Rood & Riddle is a world renowned equine hospital situated

advertisement

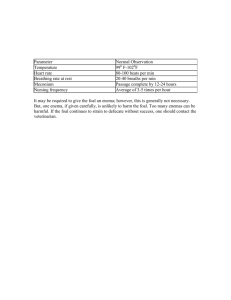

British Equine Veterinary Association Queen Mother Student Travel Award Report 2012 Phoebe Parker Rood & Riddle Equine Hospital, Kentucky USA I am hugely grateful to the BEVA Queen Mother Student Travel Award (QMSTA) for giving me the opportunity to travel Rood & Riddle Equine hospital in Kentucky to undertake a three week externship during February and March 2012. Throughout my clinical years at RVC I have always been interested in pursuing a career in the Equine field after graduation. I was considering whether to apply for an Internship after I graduated and had undertaken an externship in the UK to give me a feel for the roles of an Intern. I wanted the opportunity to witness equine practice in America and compare it to UK practice and also see if I would like to apply for an Internship after graduating. I was particularly interested in medicine, diagnostic imaging and lameness investigations. Rood & Riddle is a world renowned equine hospital situated in Kentucky, USA. Rood & Riddle has a surgery, internal medicine, advanced diagnostic imaging, reproduction and podiatry service. The hospital has two surgery facilities with five theatres between them, two of which are clean, a colic theatre and two additional supporting theatres. Whilst at Rood & Riddle, I spent time with the surgery, medicine and ambulatory services. Throughout my stay I was also on-call for emergencies that were referred to the hospital. The majority of horses seen at Rood & Riddle are racing thoroughbreds. Although it wasn’t the racing season whilst I was there, farms were prepping yearlings for the yearling sales that take place in Lexington in September. Survey radiographs screen for the presence of osteochondrosis dessicans (OCD) lesions, if present lesions are subsequently removed via arthroscopy. Hence whilst I was at Rood & Riddle I often helped to take the survey radiographs out on the farms and then read the radiographs back at the clinic. This has greatly improved my ability to read radiographs, identify the commonest sites of OCD overall as well as the commonest sites within each joint. During my visit at Rood & Riddle I saw several horses that presented with upper airway disorders. Most of these horses had disorders resulting from abnormal arytenoid movement and I ultrasonography of the larynx performed to assist in the diagnosing these disorders. I found this very interesting as I had never seen ultrasonography of the larynx used to diagnose upper airway conditions. Laryngeal ultrasonography is especially helpful where a dynamic endoscopic examination cannot be performed; hence it has the potential to be a very useful diagnostic tool in general practice. Abnormal arytenoid movement maybe caused by recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, arytenoid chondritis and laryngeal dysplasia (congenital malformation of the larynx). Recurrent laryngeal neuropathy results in denervation atrophy and loss of function of muscles (cricoarytenoideus dorsalis, cricoarytenoideus lateralis, transverse arytenoideus, vocalis and ventricularis muscles) innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Clinically Phoebe Parker QMSTA Report 2012 recurrent laryngeal neuropathy manifests as decreased or absent arytenoid abduction commonly affecting the left arytenoid more than the right. Ultrasonographically the denervated muscle becomes homogenous and hyperechoic in appearance. On ultrasonographic examination of the larynx these changes can be seen in the cricoarytenoideus dorsalis (CAD) and cricoarytenoideus lateralis (CAL) muscles. The transducer is held in transverse and dorsal planes to allow examination of the lateral aspect of the larynx. Below is a dorsal plane ultrasound image of the left and right CAL muscle. The normal muscle is on the right, the left cricoarytenoideus lateralis is denervated due to recurrent laryngeal neuropathy, and the muscle has a hyperechoic and homogenous appearance. Thyroid Cartilage Cricoid cartilage Dorsal plane ultrasound image of left and right CAL muscle of the same horse. The left CAL muscle is hyperechoic and homogenous in appearance, the muscle has been denervated due to recurrent laryngeal neuropathy. Whilst at Rood & Riddle it was the foaling season and I saw routine neonatal foal checks as well as observing the neonatal medicine services provided by the