Address to the Graduating Class ofBishmizzine High Schoool

advertisement

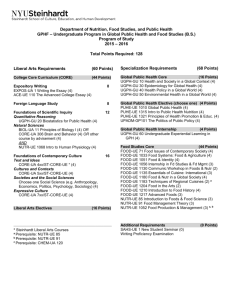

Address to the Graduating Class of Bishmizzine High School Saturday, July 3, 6:00 pm Principal Khaleel, esteemed colleagues, graduating students, families and friends… It is an honor to be invited here today to address Bishmizzine High School’s 2010 graduating class. As you know, many BHS students went on to attend the American University of Beirut before making their mark on the world as scholars, intellectuals and innovators. Some of my friends and colleagues studied at BHS. So I am delighted to have this opportunity to express my respect and appreciation for such an admirable institution and the generations of students who have passed through its halls. When I was asked to give this address, I began thinking about my own graduation and trying to recapture all of the emotions that I felt then. I was proud – and a little relieved – but, above all, I was excited about the future. I did not pause to reflect on the years that I had spent at school – my teachers, my friends, my experiences, both good and bad. But I have done so since then and remember those years as a time when I began to understand who I was, what I wanted, and how I might shape my own life. And I admit it – I was a little overconfident. Things seem pretty clear when you’re seventeen – and maybe when you’re seventy. I don’t know yet. But, in between, life is full of surprises and each of them can teach you something about yourself. Like all of you, I thought very carefully before choosing a university major. It was an important decision – one that would set my course for life, or so I thought. In 1980, I graduated from AUB with a Bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering. Ten years later, I left Columbia University with a PhD in Islamic Studies. You heard correctly: BE in Mechanical Engineering; PhD in Islamic Studies. For the past twenty or more years, I have taught and conducted research on the fields of study – scientific, philosophical, religious – that existed in medieval Arabic and Islamic societies. I also specialize in early modern and modern Islamic thought and movements. So what happened? What inspired this radical change in direction? 1 I liked Engineering. It was interesting and challenging, and studying it seemed like a responsible choice, one that fit my own aspirations and those of my parents and my society. But a few years later, when I was working as an aircraft engineer in the United States, I realized that something was missing from my life. Passion. At this point, your parents may be tempted to cover your ears. Not because they don’t understand what I mean, but because they understand all too well. Their primary concern, as parents, is ensuring that you succeed in life, that you go to university; get a well-paying job; advance in the world; settle down and raise a family; maybe help out younger siblings, if need be. They know the importance of the prestige and financial security that come with a professional degree. They don’t want you to take too many risks. They want you to be safe. They’re your parents, after all. Studies have shown that parents, students, and even fresh university graduates all agree that “professional success” is the main reason to obtain a degree, which is essential when entering the job market.1 After five or ten years, however, university graduates make a startling discovery: they realize that the real value of their education is unrelated to their major. We can speculate that this is because some aspects of a professional education become outdated or irrelevant due to new discoveries and approaches, especially in scientific and technological fields. It merely prepares students to enter the job market, where they receive further training and gain experience. But AUB graduates tell us something else. They report that the liberal education which they received at AUB prepared them to live richer lives, not just professionally, but personally as well. What exactly is liberal education? Professor Nicholas Lemann, a dean and professor at New York’s Columbia University, suggests that it is best defined quite literally, as: [E]ducation that liberates, that frees the mind from the constraints of a particular moment and set of circumstances; that permits one to see possibilities that are not immediately apparent, to understand things in a larger context, to think about situations conceptually and analytically, to draw upon a base of master knowledge when faced with specific situations.2 Debra Humphreys and Abigail Davenport, “What Really Matters in College: How Students View and Value Liberal Education,” Liberal Education (Summer/Fall 2005). Available online at: http://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/le-sufa05/le-sufa05leap.cfm 2 Nicholas Lemann, “Liberal Education and Professionals,” Liberal Education (Spring 2004). Available online at: http://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/le-sp04/le-sp04feature1.cfm 1 2 It is a common misconception that liberal education focuses solely on the disciplines collectively known as the liberal arts – the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. In fact, a liberal education has two essential components. One