Asia. The shock of the World Wars did indeed cause so much destruction that the shares of income and capital of the top percentages decreased all over the globe, most notably in Europe, making the distribution of resources more egalitarian in 1950 within countries than before the depression and war (a few notable exceptions are India and the countries of Southeast Asia).50 Piketty’s analysis of these shocks falls short, while the destruction of capital caused did indeed cause inequality to drop within countries, global inequality among countries increased. The Clio Infra project—using a combination of height data, original research and the UNU-WIDER dataset—calculates world Gini among countries as rising from 49 to 55 over a twenty-year period centered on the Second World War.51 The second trend is a stabilization of inequality among countries (though this obscures the upward movement of many nations) at a historically high level, coupled with the slow but steady increase in inequality within countries.52 Within-country inequality is highest once again in many of the nations of the Caribbean, but this time they are joined by countries from Africa and Latin America.53 Height, nutrition, and other standards of living are distributed more unevenly among countries and world regions at the end of the twentieth century than ever before. In this very brief narrative, different types and scales of inequality continue to react with each other as the global inequality regime changed. Among the world regions, the Caribbean, 50 Joerg Baten, Michail Moatsos, Peter Foldvari, Bas van Leeuwen, and Jan Luiten van Zanden,,“Income inequality since 1820,” in How Was Life?: Global Well-being since 1820, Height and Standards of Living in the Global Past, ed. by J.L. van Zanden et al., (OECD Publishing, 2014), table 11.4, 208; A. B. Atkinson and T. Piketty (eds.), Top Incomes over the Twentieth Century: A Contrast Between Continental European and English-Speaking Countries, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); A. B. Atkinson and T. Piketty (eds.), Top Incomes: A Global Perspective, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). 51 Baten et al.,“Income inequality since 1820,” 208. 52 Korzeniewicz and Moran, Unveiling Inequality, 68-72; Baten et al.,“Income inequality since 1820,” 205-211. 53 UNU-WIDER, “World Income Inequality Database (WIID 3.0b).” 31 Africa, and Southeast Asia all need comprehensive longitudinal estimates of all the major measures of inequality. In the meantime, an incorporation of micro-level data can bridge the gap in missing information and allow for the construction of world-historical narrative that incorporates the local-to-global and global-to-local consequences of historical change. 32