clinic and the ambulatory vets in the field. During my visit I saw foals that presented with fractured ribs that were repaired surgically, sepsis, perinatal asyphyxia syndrome and a foal with a ruptured bladder. Prior to visiting Rood & Riddle I had no previous exposure to neonatology and over the course of my three week visit I have gained a better understanding of the importance of neonatal foal checks, assessing the neonate and common neonatal diseases. This experience has been an invaluable Phoebe Parker QMSTA Report 2012 insight into neonatology and I hope to build on this after I graduate. Below is a report of a case that I found particularly interesting. Case 1 A 24 hour thoroughbred filly foal, presented with colic signs a couple of hours previously. On arrival the filly was bright, had a heart rate of 120 bpm with strong peripheral pulses, and injected bright pink mucous membranes with CRT 2-3s, right sclera diffusely injected. Respiratory rate was 44 bpm, on auscultation of the lungs, harsh lung sounds were heard. There was moderate to severe abdominal distension. The foal was sedated with a combination of opioids (butorphanol) and benzodiazepines (diazepam) and nebulised with O2 and a catheter placed and blood taken for CBC, creatinine and electrolyte analysis. Ultrasonography of the abdomen revealed free abdominal fluid and a small bladder. On electrolyte analysis the foal had hyperkalemia (K+ = 7.3 mmol/L , reference range 24 hour foal 3.6 – 5.6 mmol/L), lactate was 3.8mmol/L, hyponatremia and hypochloremia. Creatinine levels within the peritoneal fluid were greater than serum confirming peritoneal fluid to be urine. The aim of initial therapy is to stabilize the patient, correct electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities and provide fluid volume replacement in preparation for surgery to repair the ruptured bladder. Intravenous fluid therapy was commenced; a fluid bolus of 1L NaCL with 50 ml calcium gluconate was administered at a fast rate. Calcium gluconate acts as a cardiac protectant against arrhythmias caused by hyperkalemia. Abdominal ultrasounds was performed and revealed a small bladder with excess anechoic fluid within the abdominal cavity. Small bladder Excess anechoic fluid within the peritoneal cavity Abdominal ultrasound revealed a small bladder and excess anechoic fluid in the peritoneal cavity. It is important to remove the urine within the peritoneum and in doing so this will help to decrease potassium levels in the serum. The foal was induced with xylazine, ketamine and diazepam and a 10G catheter used to perform abdominocentesis, 3L of urine was removed from the peritoneal cavity, K+ was re-measured and had decreased to 5.8 mmol/L. and . After the initial 1L of NaCL fluid was administered (avoid lactated ringers solution as this is supplemented with K+) a second litre was administered with 50ml calcium gluconate and 0.5g/kg dextrose (50%) added to the fluids. Dextrose acts to drive K+ back into the cells (epinephrine and insulin can also be added to the fluid therapy to drive K+ back into the cells). As the K+ levels had been reduced and a considerable amount of urine removed from peritoneal Phoebe Parker QMSTA Report 2012 cavity the foal was taken to surgery for repair of the ruptured bladder. During surgery a dorsal wall rupture was discovered and repaired. A foley catheter was placed and this was left in place post-operatively to avoid stranguria. Whilst in place the catheter was checked every 15 minutes that it was not blocked (monitor for urine dripping from catheter) and that hematuria improved post-surgery. The foal was placed on Phenazopyridine PO q8 (4-5 mg/kg) to reduce urethral inflammation whilst catheterised. Antimicrobial therapy consisted of Cephalosporin (ceftiofur) 10mg/kg IV q12, Flunixin meglumine IV 1.1mg/kg q12 was administered for analgesia. Omeprazole PO q24 administered whilst NSAIDs and antimicrobial therapy administered. The foal was monitored for signs of colic and that she continued to nurse and PCV/TP was checked every 2 hours. Abdominal ultrasound was repeated at 3 days post-surgery and there was no free peritoneal fluid. The foley catheter was removed and the foal discharged at 5 days post-surgery. The second interesting case that I saw during my visit was seen whilst observing one of the surgeons specialising in respiratory surgery. Case 2 A 2 year old Morgan mare presented with a several month history of bilateral