File

advertisement

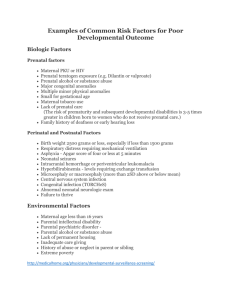

Community Needs Assessment: Low Birth Weight and Infant Mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives in King County, Washington Contemporary Nutrition TR6122-B Final Project March 22, 2013 Melissa Hsu, Laura Prevo, Kali Tupper, & Katherine Ueland i Table of Contents 1 SECTION I: Introduction 2 SECTION II: Cultural Community/Target Population 4 SECTION III: Rationale and Significance 7 SECTION IV: Conclusion 8 SECTION V: References i I. Introduction American Indians and Alaskan Natives (AI/AN) experience large health disparities compared to other races in the United States.1,2 This population also experiences a greater infant mortality rate (IMR) than other races.3 According to the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) between the years of 2000 to 2004, 119 AI/AN fetal deaths occurred out of a total 3,414 in Washington State.4 In King County, WA from 2000 to 2002, AI/ANs had an IMR of 18.8 per 1000 live births, over 4 times that of white rates.5 This rate was alarming, as it was higher than all other periods in the 1990s.5 From 2003 to 2007, the combined IMR was highest in the AI/AN population in King County, at 13.7 per 1000 live births, compared to all other races, including white IMR at 3.4 per 1000 live births, and African American IMR at 8.6 per 1000 live births.5 This is an increased IMR in the AI/AN population, after a decline from 2003 to 2006.5 The current IMR is improved from the 3-year rolling average rates from 2000 to 2004.5 These improvements may reflect decreases in smoking and alcohol consumption, and small increases in early prenatal care (in the first trimester), and decreases in late or no prenatal care.6 For AI/ANs using prenatal care, or utilizing prenatal care before the third trimester, IMRs improved.6 Despite improvements in IMRs and prenatal care access in the Northwest AI/AN population, IMRs were still higher than the Healthy People 2010 objective of ≤ 4.5 per 1000 live births.6 Prenatal care objectives also were not met.6 Very low birth weight (VLBW) and low birth weight (LBW) at birth are associated with the increased IMR for this population.4 Many of these neonatal and perinatal deaths can be avoided with adequate prenatal health care including nutrition counseling.4,7 1 II. Cultural Community/Target Population Target Population The target population of this needs assessment consists of AI/AN females of childbearing age located in King County, WA.3 Childbearing age is defined as the period in a woman's life between puberty and menopause.7 In 2006, a mother’s average age at first birth in Washington state is 25.9 years.8 AI/AN women had the youngest average age of 21.9 years.8 A study by the Centers for Disease Control found there was a strong association between young maternal age and high infant mortality and between young maternal age and a high prevalence of LBW and VLBW.9 In 2010, 7.6% of AI/AN births in the United States were considered to be LBW, while 1.3% were VLBW.10 LBW is defined as less than 1,500 grams (3 lb. 4 oz.), while VLBW is less than 2,500 grams (5 lb. 8 oz).10 According to The Health of King County Report 2006, 7.6% of AI/AN in King County, WA were LBW, while 1.6% of AI/AN were VLBW.11 There are approximately 14,537 AI/AN in King County, WA.12 In 2010, 29% of AI/AN in King County were living below the Federal Poverty Threshold of $22,050 for a family of four.13 A 2006 study by Castor et al. showed that 11.5% of AI/AN living in urban areas are unemployed, compared to the general population at 6.5%.14 In addition, 18.3% of AI/AN in King County do not have a high school degree, while 80.5% do not have a college degree or higher.15 According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 8% of King County residents lack basic literacy skills.16 A literature and health campaign review conducted by the UIHI in 2011 revealed the need to incorporate AI/AN cultural concepts and practices into health programs, for example, the incorporation of oral teachings or learning by observing.3 Emphasizing strength-based concepts such as self-determination and spirituality may improve health programs.3 In a separate needs assessment report, the UIHI surveyed 34 Urban Indian Health Organizations (UIHO) across the United States, including the Seattle Indian Health Board in King County, and found the following: A need for increased pregnancy and infant health services at many sites since 22% to 35% of sites reported lack of or no referral services for maternity case management, childbirth classes, home or public health nurse visits; more than 17% of sites lacked or did not refer patients for prenatal services, newborn screening, or lactation support.17 More specifically, 48% of surveyed sites had shortages of services or providers, and 70% of sites had shortages of funding or resources to provide adequate maternal, infant, and child health services.17 Environmental issues that impact AI/AN LBW and IMRs Although supermarkets are plentiful in King County (207 supermarkets relatively evenly distributed over the 461 square miles in the Urban Growth Boundary of King County), access to those