Parker and Pollock

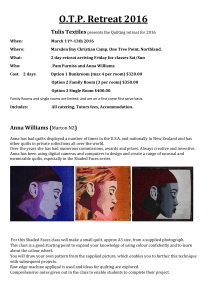

advertisement

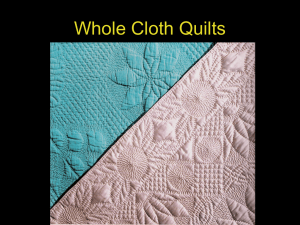

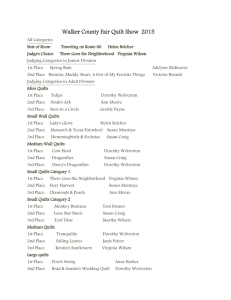

Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock “Crafty Women and the Hierarchy of the Arts” in Korsmeyer 1) Sex of the artist conditions the way art is seen and discussed. a) Art history: organizes art based on a system of values leading to a hierarchy of forms. b) Painting and sculpture vs. arts that adorn people, homes, utensils, as applied, decorative. c) The latter are attributed lesser intellectual effort or appeal. 2) Division of art forms into arts and crafts in Renaissance: changes in art education from workshops to academies. a) William Morris: cannot sever great arts from the Decorative Arts i) When they are parted it is bad for the Arts in general: the lesser ones become trivial, incapable of resisting fashion; and the greater will become adjuncts to pomp or toys of the rich 3) The history of flower painting: link between sex and status a) Women’s presence in an art form changes its status, i.e. since the 17th century in Holland. b) It became a common art genre for women artists. c) Classified as pretty, painstaking, petty. d) The social definition of femininity affects the evaluation of what women do. e) Legrange in 1860 thought women should stick with painting flowers: a good fit. f) Tendency to identify women with nature. g) The painting becomes solely an extension of womanliness and the artist a woman fulfilling her nature. h) This removes these paintings from fine art. 4) Feminist historians react by valuing women’s work in the crafts. a) Some have hailed embroidery and needlework. b) Mainardi: put their creativity into needlework arts which are a universal female art form c) But this does not displace the hierarchy of values in art history. d) A social definition of women arose with the emergence of the separation of art and craft. 5) English embroidery became a feminine craft. We need to avoid the trap that ensnared Victorian historians of needlework. a) Elizabeth Stone in 1840 link between sex and craft that sanctioned hours of work by women. b) Lady Marion Alford: inherent in the nature of English women c) Even today the vast majority of embroidery workers are women. 6) But it has not always been exclusively female. a) In medieval times both monks and nuns did it, and queens had household workshops. b) It served the function of glorification of institutions. 7) In the 13th and 14th centuries we have the style of Opus Anglicanum and an expanding market a) Male-controlled guild workshops. 8) But in the Elizabethan era women’s relationship to it changed [again]. a) Ecclesiastical embroidery was victim of Reformation, but there was greater demand for domestic embroidery. b) Broderers Guild in 1568: all men…. all amateurs were women. 9) Embroidery was a proof of gentility: this “women’s work” helped maintain class position a) Decoration of surfaces suggested refined, tasteful life. b) Hours of embroidering symbolized tireless industry etc. 10) 11) 12) 13) 14) 15) 16) 17) 18) 19) c) Lady Mary Wortley Montague: woman should know how to use a needle Needlework began to embody a feminine stereotype. a) Addison: delightful entertainment for women, and it keeps them from scandal. Needlework was both decorative and utilitarian. a) Some attacked it as misplaced economy and in 1810 blamed it for women’s general ignorance. By late eighteenth century synonymous with femininity. a) Samplers were exemplars until 1523 and then became educative for young girls. b) Late 18th century ones were naïve and technically limited. c) It was to display femininity Although beautiful samplers represent a female childhood structured for feminine characteristics. a) Patience, submissiveness, service, obedience, modesty taught. If samplers are valued today it is for nostalgic reasons or manual dexterity. a) Embroidery was only acknowledged as an art form when it copied art prints or paintings. b) Mary Linwood in 1798 was a needlepainter: seen to exemplify force and energy of the female mind and awakened the art that gave birth to painting. Prehistoric forms of craft were in 1925 by Hoernes and Menghin seen as feminine: the geometric style, as domestic, external decorativeness a) Moving some abstract geometric art from folk museum to fine art museum: revealing transformations. b) Navaho blankets in museums in the 1970s: those who wished to see them as art had to expunge craft association. c) Ralph Pomeroy: forget in order to really see them as Art, look at them as paintings, by several nameless masters of abstract art. They become abstract paintings and the women become nameless masters. a) Status of art work is tied to status of the maker. b) The monograph is on a named artist, whereas books of craft history are more concerned with objects. c) Pomeroy uses “nameless masters” which is used for artists whose names have been lost. d) Calls them nameless masters not mistresses or artists: the fine artist is a male: change of sex and race. Status of the artist depends on sex: why would women’s activities in the home be given lower status? a) Feminist anthropologists: Levi-Strauss, status depends on place on a symbolic scale from Nature to Culture. i) Humans transform raw materials into tools, houses, clothes: cultural artifacts. ii) Sherry Ortner: roles of women are perceived as occupying a place between Nature and Culture, as bearing children they are Nature, but as educators they are Culture. iii) These things are done in the home. iv) Cooking is usually women’s work: nature to culture, but when a culture develops a haute cuisine the high chefs are almost always men: when culture reaches a higher level it is restricted to men The work is given secondary status based on the place performed: domestic. What distinguishes art from craft is mainly where made, in home or… a) Craft could be defined as domestic art. 20) What is need for transformation of Indian weaving into accepted definitions of art. 21) In the books on it the fat that they were made by women is easily overlooked. a) Formal element in quilts as reason for their recognition as art. 22) Quilts: Dedicated to the anonymous women: suggests they are not represented in their work. a) Women are reduced to skilled hands and eyes. b) Quilts were not made anonymously: frequently signed. 23) Patchwork quilts objects of great beauty yet the names often led to dismissal of quilt making as mere repetition of pattern. 24) One type “log Cabin”: quilts in this style are varied, the decisive role of the individual quilt-maker is effaced: Carlton Safford and Robert Bishop: they had a way of creating their own patterns. 25) Recognition of quilts as art achieved by spotlighting objects in isolation from their production. a) Connection with traditional notions of craft might get in way. 26) The conditions of production of quilts provide a basis for radical critique of art history. 27) Personal, political, religious and social meetings sewn into the quilts: a) Evolved an abstract language to signify their joys and sorrows etc. b) When appreciated as decorations or abstract designs rather than as structures of abstract symbols their language is suppressed. 28) Skill with needle was necessary for full membership in quilting community. a) The collective part of the process used wrongly to argue that quilts are not artistically significant. b) Quilting bee was also place of meeting and had political importance as in the suffrage movement. c) In some ways the relations of quilting are richer then the relations of high art. d) Usefulness and aesthetic sensibility coincide, work and art come together. e) The specific history of women is effaced by art historical discourse categories. 29) The endless assertion of a feminine stereotype etc. in art history needed to provide an opposite against which male art can find meaning and sustain dominance. 30) Ideology works unconsciously, is inscribed into the very language of art.