in linguistics may, 2011

advertisement

QUESTION FORMATION IN MERNYANG

ANJORIN OLUWAFISAYO ABIODUN

07/15CB037

A LONG ESSAY SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT

OF LINGUISTICS AND NIGERIAN LANGUAGES,

FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN,

ILORIN, KWARA STATE, NIGERIA

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR

OF ARTS, B.A. (HONS) IN LINGUISTICS

MAY, 2011

1

CERTIFICATION

This long essay has been read and certified as meeting the requirements of the

Department of Linguistics and Nigeria Languages, University of Ilorin, Nigeria.

……………………………………

DR. MRS B.E. AROKOYO

Supervisor

……………………..

Date

……………………………………

PROF ABDUSALAM

Head Of Department

……………………..

Date

……………………………………

EXTERNAL EXAMINER

……………………...

Date

2

DEDICATION

This project work is dedicated to GOD ALMIGHTY, THE CREATOR OF HEAVEN

AND EARTH. My wonderful parents, Ven & Mrs. P.I. Anjorin, May God bless you richly.

To my Late sister, Olubunmi Anjorin, continue to rest in perfect peace.

3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

My profound gratitude goes to Almighty God, my redeemer, my strength, the author and

the finisher of my faith, you are worthy oh Lord!

The effort of my able Supervisor Dr. (Mrs.) Arokoyo is highly appreciated, may God

continue to strengthen you and continually bless the works of your hand. I appreciate all the

lecturers in the department, Prof Abdusalam, Dr Issa Sanusi, Dr Lere Adeyemi, Dr. Oyebola, Mr

S.A Aje, Mr. J.O. Friday Otun, Mr Rafiu,Mr Ogunlola, Mr Atoyebi, Mr Adeosun, Mrs.

Abubakare, Mrs. Hamzat, you have all blessed my life, may the Lord water your barns.

My gratitude goes to my parents Ven & Mrs. P.I. Anjorin for their support spiritually,

financially, morally and in every aspect of life, you are too much, may you live long to reap the

fruits of your labour. And to my siblings, my late sister who passed away at a tender age, I love

you but Christ loves you more. Ayomide, Ayoola, Ayomiposi, I love you all, may the Lord

bless you.

I appreciate, my one and only partner, Don Babatunde Olaoye you are just too much, may

our relationship bring forth good fruits. The Olaoyes, I appreciate you.

I cannot but appreciate St. Paul’s Anglican Church as a whole, may the Lord bless His

church. Ven Komolafe & his family, God bless you. Rev O.B. Babalola & his family, may the

Lord reward you bountifully, God bless your ministry, Bro. Segun Fadele, Joshua Balogun,

Bunmi Balogun you are all too much.

4

Linguist Tunji Salako, Linguist Bose Ajanaku, my friends Ayodele, Omotola, and all my

course mates I appreciate you and will miss you all.

5

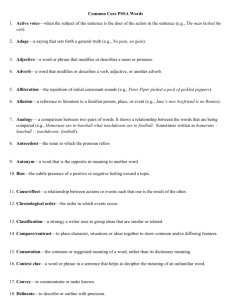

ABBREVIATIONS

Below are the abbreviations of syntactic terms used in this work

AGR

Agreement

C

Complementizer

CP

Complementizer phrase

DET

Determiner

D-S

Deep structure

S-S

Surface structure

I

Inflection

IP

Inflection Phrase

N

Noun

NP

Noun Phrase

Q –m

Question marker

P

pronoun

Spec

Specifier

VP

verb phase

V

Verb

6

And move alpha (which indicates

transformation)

7

TABLE OF CONTENT

CONTENT

PAGE

Title Page………………………………………………………………………………..i

Certification………………………………………………………………………….…ii

Dedication………………………………………………………………………………iii

Acknowledgment……………………………………………………………………….iv -v

List of Symbols and Abbreviations……………………………………………………..vi-vii

Table of Content………………………………………………………………………..viii-xiii

CHAPTER ONE

1.0.

General Background……………………………………………………………………1

1.1.

Historical Background………………………………………………………………….1-3

1.2

Geographical Background of Mernyang People……………….……..………………..3

1.2.1 Socio Cultural profile……………………………………………………………………3

1.2.2

Occupation…………………………………………………………………………..….4

1.2.3 Religion…………………………………………………………………..…………..….4

1.2.4 Festivals…………………………………………………………………..…………..…4

1.2.5 Marriages………………………………………………………………………………..4-5

1.3

Genetic Classification………………………………………………………………….5

8

1.4

Scope and Organization of study……………..…………………………..……….6

1.5

Data Collection……………………………………………………..………………6-7

1.5.1

Data Analysis…………………………..…………………………..…….…………7

1.6

Theoretical Framework..……………….…………………………………………..7-9

1.6.1

X-Bar Theory……………………………………………………………………….10

1.6.2

Projection Principle….……..……………………………………………………....10-12

1.6.3

The Principle of Head Parameter…….……………………………………….……12-15

1.6.4

Theta Theory…………………………………………………………………..........15-16

1.6.5 Case Theory………………………………………………………………………….16-17

CHAPTER TWO

Introduction to Mernyang Phonology and syntax

2.0

Introduction…………………………………………………………………………18

2.1

Basic Phonological Concepts in Mernyang……………………..…………………..18-20

2.11.

Mernyang Consonant & vowel sound system………………….……………………20-21

2.12. Distribution of Mernyang Consonant………………………………………………..21-28

2.13. Distribution of Vowels in Mernyang………………………………………………...28-31

2.2.

The syllabic structures of Mernyang………………………………………….……..31-32

2.3.

Phrase structure Rules in Mernyang………….……………………………………..32-33

9

2.3.1 Noun Phrase…………………………………..…………………………………….33

2.3.2 Verb Phrase……………………………………..………………………………….34-35

2.3.3 Prepositional Phrase…………………………………….…………………………..35

2.3.4 Adjectival Phrase……………………………………………..……………………..36

2.4.

Lexical Categories in Mernyang……………………….……..……………………..37

2.4.1 Noun……………………………………………………….…..……………………37-38

2.4.1 Concrete Noun………………………………………..……………………………..38

2.4.1.2 Abstract Noun…………………………………..……………………………………38

2.4.1.3 Common Noun………………………………..……………………………………..39

2.4.1.4 Collective Noun……………………………..……………………………………….39

2.4.1.5 Countable Noun…………………………..………………………………………….39

2.4.1.6 Uncountable Noun……………………..……………….……………………………39-40

2.4.2. Pronoun………………………………..…..……………..…………………………..41-42

2.4.3 Verb…………………………………..………………….…………………………..42

2.4.3.1 Transitive Verb……………………..………………………………………………..42

2.4.3.2 Intransitive Verb……………………………………………………………………..42-43

10

2.4.4 Adverbs……………………………………………………………………..………..43

2.4.5 Adjectives……………………………………………………………………..……..43

2.4.6 Preposition…………………………………………………………………………...43-44

2.4.7 Interjections………………………………………………………………………….44

2.4.8 Conjunctions…………………………………………………………………………44

2.5

Basic Word order in Mernyang………………………………………………………45-46

2.6

Sentence Types in Mernyang Language……………………………………………..46

2.6.1 Simple Sentence………………………………………………………………………47

2.6.2 Compound Sentence………………………………………………….……………..47-48

2.6.3 Complex Sentence…………………………………………………..………………48

2.7.0 Functional Classification of sentences in Mernyang…………..…………………….48-49

2.7.1 Declarative Sentence……………..………………………………………………….49

2.7.2 Interrogative Sentence…………..……………………………………………………49-50

2.7.3 Imperative Sentence…………………………………………………………...……..50

2.7.4 Exclamatory Sentences………………………………………………………………50

11

CHAPTER THREE

3.0

Question Formation in Mernyang………………………………………………..….51

3.1

Introduction…………………………………………………………………………51

3.2

The WH Question in Mernyang……………………………………………………..51-57

3.3

Yes/No Question in Mernyang…………………………………………………..….58-59

3.4

Echo Question in Mernyang………………………………………………………...60-62

3.5

Alternative Question in Mernyang………………………………………………….62-63

3.6

Tag Question………………………………………………..………………………63-64

3.7

Rhetorical Question………………………………………………………………....64-66

CHAPTER FOUR

4.0

Transformational Processes in Mernyang……………..……………………..………67

4.1

Introduction………………………………………………………………………….67

4.2

Focus Construction……………………………………………………….………….67-70

4.3

Relativization………………………………………………………………………..70-79

4.4

Reflexivization………………………………………………………………………79-83

12

CHAPTER FIVE

5.0

Summary and Conclusion……………………………………………………………84

5.1

Summary…………………………………………………………………………….84

5.2

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..85

5.3

Recommendation……………………………………………………..……………..85- 86

References……………………………………………………………..……………87-89

13

CHAPTER ONE

1.0

GENERAL BACKGROUND

Linguistics over the years has been defined as the scientific study of language.