supermarkets is dependent on having transportation to get to the supermarket and sufficient resources to purchase the food.18 The high rate of poverty among AI/ANs in King County (29%) coupled with frequent lack of transportation, limits their access to healthy food. 17 2 Hsu, Prevo, Tupper, Ueland Lenora Starr, nutrition assistant at the Auburn Public health WIC Clinic and member of the Warm Springs Tribe, confirms that for AI/ANs “transportation is another issue that is a barrier to persons accessing foods” (written communication, February 6, 2013). A 2012 study by Jiao et al. estimated access to supermarkets in Seattle-King County for five low-income groups.18 For groups similar to AI/ANs, with 20% or more below the poverty level and 30% or more with no car, the nearest supermarket was greater than a 10 minute walk for 55% of the group.18 For that same group, 97% were greater than a 10 minute walk to a lowcost supermarket.18 Clearly, access to transportation makes a substantial difference as only 1% of that same group was greater than a 10 minute drive to a low-cost supermarket.18 Overall, the violent crime rate in King County is lower than the national average, with 349 violent crimes per 100,000 people compared to the national average of 429 violent crimes per 100,000 people.19,20 However, a recent qualitative study with AI/AN parents, including discussions with mothers in Seattle, further identified sub-themes of drug, alcohol and tobacco use as well as violence against mothers in the Urban AI/AN environment that may not be reflected in the county average.21 Barriers to care Conflicts between traditional beliefs and Western medical practices exist, sometimes preventing access to prenatal care.3 The distrust of medical providers, perceived racial prejudices, and prior negative healthcare experiences may also contribute to decreased prenatal healthcare.3 Many urban-living AI/ANs cite cost or the lack of health insurance as the main barrier to health care access, or as the reason for delaying care.1 Other barriers to prenatal and maternal care include time constraints, lack of access to or high cost transportation, distrust of government agencies, and/or lack of child care.3 Approximately 67% of AI/ANs live in urban areas with only 15% reporting Indian Health Services (IHS) coverage, making the need for accessible urban health care services essential.1 Often the lack of resources may be the greatest barrier to care. For example, the lack of prenatal care services due to lack of funding or inadequate services in urban areas.3 Program need and urgency A need exists for a program to address LBW and IMR due to the negative risk factors associated with LBW, VLBW, or extremely low birth weight (ELBW), including increased risk of infant mortality.3,4 Later in life, low birth weight increases the risk of high blood pressure, diabetes, and heart disease.3,7 Many of these health issues are completely preventable with adequate access to health care and prenatal nutrition counseling.3,4 3 III. Rationale and Significance A. Primary causes of LBW and infant mortality Infant mortality rates Since the beginning of the Indian Health Board in 1955, IMRs have declined. 22 Although in a 2006 report, the IMR among AI/AN nationwide was 50% higher than in non-Hispanic whites (8.3 and 5.6 per 1,000 births, respectively).23 Causes of death and risk factors for infant mortality within AI/AN include Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), with AI/AN population having a 115% higher incidence rate than nonHispanic whites (119.4 and 55.6 per 100,000 live births respectively).3 Infections and unintended injuries are also high among AI/ANs compared to other populations.23 Access to Prenatal Care One of the leading causes of LBW and IMR among AI/ANs is lack of access to prenatal care.3,4 Although in recent decades, with the help of the Indian Health Board (IHB) access to prenatal care has increased among AI/ANs but still lags behind other ethnic groups.24 Overall, between 1990 and 1998, there was an increase in the proportion of mothers who were receiving prenatal care within the first trimester, but the rate for AI/ANs still lagged behind. 24 Many AI/ANs have been displaced from their homes and have had to move into cities and urban areas.22 This has resulted in a loss of community and sense of place preventing many women from knowing where to go for assistance when they become pregnant.3 Because of this, many women do not receive prenatal counseling and nutritional services to help assist them through a healthy and successful pregnancy.3 The large-scale relocation from rural reservations to urban areas has resulted in a loss of access to tribal health services and exacerbated health disparities within AI/AN populations.24 One study of the AI/AN population in U.S. metropolitan areas found that 14.4% of urban AI/ANs receive inadequate care during their pregnancy, and 5.7% of births resulted in low birth weight infants.22 In an earlier study comparing risk factors in poor birth outcomes, inadequate access to prenatal care was significantly higher among AI/ANs living in rural areas than in urban areas (18 % and 