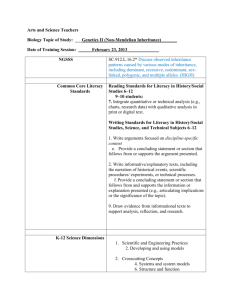

Knowledge Inheritance, Vertical Integration, and

advertisement