However, studying language scientifically entails the study of phonetics, phonology,

morphology, syntax and semantics of a language so as to get empirical and sufficient

facts/data, carry them out, experiment and process them, then formalize a rule to form

linguistically significant generalization about such language.

The above mentioned levels of linguistics are referred to as core linguistics by

YULE in that, they as the level at which the structure of any language whatsoever can be

studied, analysed and determined. Hence in this project work, my main objective is to

examine one of the five attested level of language which deals with the arrangement of

words (phrases) to form sentences (i.e. SYNTAX) and my focus will be on question

formation. An aspect which deals with how questions are formed/asked.

This chapter will introduce the historical background of mernyang people, their

socio-cultural profile and the genetic classification of the language. This chapter also

discusses the scope and organization of the study, the theoretical frame work used for our

analysis and the review of the chosen frame work.

1.1

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Oral tradition and history has it that the mernyang people are descendants of

Kofyar people who lived on the hills in Qua’an pan Local government area of plateau

state.

14

Kofyar people are said to have migrated from Dada village in Kano State and the

settlement was founded by Dofyar and nade his sister who were both great hunters.

On the account of their settlement in Kofyar, Dofyar and Nade are said to engage

in hunting expendition when they found themselves on the hills in the northern plateau.

Due to the beauty and attractiveness of the hills, Dofyar and Nade decided not to go back

to Dada (Kano-State) which was their original hometown, but stayed back and made an

abode for themselves on the hills.

After many years, the offsprings of those great hunters grew into a large

community and saw reasons for them to engage in farming to complement their original

and major occupation of hunting. Due to the nature of the hills, some of the people had

to come down from the hills to create a better abode for themselves on the plain surface.

As a result of the height of the hills from the ground, and the hardship

encountered by the people when climbing the hills, some of them decided to stay and

provided shelter for themselves while those that had the going up and down easy decided

to make the top of the hills their permanent abode. Those that decided to stay and live on

the plain surface are today known as THE MERNYANG PEOPLE and the settlement is

named Kwa(or pan) while those on the hills remain as “Kofyar” people. However,

inspite of this, the Kofyar and the Kwa people (Mernyang speakers) still see themselves

as one and they have a mutual relationship.

15

Of many communities and villages in Qua’an Pan Local Government Area of

Plateau State, the Kwa chiefdom i.e. the mernyang speakers remain the major and the

dominant group. They are known and called “the pan chiefdom by their neighboring

villages and towns, and according to the 2005 census, they can boast of 10,000 people

within the community and about 95,000 speakers of the language, they are scattered

around the nooks and crannies of Plateau State.

Educational development, the expansion of settlement and the volume of trade,

agricultural practices and population increase among others have today contributed to

making (Kwa pan) chiefdom enjoy rapid growth and development.

1.2

Geographical Background of Mernyang people

The mernyang speaking people are found in the northern part of Qua’anpan local

government area of plateau state. In the state, they are located as the southern east of the

state

1.2.1 Socio Cultural Profile

The mernyang speaking people have a diverse culture and they distinct from one

another depending on the districts because there are four districts of the mernyang

speaking people. They are: Kwa, which is the mernyang people, Doemak, Dokankasuwa,

Kwang and the Kwalla people.

16

1.2.2 Occupation

As fore mentioned, the main occupation of the mernyang speaking people is

farming. They also engage themselves in trading and hunting and for those close to the

rivers incase of Kwang and Dokan Kasuwa they engage in fishing too.

1.2.3 Religion

Before the coming of the colonial masters, mernyang people were all animist, but

with the coming of Islamic and the Catholic missionaries who settled at Kwa and Kofyar,

some embraced Islam and others Christianity. Today we have Christians and Muslims

and also some of the animist cohibiting together. In regards to Christianity, catholic is the

dominant church because the missionaries that came are from Island and are catholic

missioners.

1.2.4 Festivals

The mernyang speaking people have different festivals depending on the time,

place and district, but there is one general festival been celebrated yearly called Shika’am

where all sons and daughters of mernyang converge to attain and celebrate the festival.

Several talents are displayed to add more beauty and shape to the event. The people also

dance, display magic and the likes. This is done by the youth while elders watch.

1.2.5 Marriages

Marriage in mernyang land differs from district to district, from clan to clan and

religion to religion. In case of Kwa, sometimes a lady is betrothed few days after birth in

which she has to marry the person she is betrothed to or if she refuses she then pay back

what the family of the husband already brought on her behalf even when she was young.

17

Payment of bride price depends on the families and clans.

1.3

GENETIC CLASSIFICATION

AFRO – ASIATIC

Ancient Egyptian

Semitic

chadic

North chadic

West chadic

East chadic

A2

Berber

Cushitic

South chadic

A3 (Angas-Gerka)

1

Cak-fem mushere

Jorlo Kofyar

Bwal Doemak

Goran Jepal

2

Mislup

mwayhand

Kofyar Kwalla

Source adapted from w.w.w ethnologue com/shows= language asp- ?

Code = kwl

18

nyks

MERNYANG

1.4

SCOPE AND ORGANIZATION OF STUDY

This research will focus its attention on question formation. This work aims at

giving a detailed syntactic analysis of the question formation in Mernyang language.

The work attempt to discuss WH question, The Yes or No question, Tag question,

Alternative question, Rhetorical question in mernyang language. This description will

also focus on some of the peculiar features of the language.

This research work consists of five chapters.

Chapter one deals with the

introductory aspect of the work, that is the sociolinguistics profiles of the dialect, its

historical background, socio cultural profile, genetic classification, scope and

organization of the study, theoretic framework. The second chapter centers on the basic

syntactic concept, where we intend to analyze the phrase structure rules as well as the

lexical categories and sentence types based on Government and binding theory.

The third chapter will examine the question formation of mernyang language

while chapter four introduces us to transformational process like focus construction,

reflexivization and relativization. Chapter five summarizes and concludes the work

1.5.

DATA COLLECTION

The method employed for data collection is the bilingual elicitation approach

involving English and mernyang. The data were elicited with the use of the Ibadan four

hundred word list, which consist of basic list of simple words. Apart from the 400 word

19

lists, questions and sentences in English were translated to mernyang by mernyang native

speakers. The data collected were subjected to analysis.

Oral interviews were

questions

conducted in English language and answers to the

were given in Mernyang by my informant. The answers to these questions

were used in the syntactic analysis of mernyang.

Below are the full details of my informant

Name: MICHAEL DAMAN NA’ANKAM

Age:

50 YEARS OLD

My informant is a native speaker of mernyang language. My informant speaks

the following languages; English, Hausa and Mernyang.

1.5.1 Data Analysis

In this research work, the data was collected from my informant both in writing

and recording in an audio cassette then the analysis of the data collected was carried out

using Government and Binding theory of syntax as proposed by Chomsky (1986). This

research work will be limited to the aspect of question formation of Mernyang.

The informants used are fluent in the language, their fluently and competence

formed the basis of choice of them as my informants.

1.6

Theoretical Framework

20

The theoretical framework to be employed in this research work is Government and

Binding Theory (GB). G.B theory is a model of grammar propounded and developed by Noam

Chomsky. This is done with the aim of covering universal Grammar (UG) that is, the system or

principles, conditions and rules that are elements or properties of all human languages. It was

also done as a reaction to transformational Generative grammar to account for all and only the

representations that underline the grammatical sentence in a language.

Government and Binding theory is a modular deductive theory of grammar. Proponents

of G.B. often maintained that there’s no such thing as roles of language but the principles and

parameters whose values can vary from one language to the other do exist with specified units.

Chomsky (1995:15-16) remarks as follows, “The principles and parameter approach held

that language have to rule in anything like familiar sense of transformation and no theoretically

significant grammatical construction, except taxonomic artifacts”.

There are universal

principles and finite array of options as to how such principles apply (parameter) but no language

particular roles.

It is also worthy to note that though Government and Binding theory is a common label

for this model or syntax, it is misleading because it gives undue prominence to the two elements

of government and Binding, whose status was not fundamentally superior to the other subtheories like X-bar, theta, case etc. Hence, the ‘principles and parameters theory’ has come to be

seen as closer to essence.

G.B has two levels of representation related by transformational rule called Move alpha.