14% respectively) with whites having the lowest inadequate prenatal care at 7%.25 The health status of urban AI/AN women and infants is of particular importance because, in most cities, these children are not eligible for or do not have access to health services provided directly by the IHS or other urban tribal health programs and are left without care.25 In a study examining disparities in prenatal care, AI/AN’s unadjusted rates of inadequate prenatal care from 1985–1987 was 36.3% and decreased in 1995–1997 to 26.3%.25 Postneonatal death results from 1985–1987 were 7.1 per 1000 and in 1995–1997 had decreased to 4.8 per 1000, improving significantly.25 However, when adjusted for confounding factors disparities between AI/ANs and whites in postneonatal death, inadequate prenatal care persisted.25 4 Hsu, Prevo, Tupper, Ueland B. Secondary causes of LBW and infant mortality Marital status and maternal age Other risk factors that result in poor birth outcomes show that AI/ANs are more likely to be unmarried than non-Hispanic whites (59% and 22% respectively).24 AI/ANs were also more likely to be less than 18 years of age compared to non-Hispanic whites (8% and 3% respectively) and living in a non-metropolitan area (71% and 50% respectively).24 Hypertension, diabetes, smoking and alcohol use AI/ANs also have significantly higher levels of hypertension, diabetes, smoking and alcohol use than the other ethnic groups, all of which contribute to LBW and infant mortality.3,24 In a recent study, AI/ANs had a higher incidence of hypertension, diabetes, smoking and alcohol consumption (5.5%, 4.8%, 21% and 3.5% respectively) compared to nonHispanic whites in the same categories (4.5%, 2.6%, 16.4% and 1.2% respectively).24,26 Socioeconomic Status As a whole, the AI/AN population also faces socioeconomic disparities as evidenced by high rates of unemployment, poverty, and low educational attainment.3,24 Data limitations for AI/AN Despite the widespread recognition of the challenges faced by AI/AN populations, relatively few nationally representative, population-based studies of the health status of AI/AN mothers and infants have been conducted.3 The available data on how risk factors affect low birth weight and infant mortality among the AI/AN population is dated.3 This skews the interpretation of the data as it may not reflect the current status of AI/AN women and infants.3 There is a limited amount of current original research that has investigated LBW and IMR.3 Further investigations are necessary to understand the current state of LBW and IMR. The AI/AN population has become increasingly urbanized during the past several decades and there is relatively little information that specifically describes the perinatal health status of AI/AN women and infants who reside in urban areas.22 Further studies are needed in this area to account for the many AI/ANs who have left the reservations and their communities and integrated into urban living. C. Health care communication campaigns/efforts in the AI/AN community The Coming of the Blessing® In 2008, the AI/AN Women’s Committee of the March of Dimes West Region pilot tested a comprehensive prenatal health education booklet called The Coming of the Blessing®. 27 This booklet incorporated native cultural beliefs and traditions to honor the period of pregnancy and childbearing in these women’s lives.27 The booklet was pilot tested in 14 states. 27 Evaluation of feedback from 181 women in 40 nations from 10 of the 14 participating states 5 revealed an increase in prenatal care utilization from 66% to 76%, a decrease in preterm birth rates from 14.6% to 7%, and 90% of the women reported taking better care of themselves during pregnancy including improving diet/exercise habits, stress reduction, making the decision to breastfeed, and changes in smoking/drug use.27 All of the outcomes of the prenatal health education booklet may improve birth outcomes and decrease the IMR in this population.27 Due to the positive response to the booklet, The Coming of the Blessing® is now available in every state through the March of Dimes Fulfillment Center.27 Prenatal home visits A randomized control trial in 2009 found that prenatal home visits to disadvantaged women significantly lowered the incidence of LBW.28 The study was conducted among pregnant women who lived in New York State communities with high rates of teen pregnancy, LBW babies, infant mortality, Medicaid births, and mothers with late or no prenatal care. 28 Pregnant women were randomized to receive either no home visits or bi-weekly visits lasting at least one hour with a woman of similar cultural background who had received extensive training by Healthy Families America. 28 The group with home visits delivered babies with LBWs at a rate of 5.1% compared to a rate of 9.8% for the control group. 