mucopurulent nasal discharge, with an occasional cough. The nasal discharge was unresponsive to Potentiated Sulphonamides. No other horse on the yard was affected. On physical examination temperature, pulse and respiratory rates (TPR) were within normal limits. There was nothing heard on auscultation of the lung fields and the nasal discharged had no foul smell to it which would be indicative of a tooth root abscess. On radiology of the sinuses there was no fluid line present and therefore no evidence of sinusitis. On endoscopy the gutteral pouches were clean but there was mucopurulent material within the trachea. A tracheal wash was obtained and sent for cytology and culture and sensitivity. Thoracic radiographs were generally unremarkable. On thoracic ultrasound there was thick fluid identified within the pleural cavity, the right cranial ventral pleural cavity was worse than left. The evidence was suggestive of bacterial pleuritis or pleuropneumonia. Lung lobe Thick fluid within the pleural cavity Ultrasound image of the right cranial pleural cavity illustrating the right cranial lung lobe floating in thick pleural fluid. Phoebe Parker QMSTA Report 2012 Bacterial colonisation of pulmonary parenchyma results in exudative fluid accumulation within the pleural space in response to inflammation and infection. Large amounts of fluid containing bacteria, neutrophils, fibrin and cellular debris accumulate. Bacterial colonisation may result in pneumonia or pulmonary abscess formation. Extension of the infection and inflammation to the pleural space results in pleuritis or pleuropneumonia. The commonest causative organism is Streptococcus Zooepidemicus and other beta-haemolytic Streptococcus Spp. Which can be complicated with infection by Gram negative bacteria such as Pasturella, E-coli, Enterobacter, Klebisella and Pseudomonas Spp. Anaerobes such as Bacterioides Spp and Clostridium Spp may be identified but are less common. Pleuropneumonia can occur spontaneously but some common risk factors include recent transportation, viral infection, esophageal obstruction or general anaesthetic. Early signs may include pyrexia, depression, increased respiratory rate with a shallow breathing pattern, exercise intolerance, nasal discharge and intermittent cough. Other clinical signs maybe weight loss, sternal/limb oedema and gait stiffness, horses may stand with elbows abducted due to pleural pain. Chronic disease results in intermittent pyrexia, weight loss and exercise intolerance. The mare was put on Potassium Penicillin IV at a dose of 22,000 IU/kg q6 and Gentamicin 6.6 mg/kg q24 whilst waiting for the bacterial isolate to be identified. The mare was also nebulised with 1g Ceftiofur BID q12 and TPR monitored every 2 hours. Throughout hospitalisation TPR remained within normal limits and no abnormalities detected on thoracic auscultation. The bilateral nasal discharge began to resolve over a 3 day period although she still had an occasional cough. Cytology report of the tracheal wash reported there were few epithelial cells, neutrophils too numerous to count, a few erythrocytes, cocci and light debris. The isolated bacteria were identified as Streptococcus Zooepidemicus. A repeat ultrasound scan of thorax after 5 days on Penicillin and Gentamicin showed a mild improvement of fluid within pleural cavity. The nasal discharge continued to improve. After one week of Penicillin and Gentamicin IV therapy the mare was discharged on box rest and Chloramphenicol and be rechecked in 2 weeks. With regards to treating pleuropneumonia, long term therapy is often necessary to clear up all the bacterial infection within the lungs and pleural cavity. I have decided that I would like to go straight into equine general practice when I graduate, however I haven’t ruled out applying for an Internship after a period of time in practice. I found my three week externship at Rood & Riddle very inspirational and particularly enjoyed neonatal medicine, prior to visiting Rood & Riddle I had no experience of neonatal medicine and I hope to build on what I learnt and my experiences from Rood & Riddle after I graduate. I really enjoyed seeing equine practice in America and thought that my three week visit was an invaluable and hugely educational experience. Phoebe Parker QMSTA Report 2012

![Lymphatic problems in Noonan syndrome Q[...]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006913457_1-60bd539d3597312e3d11abf0a582d069-300x300.png)