Move alpha is stipulated by movement that is the syntactic level is elaborated by the concept of

21

movement (Cook 1988:30) G.B requires two levels of syntactic representation.

The deep

structure (D-structure) which is the level at which we obtain all information on the words and

their combination, it consists of base rules, lexical rules, strict sub categorization, selectional

restrictions, phrase structure rules (Yusuf 19971:68) It is the level at which all the elements in

the sentence are in their original location (cook 1988:30)

We also have the surface structure level (s-structure) which is the level at which some

components in the sentence have been moved. The s-structure is clearly generated from the Dstructure by the application of movement rules. There is a relationship between the deep

structure and the surface structure they are related by movement.

THE SUB-THEORUS OF G.B.

Chomsky postulates a set of interacting sub-theories each of which deals with some

control area of grammatical enquiry. Each of these theories comprises a principle or set of

principles, and each of these may be subject to parametric variation. That is to say, it is assumed

that the grammar of languages vary in only finitely =. Many ways with respect to the domain

covered by a given sub-theory.

All these sub-theories of G.B. theory operates in a modular form, this theory itself is

referred to as a modular deductive theory of grammar. The sub-theory assured are the following:

i.

X-bar theory

ii.

Theta theory

iii.

Case theory

22

iv.

Binding theory

v.

Bounding theory

vi.

Control theory

vii.

Government theory

1.6.1 X-bar Theory

X – Bar syntax replaces large numbers of idiosyncratic rules with general

principles. It captures properties of all phrases and its bases on lexicon. The principle is

that a phrase always contains a head of the same type.

It defines the possible phrase structure configuration of language in general. The

control notion is that each of the major lexical categories (Noun, Verb, Prepositions and

Adjectives) is the head of a structure is dominated by a (phrase, verb, verb phrase, Noun

phrase (NP), preposition: pp and Adjective – AP) it comes after other possible

constituents in the example below.

NP

Spec

N

N1

Det

That

1.6.2

house

Projection Principle

23

Chomsky (1981:29) states that (representation at each syntactic level is projected from

the lexicon) in that they observe the sub categorization properties of lexical items; projection

principles requires lexical properties to be projected to all levels of syntactic representation i.e. a

lexical item projects from its zero bar level to one (single) bar level, which is optional, then to

double bar level. The zero bar level is referred to as the core projection level, the single bar level

is referred to as the intermediate projection level and the double bar level is referred to as the

maximal projection level.

The illustration is shown below:

XII

Maximal projection level

XI

Intermediate projection level

Xo

Core projection level

Horrocks (1987:99) states that X-bar theory tells us that a lexical head (X) and its

complements form a constituent (XI) and that any specifier of this form with a high level of

constituent (XII) Thus:

XII

Spec

XI

XO

Comp

24

The lexical entry projects onto the structure of the sentence, and its influence ceases at

the double bar level. Another feature that makes generalization rule possible in x – bar theory is

the concept of head. The notion of head of a phrase is called the principle of head parameter.

1.6.3 The Principle of Head Parameter

The principle of head parameter specifies the order of elements in a language. The basic

assumption of head parameter is that sentences may be broken into constituent phrase and

structural grouping of words. Stock well (181:70) says that the parametric variation between

language according to whether the position of the head is first or last with respect to its

complement is called head parameter. In other words, all phrases have heads of a related and

possible complement along with some others like its specifiers.

Lamidi (2000:105) says that the head is the keyword in a phrase and the word can be pre

or post modified. In essence, the head of a phrase is very important in x-bar theory and the head

of the phrase to the right or left of the hand is known as head parameter. That is, head first.

X

XO Complement

XI

XO

Comp

Or head last

XI

Complement X

XI

Comp

XO

25

To accommodate specifiers, it requires second level of structure putting the levels of

specifier and complements together, the order of the head and specifier could be set separately

from the order of the head and complement. Thus

XII

spec x

XI

XO comp

Spec

XI

Xo

Comp

All we have been discussing on X-bar (phrase structure) are lexical phrases and the type

of head in lexical phrases is related to word classes. Lexical phrases invariably have heads that

are lexical categories linked to lexical entries.

Another type of phrase is the functional phrase. Functional phrases are the phrase that

are built around functional heads – Functional phrases are the phrases that are built around

functional heads.

Functional phrases invariably have heads that are linked to functional

elements. The functional phrases include inflection phrases (IP).

Cook (1996: 150) says that, inflection phrases are built around functional heads which

may contain lexical materials such as morphological endings but are not required to contain

lexical materials such as morphological endings but are not required to contain lexical materials.

The top levels of the sentence have been unified with the rest of X-bar theory.

26

The maximal

level of a sentence is called inflection phrase (IP) in x-bar theory. IP consists of specifier and II,

II in turn consists of I and a complement thus:

IP

spec

I

I comp

II

IP

II

Spec

I

Comp

Other functional phrases includes complementizer phrase (CP)

CP

spec CI

CI

C

IP

CP

CI

Spec

C

IP

Determinant phrase (DP)

DP

spec

D

DI

D

NP

27

DP

DI

Spec

D

NP

1.6.4 Theta (θ) Theory

Kirsten (1991:493) states that θ theory deals with the functional relationship between a predicate

and its arguments: a predicate is said to assign theta-role to each of its arguments.

It is

concerned with the assignment of what Chomsky calls. ‘Thematic roles’ such as agent, patient

(or theme) beneficiary etc. It is assumed that theta-roles are assigned to the complements of

lexical items as a lexical property. The NP complements (direct object) is assigned to the role of

patient, the PP complement is assigned the role of locative while the subject NP or the sentence

is assigned the agent role.

The main principle of θ theory is the ‘θ-CRITERION’ which requires each thematic role to be

uniquely assigned i.e. each constituent denoting an argument is assigned just one θ role and each

θ role is assigned to just one argument denoting constituent. For example:

Ahmed went to the market by car.

28

IP

II

Spec

NP

I

N1 TNS

(Past)

AGENT NO

VP

AGR

spec

VI

V

NP

PP

N1

PI

NP

PO

NI

Location NO

NO

Ahmed

go

market

by

car

In the illustration above, verb phrase assigns agent role to the subject NP.

Verb assigns patient role to the object of the verb and preposition assigns locative role to its NP

1.6.5 CASE THEORY

Kristen (1991:496) states that ‘case theory regulates the distribution of phonetically

realized NPs by assigning abstract case to them. It deals with the principle of case assignment to

constituents. Chomsky assures that all NPs with lexical contents are assigned (abstract) case.

Case is assigned by a set of case assigners to the governed. Horrocks (1987) says the basic idea

is that case is assigned under government i.e. the choice of case is determined by the governor in

any sentence. For instance, a lexical head X may be said to govern its sisters in X-bar and

certain lexical heads also have the power to case mark certain of their complements. Thus

29

NP subject is assigned normative by INFL; verb assigns accusative case to object of the verb

while preposition assigns oblique case to its object. Let’s use this English sentence as an

example.

Seun bought a land for Biodun

IP

II

Spec

NP

I

NI TN

(past)

NP

AGR

spec

NO

VI

V

VO

PP

NP

PI

Spec

NI

PO

NI

buy

NO

Seun

NP

for

land

NO

Biodun

One of the most important principles of case theory is CASE FILTER, which states that

any s-structure that contains an NP with lexical context but no case is ungrammatical.

30

CHAPTER TWO

Introduction to Mernyang Phonology and Syntax

2

Introduction

This chapter introduces us to the phonological and syntactic concepts of mernyang

language. It focuses on phonological issues like the sound system, syllable structures and

syntactic issues like phrase structure rules, lexical categories, basic word order and

sentence types.