28 Prenatal home visits are one way shown to reduce the risk of LBW babies in disadvantaged populations.28 WIC participation Analysis of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Birth Cohort identified WIC participation as protective against LBW for all ethnic groups, including AI/AN.29 Accounting for multiple variables such as poverty status, health insurance, age of mother, and smoking status the odds ratio of having a low birth weight infant for mothers using WIC in the past 12 months was 0.68 (0.53 - 0.86), showing a protective effect.29 Seattle Indian Health Board For the past 35 years the Seattle Indian Health Board (SIHB), a non-profit organization, has served the needs of AI/ANs in the greater Seattle/King County region of Washington State.30 One of the many services offered at SIHB is maternal and infant health services.30 These services include preconception care, free pregnancy testing, maternity support services, home visits, prenatal meetings/childbirth education sessions, labor and delivery support, well child exams, dental exams for infants and provides an in house Women Infant and Children (WIC) program and nutrition. 30 The WIC program at SIHB is unique in that the office is onsite at SIHB to accommodate women who receive other services at SIHB to have one stop services.30 It is rare for an organization like SIHB to have a WIC office onsite. 30 In a conversation with Heather Graham, Coordinator for WIC program, DTR, and Internationally board certified lactation consultant (personal communication, March 5, 2013) she explained that the WIC program is a great asset to SIHB and the breastfeeding program is very successful and well-funded in the state of Washington. Currently, the case loads at WIC at SHIB are high due to the persistent follow-ups with the patients and also due to their participation in outreach programs. During the conversation in March, Heather also 6 Hsu, Prevo, Tupper, Ueland commented on the weekly prenatal meetings that are held on Thursdays for pregnant women and women who have recently given birth. She explained that each woman and child receives a free lunch and is encouraged through group discussions to share their experiences either with pregnancy or childbirth. A Native American elderly women attends these luncheons, and is a mother who breastfed all of her children. She educates the women on the importance of breastfeeding, by sharing her own success stories. The weekly luncheon provides a space for women to form bonds with each other in their culture and create a community around childrearing. Native Generations Campaign A new program addressing infant mortality in the AI/AN population, including LBW, is the Native Generations campaign recently launched by the UIHI and funded by US Department of Health & Human Services.31 The campaign recently launched a video that shares the stories of young urban AI/AN parent that wish to stay connected to their culture after being displaced from their families.31 The video promotes a nationwide network of UIHI organizations that provide health services and ways to stay connected to their communities.31 The campaign has a website that provides many free resources for expecting parents and caregivers as well as current reports from UIHI on maternal and child health practices for AI/ANs.31 IV. Conclusion The success of past and present health care campaigns and efforts in the nationwide AI/AN community to decrease LBW and IMR reveal the need for similar programs in King County. It is also important to integrate AI/AN cultural practices and concepts, tailor the programs to suit the diversity of the population, develop programs in collaboration with the AI/AN communities, and ensure sufficient resources and access to prenatal care. With adequate awareness, support, resources, and nutritional counseling, LBW and many infant deaths are preventable in this community. 7 V. References 1. Fact sheet: Affordability of health care for urban American Indians and Alaska Natives. Urban Indian Health Institute website. http://www.uihi.org/wpcontent/uploads/ 2012/11/Fact-sheet_ NHIS_Affordability-of-health-care.pdf. November 2012. Accessed February 20, 2013. 2. Jones DS. The persistence of American Indian health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2122-34. 3. Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Looking to the past to improve the future: Designing a campaign to address infant mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Urban Indian Health Institute website. http://www.uihi.org/wpcontent/uploads/2011/07/Healthy-Babies-Lit-Review-Final_JulyRev.pdf. Published January, 2011. Accessed March 14, 2013. 4. Fact sheet: Fetal and infant deaths and perinatal periods of risk among American Indians and Alaska Natives in Washington. Urban Indian Health Institute website. http://www.uihi.org/wpcontent/uploads/2009/04/ppor_fact_sheet_final1.pdf. April 14, 2009. Accessed February 20, 2013. 5. Washington State Department of Health, Center for Health Statistics, Linked Birth-Infant Death Data. Public Health Seattle and King County website. http://www.kingcounty.gov/ healthservices/health/data/chi2009/HealthOutcomesInfantMortality.aspx. Updated December 14, 2011. Accessed March 14, 2013. 6. Gaudino Jr, JA. Progress towards narrowing health disparities: First steps in sorting out infant mortality trend improvements among American Indians and Alaska Natives in the Pacific Northwest, 1984-1997. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:S12-S24. 