is proficiency in a major field of study. At AUB, most undergraduates chose to major in one of the professions, for instance, Business, Environmental Health, or Mechanical Engineering. As Professor Lemann points out, studying a profession in a university, rather than a training school or polytechnic, has definite advantages. While technical schools respond to the immediate personnel needs of an industry, professional schools in universities “have goals and ideals and purposes having to do with the history, the techniques, and the social role of their field[s], which rise above the daily demands of work.” He argues that the graduates of such professional schools “have a collective idea of the good in their work” that is larger than their own self-interest or the interests of their employers. It is this “commitment to a broad and not necessarily utilitarian perspective” that makes liberal education and the professions a “good fit.”3 The second main component of liberal education is a thoughtful general education program that exposes all students, no matter what their major, to key areas of the liberal arts. In recent years, AUB has made sweeping changes to its general education requirement. At one time, students took a series of courses in three disciplines: English; Arabic; and the University’s Civilization Sequence Program, which exposed them to original works by influential thinkers. Now the general education requirement is not restricted to the humanities. Students also take courses in the natural and social sciences, as well as quantitative thought, an area that includes Mathematics, Computer Science and Logic. Some departments offer students guidelines to help them to select the courses that best complement their majors. Even then, undergraduates exercise some degree of freedom of choice. At AUB, we are less concerned with the specific content of the courses – with ensuring that students experience a rigidly defined common or core curriculum – than we are with the broader skills and habits that general education instills in students. As Albert Einstein said, a liberal education is not valuable because it acquaints students with facts, but rather because it trains the “mind to think something that cannot be learned from textbooks.”4 Einstein was talking about critical and creative thinking, two skills fostered by liberal education. While we cannot teach students to be innovative – and we certainly can’t make them Einsteins – we can help to ‘free their minds’ early in their undergraduate years, when they 3 4 Ibid. Philipp [sic] Frank, Einstein: His Life and Times (Da Capo Press, 2002), p. 197. 3 take the majority of their general education courses, and then reinforce these new ways of thinking in major courses at the junior and senior levels. AUB also works to encourage other student learning outcomes, which is the name that educators give to these skills and habits. We are in the process of developing special ‘writing-intensive’ courses in all disciplines to train strong and effective communicators. Other forms of literacy are also receiving attention, for instance, quantitative literacy, which I mentioned earlier, and information literacy. Information literacy prepares students to find information, evaluate it for relevance and credibility, and use it, in an ethical manner, to answer specific questions or solve problems. Note my use of the word ‘ethical.’ All of our general education courses have specially designed ethics modules to acquaint students with ethical issues in the relevant field. Unique courses are also being created to increase student engagement with the community and to help develop leadership skills. Many of our majors require students to complete internships or otherwise practice what they learn. It is our hope that, taken together, these skills and habits will make AUB students into community leaders and lifelong learners. I know what you’re thinking. You just want to obtain a degree and find a job – a good one that pays well and provides opportunities for advancement. You think that employers don’t care about learning outcomes. They just want an employee – a good one, who works hard and lives up to their expectations. In fact, they do care. In January 2010, the Association of American Colleges and Universities published the results of a survey of 302 employers operating medium-to-large enterprises in the United States. Company owners and senior executives agreed that universities “can best prepare graduates for long-term career success by helping them develop both a broad range of skills and knowledge and in-depth skills and knowledge in a specific field or major.”5 These employers were asked to rate a list of learning outcomes that reflected the intellectual and practical skills of valued employees. Here are the items on the list. Each one is followed by the percentage of employers who wanted universities to give more emphasis to that particular outcome: “The ability to communicate effectively, orally and in writing (89%). “Critical thinking and analytical reasoning skills (81%). “The ability to analyze and solve complex problems (75%). Association of American Colleges and Universities, “Raising the Bar: Employers’ Views on College Learning in the Wake of the Economic Downturn,” (bold and