2.1

Basic phonological concepts in mernyang

Mernyang language has thirty-two phonemic consonant sounds and ten vowels. The

description of those sounds is shown below

2.11

/p/:

Voiceless bilabial plosives

/b/:

Voiced bilabial plosive

/m/:

bilabial Nasal

/t/:

Voiceless alveolar stop

/d/:

Voiced alveolar stop

/n/:

Alveolar Nasal

/s/:

Voiceless Alveolar Fricative

/z/:

Voiced alveolar fricative

/L/:

Alveolar lateral

/r/:

Voiced alveolar trill

31

/∫/:

/t∫/:

Voiceless Palato Alveolar Fricative

Voiceless Palato alveolar affricate

/ј/:

Voiced Palatal Approximant

/k/:

Voiceless palatalized velar stop

/g’/:

Voiced palatalized velar stop

/k/:

Voiceless velar stop

/g/:

voiced velar stop

/ŋ/:

velar Nasal

/f’/

Voiceless palatalized labiodental fricative

/d’/:

voiced palatalized alveolar stop

/f/:

voiceless labiodental fricative

/v/:

voiced Labio dental fricative

/Б/:

voiced bilabial implosives

/δ/:

voiced alveolar implosives

/dz/:

voiced palate alveolar affricate

/Y/:

voiced palate alveolar roll

/kw/:

Voiceless labialized velar stop

/gw/:

Voice labialized velat stop

/w/:

Voiced labiovelar Approximant

32

Implosives

Fricatives

Б

j

F

Δ

S

z

F,V

N

L

R

Central

ŋ

Y

back

u:

i

Mid low

e:

Low

u

e

∂

ε

o

ɔ

a

Unrounded

Rounded

33

glottal

?

dz

High

Mid high

Kw

gw

h

J

Front

kg

∫

t∫

Affricate

Nasal

M

Lateral

Trill

Roll

Approximant

Kj gj

Labio

Velar

t,d

Labialized

velar

dj

velar

P,b

Labio

Dental

Bilabial

Stop

Palatalized

velar

voiced velar fricative

Palatal

/ /:

Palato

alveolar

Voiceless glottal fricative

alvelolar

/h/:

Palatilized

Alveolar

Voiceless glottal stop

Palatalized

labio

dental

/?/:

w

The phonemic oral vowel chart of Mernyang

High

ĩ

ũ

Mid high

ê

Midlow

∂

ε

Low

õ

ɔ

ã

The phomemic Nasal vowel chart of mernyang

Distribution of consonant sounds in mernyang

/p/: voiceless bilabial stop

Word initially

[pá]

‘stone’

[pã]

‘ram’

[pà?àt]

‘five’

Word medially

[g∂pãŋ]

‘house’

[kàkàpt∂̃ŋ]

‘bark’

[dàpìt]

‘monkey’

Word finally

[dìp]

‘hair’

[pìέp]

‘beard’

[d∂p]

‘penis’

/b:/

voiced bilabial stop

Word initially

[bàrb]

‘arm’

[biàt]

‘cloth’

[b∂s∂̃ŋ]

‘horse’

Word medially

[m̃bɔ̃m]

‘palm wine’

[jàbà]

‘banana’

[bìubã]

‘rubbish heap’

34

Word finally

[bàrb]

‘arm’

/m:/ Bilabial Nasal

Word initially

[mùɔ̀s]

‘wine’

[mòòr]

‘oil’

[m∂̀̀g∂̀Y]

‘fat’

Word medially

[nàmús]

‘cat’

[n∂̀múàt]

‘toad’

[n∂̀m̀аt]

‘woman’

/t/ voiceless alveolar stop

Word initially

[t ɔ̀ɔ̀ k]

‘neck’

[t ∂m]

‘sheep’

[tàgàm]

‘blood’

Word medially

[k ɔ̀mt∂ǵ]

‘leaf’

[l ∂̀fúk]

‘market’

[àmt∂]

‘thirst’

Word –finally

[fú?út]

‘vomit’

[urεpέt]

‘good’

[miεt]

‘enter’

/d/ voiced alveolar stop

word initially

[d∂p]

‘penis’

[d∂g∂̃l∂ ]

‘room’

[d∂gũŋ]

‘ he goat’

Word – medially

[ndũŋ]

‘that’

[g∂dεt]

‘soon’

[dàd∂̃]

‘bat’

/n/ Alveolar Nasal

35

Word initially

[ndiejεt]

‘smoke’

[niаli]

‘needle’

[n∂̀g∂̀m∂̀m]

‘sea’

Word medially

[g∂̀nɔ̀k]

‘back’

/s/ voiceless Alveolar Fricative

Word initially

[sáY]

‘hand’

[ss∂̀]

‘food’

[súãКωа]

‘maize’

Word medially

[Fu?usbã]

‘sunshine’

[b∂s∂̃ŋ]

‘ horse’

[b∂sĩŋ]

‘house’

Word finally

[àgàs]

‘teeth’

[Lìís]

‘tongue’

[ὲs]

‘bore’

/Z/ voiced alveolar fricative (word initially)

[zὲl]

‘saliva’

[zùgúm]

‘cold’

[zɔgɔp]

‘ pound’

Word medially

[m∂̀z∂̀p]

‘guest’

[dijg∂ɔ∂̃n]

‘urinate’

/L/ alveolar lateral

Word initially

[l ∂gṹ]

‘ dry season’

[lúωà]

‘ meat;

[l̀ὲmú]

‘orange’

Word medially

[dílà̃ŋ]

‘swallow’

[bàldɔ̀gɔ̀l]

‘hard’

[flàk]

‘heart’

Word finally

36

[d∂̀Бdεl]

[dàkаbál]

[lаb∂l]

‘ lizard’

‘crab’

‘ bird’

/r/ voiced alveolar trill

Word medially

[t∫irεp]

‘fish’

[górɔh]

‘kolanut’

[mɔrbã]

‘oil palm’

Word –finally

[jugor]

‘breast’

[nεr]

‘vagina’

[nàr]

‘skin’

/∫/ voiceless palato alveolar-fricative

Word initially

[∫i∫ik]

‘body’

[∫ep]

‘firewood’

[∫аgàl]

‘money’

Word medially

[∫i∫ik]

‘body

[n∂∫аm]

‘ louse’

[nd∂kg∂∫аk] ‘ gather’

/t∫/ voiceless palato alveolar affricate

Word initially

[t∫ig∂n]

‘nail’

[t∫ì]

‘thigh’

[t∫ínì]

‘day’

Word medially

[nt∫ugur]

‘duck’

[nàkùpt∫ís]

‘snail’

/j/ voiced palato approximant

Word initially

[jugur]

‘breast’

[jаbа]

‘banana’

[jil]

‘ground’

Word medially

37

[àjit]

[ndiεjєl]

[g∂̀̀jíl]

‘eye’

‘smoke’

‘earth’

/Kw/ voiceless palatalized velar stop

Word initially

[kjãŋ]

‘hoe’

/gj/ Voiced palatalized velar stop

[gjаrà]

‘hawk’

[gjàiá]

‘dance’

/K/ voiceless velar stop

Word Initially

[kà?àh]

‘head’

[kùm]

‘navel’

[kɔmt∂g]

‘leaf’

Word Medially

[dàkór]

‘tortoise’

[dàkábál]

‘crab’

[nàkùpt∫ìs]

‘snail’

Word Finally

[Ilàk]

‘heart’

[g∂ɔK]

‘back’

[kwаk]

‘leg’

/g/ Voiced Velar Stop

Word Initially

[g∂n]

‘chin’

[gɔ̃ŋ]

‘nose’

[g∂̃nɔk]

‘back’

Word Medially

[tаgаm]

‘blood’

[kugor]

‘Charcoal’

[jаkg∂s∂]

‘men’

Word Finally

[kɔmt∂ g]

‘leaf’

[Бùgàt∂g]

‘tie rope’

/ŋ/ Velar Nasal

38

Word Initially

[ŋkià]

‘vulture’

Word Medially

[bàŋ∂wus]

‘hot’

[nãŋpєh]

‘greet’

[jɔ̃ŋpєh]

‘call’

Word Finally

[gɔ̃ŋ]

‘nose’

[mɔYБã ŋ]

‘oil palm’

[gãŋ]

‘mat’

/FJ/ voiceless palatalized labiodental fricative

Word Initially

[fju]

‘cotton’

/dj/ voiced palatalized alveolar stop

Word Initially

[djip]

‘feather’

j

[d id∂Y]

‘remember’

Word Medially

[ndjik]

‘build’

[peidje]

‘dawn’

/f/ voiceless labio dental fricative

Word Initially

[fù?uh]

‘mouth’

[flàk]

’heart’

[f∂l∂m]

‘knee’

Word medially

[g∂for]

‘town’

[l∂fù]

‘word’

[ùf∂]

‘new’

/V/ voiced labiodental fricative

Word Initially

[vúgúm]

‘hat’

[v∂l]

‘two’

[vãŋ]

‘wash’

Word Medially

39

[pɔgɔu∂l]

‘seven’

/Б/ voiceless bilabial implosives

[Б∂t]

‘belly’

[Б∂lãŋ]

‘work’

[Ба?ãŋ]

‘red’

Word Medially

[d∂g∂̃át]

‘stomach’

[d∂bel]

‘lizard’

/δ/ voiced alveolar implosive

Word Initially

[δɔ̃ŋ]

‘well’/dz/ voiced palato alveolar affricate

[dzàgám]

‘jaw’

[dzέm]

‘matchet’

[dzέp]

‘children’