7. Brown, JE. Nutrition Through The Life Cycle. 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2011. 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Delayed childbearing: More women are having their first child later in life. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db21.htm. Accessed March 8, 2013. 9. Friede A, Baldwin W, Rhodes PH, Buehler JW, Strauss LT, Smith JC, Hogue CJ. Young maternal age and infant mortality: The role of low birth weight. Public Health Rep. 1987;102(2):192–199. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1477817/pdf /pubhealthrep00178-0074.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2013. 10. National Vital Statistics Reports, Births: Final Data for 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_01.pdf#table01. Accessed March 9, 2013. 11. Public Health - Seattle & King County, Health of King County Report, 2006. http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/data/hokc.aspx Accessed March 21, 2013. 12. U.S. Census Bureau, 2007-2011 American Community Survey. http://factfinder2.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/11_5YR/DP05/0500000US53033. Accessed March 6, 2013. 8 Hsu, Prevo, Tupper, Ueland 13. Communities Count, Racial and ethnic group differences in poverty persist in King County. http://www.communitiescount.org/index.php?page=race-ethnicity-3. Accessed March 15, 2013. 14. Castor ML, Smyser MS, Taualii MM, Park AN, Lawson SA, and Forquera RA. A nationwide population-based study identifying health disparities between American Indians/Alaska Natives and the general populations living in select urban counties. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1478-1484. 15. Public Health - Seattle & King County, King County Community Health Indicators. http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/data/chi2009.aspx. Accessed March 15, 2013. 16. National Center for Education Statistics, State and County Estimates of Low Literacy. http://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/estimates/StateEstimates.aspx. Accessed March 15, 2013. 17. Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Urban American Indian/Alaskan Native maternal, infant, and child health capacity needs assessment. http://www.uihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/MCHNA_RoundII_UPDATEDec2009.pdf. Published December, 2009. Accessed March 14, 2013. 18. Jiao J, Moudon AV, Ulmer J, Hurvitz PM, Drewnowski A. How to identify food deserts: Measuring physical and economic access to supermarkets in King County, Washington. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102(10):e32-e39. 19. Crimes and Crime Rates by Type of Offense. United States Census Bureau website. http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/law_enforcement_courts_prisons/crimes_ and_crime_rates.html. Accessed March 20, 2013. 20. King County, Washington State County Criminal Justice Databook: 1995-2011. Washington State Office of Financial Management website. http://www.ofm.wa.gov/localdata/king.asp. Accessed March 20, 2013. 21. Urban Indian Health Institute, Seattle Indian Health Board. Discussion with Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Parents: Keeping Babies Healthy and Safe. Seattle, WA: 2011. 22. Grossman DC, Baldwin L-M, Casey S, Nixon B, Hollow W, and Hart LG. Disparities in Infant Health Among American Indians and Alaska Natives in US Metropolitan Areas. Pediatrics. 2002;109:627–633. 23. Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2006 period linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2010; 58 (17):1-10. 24. Alexander GR, Wingate MS, Boulet S. Pregnancy outcomes of American Indians: Contrasts among regions and with other ethnic groups. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12: S5–S11. 25. Baldwin LM, Grossman DC, Murowchick E, Larson EH, Hollow WB, Sugarman JR, et al. Trends in Perinatal and Infant Health Disparities Between Rural American Indians and Alaska Natives and Rural Whites. Am J PublicHealth. 2009; 99: 638–646. 26. Chamberlain C, Yore D, Li H, Williams E, Oldenburg B, Oats J, et al. Diabetes in pregnancy among indigenous women in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: a method for systematic review of studies with different designs. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2011; 11:1-8. 27. March of Dimes. The coming of a blessing. March of Dimes website. http://www.comingoftheblessing.com/Resources.html. 2012. Accessed March 19, 2013. 9 28. Lee E, Mitchell-Herzfeld SD, Lowenfels AA, Greene R, Dorabawila V, DuMont KA. Reducing Low Birth Weight Through Home Visitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Prev Med. 2009; 36(2): 154-160. 29. Sparks PJ. One Size Does Not Fit All: An Examination of Low Birthweight Disparities Among a Diverse Set of Racial/Ethnic Groups. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:769-779. 30. Seattle Indian Health Board. Clinical Services – Maternal and Infant Health. http://www.sihb.org/maternal_infant_health.html. Accessed March 20, 2013. 31. Native Generations, A division of the Seattle Indian Health Board. http://www.uihi.org/projects/native-generations/. Accessed March 21, 2013. 10