italic in original). Survey conducted by Hart Research Associates. Available online at: http://www.aacu.org/leap/documents/2009_EmployerSurvey.pdf 5 4 “Teamwork skills and the ability to collaborate with others in diverse group settings (71%). “The ability to innovate and be creative (70%). “The ability to locate, organize and evaluate information from multiple sources (68%). “The ability to work with numbers and understand statistics (63%).” Employers were also asked to rate more learning outcomes in other categories. I won’t read all of them to you, just the two endorsed by three-quarters or more of the surveyed employers: “The ability to apply knowledge and skills to real-world settings through internships or other hands-on experiences (79%). “The ability to connect choices and actions to ethical decisions (75%). I can guess what you’re thinking. These findings reflect the attitudes of American employers, not those in Lebanon or the Middle East. Things are different here. And they always will be. But are American employers really so different? The global climate for business and finance has changed dramatically in the past few years and few economies have escaped unscathed. It’s true that Lebanon has been relatively fortunate. Places like the UAE, however, which is a key employment destination for Lebanese professionals, have experienced serious slumps in economic activity. There is no room for workers who cannot adapt to rapid and sometimes profound change. And the whole point of a liberal education is to prepare students for change and to help them to avoid the dangers of narrow, inflexible specialization by developing transferable skills and habits. In addition to the current economic climate, which will ultimately stabilize – or so we hope – there are other practical and compelling reasons to focus on adaptability and long-term professional goals. Most employees change jobs six to eight times over the course of their careers. Often this involves radical shifts in the kinds of work that they do. Indeed, if the past decade teaches us anything, it is that many of today’s students are preparing for jobs that do not yet exist. You only have to consider the sudden, phenomenal rise of companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter to realize that new technologies are affecting the marketplace as never before. I mentioned earlier that many Lebanese professionals relocate to the Gulf, where they profit from higher salaries, close proximity to their homeland, and the convenience of a shared language. In recent years, GCC states have been 5 working to establish new universities, which are often based on the American model – think of the American University of Sharjah or the American University of Kuwait – as well as ‘education cities,’ which offer degrees from some of the finest institutions in the US. I suspect that the rulers of these states, who recognize the vital importance of education for development, would agree with a proposition put forward by two Harvard University professors in 2003: “All forms of higher education create national benefits, but liberal education creates a particular set of benefits.”6 These range from the economic, due to the relationship between liberal education and innovation, to policy-making and political participation. The two professors further argue that liberal education reduces the brain drain from developing countries because it stimulates the intellectual climate, making it more likely that educated professionals will remain or return to their homelands. Of course, Lebanese are just as likely to be found in Africa, Europe, or North America. This brings me to my final point – globalization. The world is a marvelously interconnected place these days. Geographical borders have become much less meaningful. A multi-national corporation – or even a university – can be based in one state, set up branches in others, and then recruit employees for their expertise, regardless of their nationality. Outsourcing allows firms to hire from a global employment pool. Our two Harvard professors have something to say about this as well. They note the importance of actual and virtual “networks of expertise’ to a healthy global economy, adding: “This kind of thinking and working is a key feature of a good liberal education, which encourages students to make connections across disciplines and draw on others’ ideas, while working together to advance learning and tackle problems.”7 Liberal education builds on the foundation established by excellent schools – like this one, Bishmizzine High School. Those of you graduating today have probably made your plans, at least for the short term, so my message has largely been aimed at next year’s graduating class – and the classes that will follow. But I hope that you, today’s graduates, will give some thought to AUB’s aspirations for you and to how you can realize them for yourselves, even if you won’t be joining us in the fall. The future awaits you! Make the best of it! Congratulations! David E. Bloom and Henry Rosovsky, “Why Developing Countries Should Not Neglect Liberal Education,” Liberal Education (Winter 2003). My italics. Available online at: http://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/lewi03/le-wi03feature2.cfm. 7 Ibid. 6 6