/Y/ voiced palato alveolar roll

Word initially

[w∂Y∂ʹ ]

‘arrive’

Word Finally

[wаY]

‘road’

[mаY]

‘farm’

[pɔgɔfаY]

‘nine’

/Kw/ voiceless labialized velar stop

Word Initially

[KwаK]

‘leg’

[Kwаkаptõŋ] ‘bark’

Word Initially

[Wukwа? аt] ‘hunter’

[suãkwа]

‘maize’

/gw/ voiced labialized velar stop

Word Initially

[gwui]

‘donkey’

/w/ voiced labiovelar Approximant

Word Initially

40

[wààk]

[wũŋ]

[wus]

‘seed’

‘grass’

‘fire’

Word Initially

[luà? àwàŋ] ‘animal’

[swύm]

‘name’

[bãg∂wus]

‘hot’

/?/ voiceless glottal stop

Word Medially

[pа? аt]

‘five’

[kа?аh]

‘head’

[li?it]

‘elephant’

/h/ voiceless glottal fricative

Word medially

{kahtεp}

‘plant’

Word finally

{ka?ah}

‘head’

{fù?uh}

‘mouth’

{Yógòh}

‘cassava

2.1.3 Distribution of vowels in mernyang

/i//:

high front unrounded vowel

Word medially

[∫ìŋ]

‘motar’

{kæmbì}

‘basket’

{niah}

‘needle’

Word finally

[t∫ì]

‘thigh’

{niali}

‘needle’

[t∫ím]

‘day’

/e/:

Front mid high unrounded vowel

Word midially

[fiew]

‘spin’

[ndemándé] ‘surpass’

[peid’e]

‘dawn’

41

Word finally

[ndèmáńdè] ‘surpass’

[pe;d’e]

‘dawn’

/e:/: front mid high unrounded vowel

Word medially

[pe:d`e]

‘dawn’

/ε/: front low unrounded vowel

Word initially

[ὲs]

‘bone’

[ὲs]

‘feaces’

Word medially

[nεr]

‘vagina’

[t∫εt]

‘cooking’

[dzέm]

‘matchet’

Word Finally

[síε]

‘learn’

[àgàspε]

‘abase’

/∂/: central mid low vowel

Word initially

[∂k]

‘goat’

Word medially

[d∂ba]

‘tobbacco’

[g`∂nɔk]

‘back’

[iahk∂n∂]

‘say’

Word finally

[wupinl∂]

‘husband’

[pem∂]

‘six’

[wàY∂]

‘arrive’

/u:/ : back high rounded vowel

Word medially

[fu:sbã]

‘sunshine’

[fu:s]

‘sun’

/u/ : back mid-high rounded vowel

42

[ùfó]

‘new’

Word medially

[fu?uh]

‘mouth’

[jugur]

‘breast’

[kúm]

‘navel’

Word finally

[lέmú]

‘orange’

[lì?ú]

‘snow’

[lau]

‘bag’

[o] back mid low rounded vowel

Word medially

[lógòh]

‘cassava’

[goóɔh]

‘kolanut’

[dàgó]

‘man’

Word finally

[mũgò]

‘person’

[ũfo]

‘new’

/ɔ/: back low rounded vowel

Word initially

[ɔrũŋ]

‘dust’

Word medially

[kɔʹ m]

‘ear’

[g`∂n`ɔnk]

‘back’

[ńbɔm]

‘palm wine’

/a/ : back low unrounded vowel

[ajit]

‘eye’

[àgàs]

‘teeth’

[àm]

‘water’

Word medially

[jàp]

‘divide’

[lat]

‘finish’

[nàr]

‘skin’

Word finally

43

‘child’

‘father’

‘son’

[làlà]

[ńda]

[là]

2.2

The syllabic structure of mernyang

Ladefoged (1976:26) defines a syllable in terms of the inherent sonority of each sound.

The sonority of a sound is relative to that of other sounds with the same length, stress and pitch.

A syllable has been defined as a peak of prominence which is usually associated with the

occurrence of one vowel or syllabic consonant (Hyman 1975:189). A close syllable ends with a

consonant, while an open syllable ends with a vowel.

Mernyang language exhibits open and close syllable structures. The syllable structures in

mernyang are described as CV, VC, CVC, CVCV, CVCVC, VCVC, CVCVCVC. Syllables

examples of words in the language with their syllables structures are given below:

2.2.1 Mono-Syllabic Structures

These are words that have a single syllable. Examples include:

[t∫ã]

‘hoe’

[tєp] ‘tear’

[nàs] ‘beat’ [person]

[wút] ‘untie’

Di syllabic

These are words that have two syllables.

Examples in mernyang are:

[tú/gũ] ‘push’

[tá/kát] ‘pull’

[Бú/gát] ‘tie rope’

[yu/gur] ‘ breast’

[djа/gám] ‘ jaw’

Poly syllabic

44

In polysyllabic, the words contain more than two syllables. For example

[nа/kùp/dùs] ‘snail’

CV CVC

CVC

[mаt/dz∂/dik] ‘wife’

CVC CV CVC

[Jаbаu/dɔ/gɔ/l] ‘ hard’

CVCVV CVCVC

2.3

PHRASE STRUCTURE RULES IN MERNYANG LANGUAGE

As pointed out by Yusuf (1997:6), a phrase structure rule is a set of rules which generate

the constituents of a phrase or clausal category. Lamidi (2000:66) refers to it as the rule of the

base component which inserts words into their logical positions in a structure

Horrocks, (1987:31) defines phrase structure rules as the basic component to syntax,

which are simply a formal device for representing the distribution of phrase within sentences.

Using the basic syntactic structures, then noun-phrase, verb phrase, prepositional phrase,

and adjectival phrase in mernyang language will be examined. Employing the Government and

Binding theory, the phrase structure rule of Mernyang can be exemplified using the schema

below:

CP

Spec CI

CI

CIP

IP

Spec I

II

I VP

I

Tns Agr

VP

Spec V

45

VI

V (NP) (PP)

NP

VI Spec

NI

N (Det)

2.3.1 NOUN PHRASE

According to Yusuf (1997:8); the noun phrase (NP) is the category that codes the

participants in the event or state described by the Verb. The Noun Phrase is headed by the noun

or pronoun (when it is called Noun). The head of a phrase is the single word that can stand for

the whole construction i.e. the single lexical item that can replace the whole phrase.

Mernyang language operates the head first i.e. the head of the sentence comes before

other satellites.

NP LEXICON AND SATELITES

Chíe

àmm

The

boat

NP

46

Det

Spec

NP

Chíe

NI

N

àmm

The

boat

2.3.2 VERB PHRASE

According to Yusuf (1997:21) verb phrase is traditionally called the ‘predicate’ because it

has the sentence predication namely, the verb. The verb is the head of the verb phrase (VP). It is

the lexical category that tells us what the participatory roles of the nominal’s are in the sentence

i.e. the roles of the AGENT, PATIENT, LOCATIVE, EXPERIENCER etc. The verb will also

indicate the role of such of nominal, syntactically either as subjects or objects. As the head of

the VP, it is obligatorily present with or without its satellites.

complements or adjuncts.

The formal notation for verb phrase is VP

V (NP) (PP)

Below are examples of Verb phrase in Mernyang language

Chíet com

lariem

Slap

ear

girl

Slap

the

girl

VP

47

Verb Satellites could be

VI

V

Spec

NP

Chíet

Det

NI

Com

N

Láriem

Slap

ear

girl

2.3.3 PREPOSITIONAL PHRASE

Jowitt and Nnamonis (1985:228) observe that prepositions are frequently used to form

idiomatic phrases, which function as adverbial of time, place or manner. The prepositional

phrase is headed by a preposition, which comes before a noun in mernyang.

Examples of PP in mernyang

bé’shée

Góe

Péy

At

Place School

At

the

school

PP

PI

48

P

NP

NI

Det

N

Goé

Péy

bé’shée

At

place

school

2.3.4 ADJECTIVAL PHRASE

An adjectival phrase, as pointed out by Awolaja (2002:27) does the work of an

adjective. It usually qualifies or modifies a particular noun. Lamidi (2002:73) defines it

as a phrase having an adjective as its head which can be premodified by adverbials

The phrases given below are examples of adjectival phrases in mernyang

language.

Adong’a

Very beautiful

Very beautiful

2.4.

Bìs

dógól

Bad

much

Too

bad

Lexical Categories in Mernyang

49

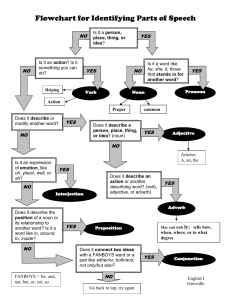

Lexical categories are what were referred to as the parts of speech in classical

grammar. The grouping of words in a language is based on function. Technically

speaking, a word does not belong to any class until it is used in a particular context. This

is because one word can perform more than one function.

For convenience, however, words are traditionally grouped into eight parts of

speech, i.e. the eight lexical categories are as follows

i.

Nouns

ii.

Pronouns

iii.

Verbs

iv.

Adverbs

v.

Adjectives

vi.

Prepositions

vii.

Conjunctions

viii.

Exclamation Interjection

These eight lexical categories will be described in respect to Mernyang language.

2.4.1.0 NOUN

Darbyshire (1967:124), A noun is a lexeme which functions typically as the head of a

nominal segment. Traditionally, a noun can be denied as a part of speech that identifies people,

places, objects, actions, qualities and ideas. From the point of view of syntactic function, we can

say that a noun is a word functioning as the subject or object of a verb e.g Tolu ate pawpaw.

These are different types of noun in Mernyang language among which are:

50

i.

Concrete noun

ii. Abstract noun

iii. Common noun

iv. Collective noun

v. Countable noun

vi. Uncountable noun

2.4.1.1 Concrete nouns

Concrete nouns are nouns that can be seen, touched & measured. Examples of concrete

noun in Mernyang are:

Lá’u

-

Bag

Mátò -

Car

Cogup -

shoe

Shiem -

Yam

2.4.1.2 Abstract Noun

Abstract noun refers to Intangible things i.e. things that cannot be seen or touched. It has

to do with feelings, emotion etc. Examples of Abstract noun in Mernyang are:

Fus

-

sun

Dàgàr -

star

Kóù

darkness

-

Dèfíl -

Anger

Ndèmpé-

Love

2.4.1.3 Common Noun

51

Common noun denote general category of things i.e. occupation or trade names of animal

Mato -

Car

2.4.1.4 Collective Noun

Nouns in this class express many members of a group in one name. they are also

sometimes called “Class Nouns’. Examples of collective nouns in Mernyang include

Béshìé -

school

2.4.1.5 Countable Noun

These are nouns that can be counted i.e. the determiner ‘a’ or ‘an’ can be used with it and

plural maker can easily be added to their singular forms. Examples in Mernyang are:

Eók

-

goat

Ļóu

-

house

A’ás

-

Egg

Jáng

-

cup

2.4.1.6 Uncountable Nouns

These are nouns that cannot be counted. They cannot be qualified by numerals or other

qualifiers. They can also not take or be used in plural. Examples in Mernyang are:

Ámp

water

Éss

sand

Píép

Air

52

Úrúng

Dust

2.4.2 Pronoun

According to Darbyshire (1967:137) A pronoun is a word which can correlate with a

noun or nominal segment. A pronoun refers to a word acting for a noun, or that can be used

instead of a noun.

Pronouns can be classified according to their use into the following types:

53

Singular

Independent

Object

Subject

Possessive

1st Person

I

Me

I

Mine

Án

án

án

ma’ án

You

You

You

Yours

Gòe

Gòe

Gòe

Gòe

He/she/it

He/she/It

He/she/It

Ńyí

Ńyí

Ńyí

Ńyí

Plural

Independent

Object

Subject

Possessive

1st Person

We

us

We

ours

Móen

Móen

Móen

Móemùn

You

You

You

Yours

Mùendúk

Mùendúk

Mùendúk

nòemak

they

their

they

theirs

móup

móup

móup

móup

2nd Person

3rd Person

2nd Person

3rd Person

Interrogative Pronouns

Amèéh

‘What’

Ámeeh uńida

‘Which’

Áwúdá

‘Who’

Ánsàbèmìé

‘Why’

Áńié

‘Where’

Ápènàá

‘When’

Áńdagánà

‘how’

54

His/hers/His

2.4.3 Verbs

The word verb can be used as a general name for the head of verbal groups. Verbs play

an important role in a sentence by linking the action that has taken place between the subject and

object i.e the one that is taking an action (Agent) and the receiver of an action (patient). We

have two classes of verbs transitive and the intransitive verb.

2.4.3.1 Transitive Verbs

Transitive verb is one that has an NP object (Yusuf, 1997:21) Examples of transitive verb

in English language.

I want the biro

‘hit’

‘kick’ etc

2.4.3.2 Intransitive Verbs

Intransitive is a type of verb that has no object NP. Examples in English are:

rise etc

Examples of verb in Menyang are:

Wágúéjí

‘come’

Sa’am

‘sleep’

Gòk

‘sick’

Spe

‘sing’

55

weep,

Mú’ań

‘go’

Líèng

‘swim’

2.4.4 Adverbs

Adegbija (1987:103) describes an adverb as a word or group of words that describes or

adds to the meaning of a verb, an adjective, another adverb or a whole sentence. Examples of

adverbs in mernyang are:

Borbor

‘quickly’

Túpfíl

‘Angrily’

Lélé

‘slowly’

2.4.5 Adjectives

Adjectives belong to the part of speech whose members qualify nouns (Adegbija,

1987:100)

Examples in mernyang language include

Mùgà’àl

‘sat’

Kwàsí

‘old’

U’fáo

‘New’

2.4.6 Preposition

56

Preposition relates a noun to a verb in terms of location, direction, state, condition etc. (Yusuf,

1997:97). Examples in Mernyang language are shown below:

Gòe-pé

‘at’

Gòenùk

‘behind’

Ndíng

‘before’

Bùdér

‘under’

Ńdígúen

‘inside’

2.4.7. Interjections

An interjection, according to Adegbija (1987:108), is a word that expresses emotion.

Examples of interjections in mernyang include:

Bóù!

‘Ah!’

Awufó’à!

‘eh!’

2.4.8. Conjunctions

A conjunction is a word that joins words, phrases, clauses or sentences (Adegbija,

1987:106). Below are some examples of conjunction in Mernyang Language.

Góè

‘and’

57

2.5.

BASIC WORD ORDER IN MERNYANG

Ayodele (1999:51) describes basic word-order as the permissible sequence or

arrangement of lexical items to form meaningful and grammatical sentences in a language. The

idea of basic word-order stemmed from the fact that languages need to be classified on the basis

of how syntactic constituents, such as subject, verb and object, are structured in a simple,

declarative active basic sentence. Universally, six syntactic types have been identified to be

employed by languages. They are (Yusuf, 1998:35):

Subject

-

Verb

-

Object (SVO)

Subject

-

Object

-

Verb

Object

-

Verb

-

Subject (OVS)

Verb

-

Subject

-

Object (VSO)

Verb

-

Object

-

Subject (VOS)

Object

-

Subject

-

Verb

(SOV)

(OSV)

Mernyang language is an SVO language, that is in Mernyang simple declarative sentence,

the subject comes first, followed by the verb and the object.

S

V

O

Sumnóe

a’

shehu

My name

is

shehu

My name

is

shehu

58

Mariam

tát

ball

Mariam

kick

ball

Mariam

kicked the ball

2.6.

Sentence Types in Mernyang language

A sentence is the largest grammatical or syntactic unit onto which rules apply (Adegbija,

1987:87). A sentence has also been described as a group of word which make a statement a

command expresses a wish, ask a question, or make an exclamation (Yusuf, 1998: 101)

A sentence is defined as a group that begins with a capital letter and ends with a full stop, a

group of words which makes a single complete statement and contains a verb (Akere; 1990:65).

In the conventional treatment of sentence, (Yusuf 1998:66), says there is favoring of sentence

types; hence there are structural types and semantic types.

The semantic types are: Declarative, Interrogative, Imperative and Exclamatory. Along

the structural dimension, we have simple, compound and complex sentences.

Three sentence types were identified in Mernyang language. These are simple, compound and

complex sentences.

59

2.6.1 Simple Sentence

A simple sentence is a sentence that containing only one finite verb (Adegbija, 1987:89).

It is made up of one NP – subject and a predicate. Below are examples of the simple sentence in

Mernyang language.

S

N

O

Sumnóe

a’

shehu

My name

is

shehu

My name

is

shehu

Nàpá

Tóe

kúng

She

kill

leopard

She

killed

the leopard

2.6.2 Compound sentence

As pointed out by Yusuf (1997:61) a compound sentence is formed when two or more

simple sentences are conjoined by a coordinating conjunction. A compound sentence can also be

described as the combination of either two or more verb phrases (VPS) or sentences through the

use of a lexical category called conjunction. Examples of compound sentence in Mernyang

language is shown below:

Abu

Tòngná’á gírgì yíl,

ńsà m’bes wil m’o’u

60

Abu

waiting train,

but

late

Abu waited for the train, but the train was late

Musa Síé dàshùk góe to’ok compée

Musa eat pounded yam with soup vegetable

Musa ate pounded yam with vegetable soup

2.6.3 Complex sentence

According to Yusuf (1997:63) a complex sentence has a sentence embedded in one of the

phrasal categories VP or NP as the main clause and a number of surbodinate clauses. Examples

from Meryang are:

Habu móp góe Ali Múwak gòè pang gòènùk béshìé

Habu them Ali

go

home back

school

Habu and Ali went home after they finished studying

Dapo síe beshie/ góèfé ńsa shíé-bèshìé góeńát

Dapo pass exam his because he read well

Dapo passed his exam because he read well

2.7.

Functional classification of sentences in Mernyang

This section examines the functions that sentences perform in Mernyang language. On

the basis of this, Meryang sentences can functionally be classified as:

61

i.

ii.

iii.

iv.

Declarative Sentence

Imperative Sentence

Interrogative sentence

Exclamatory sentence

2.7.1. Declarative Sentence

Declarative sentences are statements.

They normally assert the truth of a thing.

(Adedimeji and Alabi, 2003:55). In Mernyang their subjects precede their respective predicates.

Examples in Mernyang language include.

Mope á

Wát

Mope is thief

‘Mope is a thief’

A máàn

mó’u

I know don’t

I don’t know

Zuberu á wú már

Zuberu is farmer

Zuberu is a farmer

2.7.2 Interrogative Sentence

An interrogative sentence is used to make an enquiry or ask questions which demand

some sort of response from the addressee. However, it could be rhetorical (Adedimeji and Alabi,

2003:55). Example in mernyang is shown below:

62

Goè ánèe

You where

Where are you?

2.7.3 Imperative sentence

This is used to express a command or make a request (Adedimeji and Alabi, 2003:56)

Example in meryang is shown below:

Wágòéjè!

‘Come!’

Mù’án

‘go!’

2.7.4 Exclamatory sentence

Exclamatory sentences express strong feelings of surprise

2003:54) Example in mernyang are:

Áwúdà!

‘Who !’

Ápènáà !

‘When !’

63

(Adedimeji and Alabi,

CHAPTER THREE

3

3.1

QUESTION FORMATION IN MERNYANG

INTRODUCTION

Having gone through the syntactic concepts of the language under study, the next thing is

to examine the various ways in which questions can be formed in Mernyang language.

Questions are primarily used to express lack of information on a specific point and to

request the listener to supply this information. Naturally, a question is asked in order to get more

facts about a particular thing.

(Radford1981:46) explains further that questions in national languages can be classified into a

number of types.

(Dillon 1986:136) defines question formation as a verbal form from which the question in mind

is crushed generally with language. According to him, the person who forms or ask question

emphasizes and communicates some attitudes.

Various types of questions will be discussed in this chapter. They are WH question, Yes or No

question, Echo question, Alternative question and Tag question.

3.2

The WH question in Mernyang

WH-question is also called content – word question that is, one is requiring for particular

information about a particular thing, unlike the Yes/No question which only requires a Yes/No

64

answer. The WH question starts with “WH” word like – What, Where, Who, When, Which,

What etc.

Any part of the sentence constituent can be questioned ‘who’ will ask for information about the

particular identity of a person, ‘what’ will question the verb i.e. action, ‘why’ will question the

reason for an action, “which” will question the present option, ‘where’ will question the time of

occurrence.

The WH-question makers in mernyang are:

Ámie

‘What’

Awuda

‘Who’

Anśa bèmìe

‘why’

Amie wuda

‘which’

Ánìé

‘where’

Ańdagánà

‘how’

Ápènáà

‘when’

Ánìé

Ánìé ‘where’ is one of the WH question maker that seeks to know ‘location’. It questions the

object NP of a sentence e.g. The boy is in the class

Where is the boy?

Example in mernyang

2.a)

Habu mù’án njos

Habu go jos

Habu travelled to Jos

65

2.b)

Habu mù’án

Ánìé

Habu go where

Where did Abu travel to

Awuda

Awuda “who’ is a WH question maker, which seeks to know the doer of an action .i.e. it

questions the subject NP of a sentence. E.g.

The boy ate the food

Who ate the food?

In mernyang “Awuda”, also seeks to know the doer of an action in a sentence. Example in

mernyang

1.a

Sherima chiet síe nánie

Sherima cook food (Det)

Shemia cooked the food

1.b

Awuda chiet sié nanìé

Who cook food (Det)

Who cooked the food?

Ámìé Wúdà

Ámìé Wúdà ‘why’ wants to know the ‘reason’ for an action performed in a sentence i.e. it

questions the verb in a sentence e.g. I travelled by air

Why did you travel by air?

Ámìé

Ámìé ‘What’ asks for a particular thing in the sentence. It usually question the object Np in the

sentence e.g. I hate houseflies

What do you hate?

In mernyang, it also functions as asking for a particular thing. Examples of Ámìé in

Mernyang are

66

1a.

Musa wát biyat

Musa steal cloth

Musa stole clothe

1b.

Musa wát á bémiè’é

Musa steal what

What did Musa steal?

Ápènáà

Ápènáà

‘When’, as a WH-question maker, questions the ‘time’ an event too place in a sentence, for

example

I travelled yesterday

When did you travel?

In mernyang language, Ápènáà ‘when’ is used to ask/denote when a particular event took

place. Examples in mernyang

1a.

Habu goe wul/chínee

Habu will come today

Habu will arrive today

1b.

Habu goé wul apèná’à

Habu will come whenQM(AGR)

When will Habu come

Amíe wúdà

Given options, Amíe wúdà ‘which’, seeks to know a particular thing or person in a sentence i.e

.specification. It questions the subject NP of a sentence. For example

The girls are my friends

Which of them is your friend?

67

IP

II

Spec

NP

I

NI

VP

Spec

Habu

VI

V

NP

Mu’an njos

IP

II

Spec

NP

NI

I

VP

Spec

VI

N

V

NP

Habu

Mu’an NI

Habu

go

N

CP

CI

C

Anie

Where

68

IP

II

Spec

NP

I

NI

VP

VI

Spec

N

V

NP

sherima

N

Det

chiet síe

naníè

cook food det

CP

CI

Spec

C

QM

IP

I

VP

awuda Tns agr Spec

Who (past)

VI

V

NP

chíet N

sie

cook food

Who cook the food?

Who cooked the food

69

Det

nanìé

(det)

IP

II

Spec

NP

NI

I

VP

Tns Agr Spec

VI

N (Past)

V

NP

Musa

w’at

NI

Steal

N

Biyat

Cloth

Musa steal cloth

Musa stole cloth

IP

II

Spec

NP

NI

I

Tns Agr Spec

VP

VI

N

V

Musa

w’at

Steal

NP

NI

N

CP

CI

C

Bemie’e

Musa steal what?

What did Musa steal?

70

3.3

Yes/No Question in Mernyang

A yes-no question formally known as a polar question is a question whose expected

answer is either, “Yes” “No”. Formally, they present an exclusive disjunction, a pair of which

only one is acceptable in the English language such questions can be formed in both positive and

negative forms. E.g. Will you be here tomorrow’ and

“Won’t you be here tomorrow”

Yes/No questions are in contrast with non-polar WH questions, with the five WS. Which

do not necessarily present a range of alternative answers, or necessarily restrict that range to two

alternatives.

In some languages, a yes/no question is formally distinguished by features, such as:

Rising sentence – final intonation

A sentence – initial or sentence – final particle

Verb morphology

A difference of word order, such as the placement of the verb closer to the beginning of

the sentence than in the declarative sentence and

An Interrogative clitic that attaches to the item in the sentence that is being questioned.

Examples of Yes/No question in Mernyang

1. Nde góegoe kogup a’a

Do you have shoe QM (AGR)

Do you have a shoe?

2. Gòe dém Solomon a’a

You love Solomon QM (AGR)

Do you love Solomon?

71

3. Dè dém síe à’à

Does he like food QM

Does he like Food?

4. Ndé Stephen Yágóe wúl a’a

Will Stephen AGR come QM (AGR)

Will Stephen Come?

CP

CI

Spec

C

IP

II

Spec

I VP

Nde

Do

NP

Spec

PRN

V

V

goe

NP

goe

you

N

spec

have shoe

QM

aa

Do you have a shoe?

IP

II

Spec

NP

PRON

Góe

I

VP

Spec VI

V

NP

dem N

spec

Solomon

QM

aa

Do you love Solomon?

72

3.4

ECHO QUESTION IN MERNYANG

According to Radford (1988:463) “echo questions are so called because, they involve one person

echoing the speech of another person in a dialogue’’. Echo question involves what has been said.

It also involves echoing the speech of someone i.e. a reaction of someone’s speech. Echo

question can be classified into WH-echo question, which involves the use of WH marker e.g.

The boy lives where? And Yes –no-echo question, which requires a Yes/No answer, and there is

no re-ordering.

e.g

I bought a house

You bought a house?

Haegman (1991:302) says, echo question is used as a reaction to a sentence by a speaker who

wishes the interlocutor to repeat the sentence or part of it. It is simply formed by substituting a

question word for constituents.

Generally, if the hearer does not quite catch all of a speaker’s utterance, the hearer may ‘echo’

the speaker’s utterance replacing the unclear portion(s) with an interrogative.

Thus, ‘Did John see what?

might be a response to ‘Did John see (unclear) .i.e. the sentence is

not clear. Examples of echo question in mernyang are:

1a.

Speaker

Á

síét

mátò

I

buy

car

I

1b.

A

bought a Car

Speaker

Gòe

You

B

Síet mátò ‘àà

buy Car

QM

73

You bought a car?

2a.

2b.

Á

síet

mátò

I

buy

Car

I

bought a car

Gòe síet á bé mìé

You

buy what?

You bought what?

3a.

Die Góe síet mátò, àà

Will you buy car QM

Will you buy a car?

3b.

Díe yágà síet mátò àà

Will (he/she) buy car QM

Will I buy a car?

4a.

Gòe swá’á àm gòe nòe mó’u

You drink water mine no

Don’t drink my water

4b.

Goe yoúng á swá’á á mìé goé goe mó’u’é

You said

drink

what your no

Don’t drink your water?

IP

Spec

NP

II

Tns (pst)

NI

VP

VI

PRON

V

NP

A

siét

NI

I

buy

N

Mátò

Car

I bought a Car

74

IP

II

Spec

NP

I

VP

PRN

Tns (pst) VI

Góe

V

You

siét

NP

NI

Buy N

Mato

Car

CP

Spec

aa

QM

You bought a car?

3.5

ALTERNATIVE QUESTION IN MERNYANG

In alternative questions, conjunction ‘or’ is used to link up the proferred alternative(s) in the

sentence. This type of question, gives the listener options from which he/she makes a choice.

Qurik (1972:399) defined alternative questions as the pre or two or more alternative(s)

mentioned in the question for example, will you take cake or bread?

Dillion (1986: 139) defined alternative question as a generic form that specifies ideas of

two alternative words to choose from.

Another example in English is”will you like black or white?’’ This question contains a

separate nucleus for each alternatives; arise that the list is complete. The listener is then left to

make his choice.

75

Examples in mernyang

Díe mú máng á mátò, à,à búsíng yánge’e

QM we carry

car

or a

bicycle

Shall we take car or bicycle?

Goe síe síe mie wùdá góe síe moon kappa á’á trémí a’a shem’e

Food which you

Tuwo

rice

or beans or yam

Which food will you eat, would you eat Tuwo, Beans or Yam?

Yagóe múan Ogechi beshie a’a sa’am

Will go

Ogechi School or sleep

Will Ogechi go to school or sleep?

3.6

TAG QUESTION IN MERNYANG

A further type of question, which involves positive/negative orientation is the ‘tag question’

attached to a statement e.g . (1) The boat has already left, hasn’t it?

(2) You are not throwing these books away, are you?

According to crystal (1987:423), “a tag question is a way of confirmation of a statement, which

has the fore exclamation than genuine question?

Tag question is a string usually consisting of an auxiliary and a pronoun, which is added at the

end of a sentence. Tag question is used to ask for confirmation whether something is true, or

not, by making a statement in a delightful mind.

76

Thus, the expression could be negative/positive. There must be a definite pronoun in the tag, and

this pronoun, must agree with the subject of the main clause. Examples in mernyang are:

Dęm, làlà múp, Áa dęm mó’u’é

Like child his like, no yes?

He likes his child, doesn’t he?

Àn jééta na’a góe mòue, àa a’na’a

goe’è

I never see you no or have I seen you

I have never seen you before, have I?

Ùgòun neogèon mòu, Ùgòun neogèùn à’á

Hot

there is no

hot there is Qm?

It is hot, is it?

3.7

RHETORICAL QUESTION IN MERNYANG

Rhetorical question is the last question that would be discussed in this chapter.

Rhetorical question is interrogative instructor, and has the force of a strong assertion and does

not require any answer.

Crystal (1987:212) says, rhetorical question is a type of question, which has normal rising

information of yes/no question, but is chiefly distinguished by the range of pitch movement. It

functions as a forceful statement. More precisely, a positive rhetorical question is like a strong

positive one.

77

Baker (1989:``112) states that rhetorical question is a question which does not expect an answer.

Since it really assets something which is known to be expressed cannot be denied.

Quirk (1972:829) says rhetorical question is interrogative in structure but has the force of a

strong assertion. It generally does not expect an answer.

POSITIVE

:

Is that a reason for despair?

(Surely not ……………………….)

NEGATIVE

Is no one going to define me?

(Surely someone will

There is also a rhetorical WH question which is equivalent to a statement in which the question

element is replaced by a negative element e.g. nobody cares. One fact about the rhetorical

question is that it does not require a concrete response.

surprising situation.

Examples in Mernyang

Àwúdà wúl már góe mú’e

Who come farm ours

Who came to our farm?

Gòe má’án bìe wú níe góe wá’à

You know what he become QM

Do you know what he can become?

78

The question is controlled by a

Àwùdá má’an píe wú yíl gòe mù’án’e

Who know place where world go?

Who knows where the world is going to?

Àwùdá góe e’ep bout mùgó góe wálla gòe yílèé

Who will deliver someone from suffering world?

Who will deliver someone from the suffering of this world?

79

CHAPTER FOUR

4.0

TRANSFORMATIONAL PROCESSES IN MERNYANG

4.1

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will treat various transformational processes attested in Mernyang

language. These transformational processes include Focus construction, relativization

and reflexivization. In the course of the analysis of the study, these processes will be

discussed with relevant examples as illustrations as it is attested in the language of

study.

Radford (1988:401) asserts that, the two levels of (D-structure and S-structure)

are inter-related by a set of movement rules known technologically as move-alpha).

This is simplified below to exemplify the relationship between the two levels.

Base

D-structure

Move alpha (transformation)

S-structure

4.2

Focus Construction

According to stockwell (1997:157) focus sentences are derived from basic

sentences. Focus introduces special marking into surface to set off some element(s)

as important.

Focusing is a universal syntactic process among human language which entails

definiteness and emphasize. A speaker pragmatically assigns prominence to a part of

80

his/her message that he/she wishes or want to emphasize without necessarily

changing the substance of the message. Focus sentences are derived from basic

sentence. Examples of focus construction in mernyang include the following?

BASIC FORM

Musa sìet léu èn shehu

Musa buy house for shehu

Musa bought house for Shehu

Subject – NP focus

Á Musa siet léu shén shehu

Is Musa buy house for Shehu

It is Musa that bought house for shehu

Direct Object -NP focus

A léu Musa síét shén Shehu

Foc is house Musa buy give Shehu

It is house that Musa bought for shehu

81

IP

Spec

I̒

I

VP

NP

TNs

Spec

NI

PRSNT

ǿ

VI

ASP Spec

V

N

NP

NI

Spec

Musa

N

Siet

ǿ

PP

PI

spec

léu

P

Q

en

NP

spec

ǿ

NI

N

shehu

Musa sìet leúèn shuhu

Musa buy house for Shehu

Musa bought house for Shehu

Basic Form

Funmi ásíe ásskòó

Funmi eat egg

Funmi ate egg

82

Direct object – NP focusing

Á ásskòó funmi

síé

Its egg funmi eat

It is egg that Funmi ate

Subject NP focusing

A Funmi síè àsskòó

Is Funmi eat egg

It is Funmi that ate the egg

4.3

Relativization

A relative clause could be a sentence embedded in surface structures as modifier

of an NP, the embedded in sentence having within WH pronominal replacement for a

deep structure.

Relativization is a syntactic process which is used to show and make a sentence

more apt and more meaningful. It prevents unnecessary repetition, which can bring

about confusion, through the introduction of the relative marker (who, which, that

etc.) The relative marker have antecedent that is related to the NP head.

According to Yusuf, (1997:100), relative embedded sentence modifying an NP

(noun phrase) as added (adjuncts) information. In Mernyang, relativization is an

important aspect of transformational process because it makes reference to certain