The Health and Retirement Study

The Health and Retirement Study: What is it and what is its potential use to researchers?

Lori Gonzalez, PhD

What is the HRS?

Since its inception, the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) has provided researchers across disciplines with a wealth of data on the lives of America’s older adults. Researchers have used the HRS to study things like spending and saving before and after retirement, physical and mental health, family life and asset transfers, how older adults spend their time, expectations regarding retirement, genotypes that predict Alzheimer’s and cross-national comparisons of retirement (HRS, 2014). This paper describes the HRS, major modifications to the study, reviews articles that critique the study, provides examples of research that uses the study, and explores possible future research projects.

The HRS began a new generation of survey research conducted on the lives of older adults. The survey replaced the Retirement History Study, a study conducted between 1969-

1979. The Retirement History Study was in need of replacement as it no longer captured the retirement experiences of older Americans. The Retirement History Study, for example, underrepresented blacks, Hispanics, and women. By contrast, the HRS is nationally representative and includes an oversampling of blacks and Hispanics.

The survey has had several objectives since its beginning in 1992. The primary objective was to design a survey that could be used across disciplines to understand decisions regarding retirement from every angle—financial, social, health and so on. The survey seeks to uncover the lives of people before retirement and after and how the following factors interact to affect decisions to retire or not: wealth and income, wealth accumulation and depletion, disability, health, family, program enrollment, dissaving, institutionalization, and health declines.

Other nations have patterned retirement studies after the HRS. The data being collected are similar enough to the HRS that cross national comparisons can be made. For example, in Britain, the English Longitudinal Study of Aging is comparable to the HRS. Sweden,

Denmark, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Spain, Italy and

Greece all also have retirement studies that are comparable to the HRS. Israel, Ireland, the

Czech Republic, Poland and parts of Asia are developing similar surveys. These surveys allow researchers to uncover differences and similarities in retirement experiences across cultures.

How Does the Study Work?

The HRS has been conducted every two years since 1992. The most recent release is from 2012. The following describes the study cohorts, sampling procedures, and how individuals enter and leave the survey.

The HRS consists of several cohorts. The first, the Health and Retirement Survey cohort, consists of persons aged 51 through 61 or those born between 1931 and 1941. The HRS cohort was administered the survey every two years between 1992 and 2010. The second cohort,

Assets and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) cohort, is made up of persons aged

70 or older (those born in 1923 or earlier) and was administered in 1993 and every two years after that. The third cohort, the Children of the Depression (CODA), are people born between

1924 and 1930. The fourth cohort, the War Baby cohort are persons born between 1942 and

1947. The fifth cohort, the Early Boomers consists of people born between 1948 and 1953. The final cohort, the Mid Boomers, were born between 1954 and 1959. Figure 1 below summarizes the study years and cohorts.

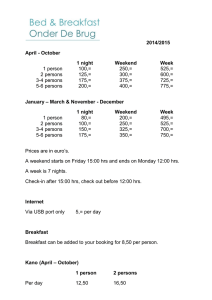

Figure 1: HRS Study Years and Cohorts

Source: “Growing Older in America: The Health & Retirement Study”

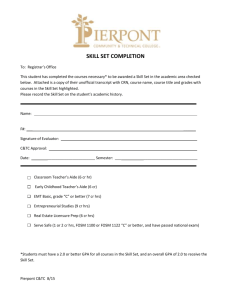

The response rate for the HRS is relatively high. Figure 2 below shows the numbers of respondents and response rates by cohort and year.

Figure 2. HRS Respondents and Response Rate by Cohort and Year

As previously mentioned, there is an oversampling of blacks (1.86:1), Hispanics (1.72:1), as well as Floridians (2:1). The study initially did not interview those who were institutionalized

(ex: those in nursing facilities or jail), but if a respondent eventually became institutionalized, they were included in the study. The HRS sample design was a multi-stage area probability sample design with four distinct selection stages. The AHEAD sample design is the same as the

HRS sample design with one exception—those who were born in 1914 or earlier were selected using a dual frame approach. The War Babies cohort also used the HRS sample design with the difference that some of the respondents were age ineligible spouses of the HRS, or AHEAD age eligible respondents who were already included in the study. The Children of the Depression cohort was drawn from Health Care Financing Administration files (HRS, 2014).

Questions in the survey are asked of the individual (if they are not married) or of the individual and/or their spouse. Each question, if the person is married, is answered only by one of the two. How this is done is not consistent across household or across surveys. The survey is conducted on the telephone unless the person does not have a telephone or can’t use the telephone for the duration of the survey due to health reasons (HRS, 2014).

HRS Major Modifications

Over time there have been several major modifications to the HRS, mostly involving the addition of questions, cohorts, and nursing home residents. Questions relating to cognitive and psychosocial measures have been added throughout the years and in 2006, the survey began collecting DNA samples and biomarker data (lung capacity, grip strength, walking ability and blood pressure). In 1998 the HRS saw a major change in the target population with those who are 50 years or older being surveyed every two years. Prior to 1998 the HRS was limited to

those born between 1931 and 1941 and those who were born in 1923 or before. Also taking place in 1998 was the merging of the HRS and AHEAD samples, the addition of those born between 1942 and 1947, and those who were born between 1924 and 1930. Although the nursing home population was initially excluded from the 1992 survey, they have since been included and by 2000, the sample is representative of the U.S. nursing home population (HRS,

2014).

Future endeavors will include locating HRS respondents in other studies that began earlier in the HRS respondents’ lives to have a better life course understanding of events that led up to retirement. The hope is to be able to have a complete picture of individual’s lives from birth until death (HRS, 2014).

Critiques of the HRS

One set of literature looking at the HRS focuses on evaluating the study itself. Several issues have been examined including population representativeness, sample attrition, sample questions, respondent reporting, and sample weights. This section reviews that body of literature.

The HRS has been critiqued for its representativeness of the larger population. These studies have largely focused on specific topics. One study (Lackman and Spiro, III 2002), for example, looked at the HRS for its representativeness of the population for studies of cognition.

This study found that the AHEAD cohort is suitable enough to make generalizations to the larger population and that comparisons can be made across socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and across other surveys including the Americans’ Changing Lives and

Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. The study also noted some

weaknesses of the HRS including: 1) the inability to compare “completing tasks” data over time as questions asked about different tasks, 2) it’s not clear if the battery can detect dementia, and

3) the telephone battery might have been biased against those who have hearing problems.

Another study (Bricker and Engelhardt, 2007) examined HRS population representativeness in the HRS earnings data. The study compared W-2 data for HRS respondents in 1991 and in 2003 and found that measurement error for men and women are higher than in other studies, but that the error for women is smaller than for men. A study by Meijer and Karoly (2010) compared SSA records to HRS records for low-income representativeness, which is important to health research as some diseases can be more prevalent among the low-income population.

The researchers found that the HRS for all of the years examined, had complete records. They did, however, caution that breaking the low-income sample into small groups (SSI and Medicaid beneficiaries) might produce population estimates that do not reflect the larger population.

With regard to race/ethnicity, one study compared response rates in 2004 to response rates in

2008 and found that minorities were more likely than whites to respond to the survey, except to some supplemental questionnaires like the biomarker survey (Ofstedal and Weir, 2011).

Other critiques have focused on sample attrition in the HRS. The HRS is different than most other surveys in that if a participant drops out of one wave of the survey, they are asked to participate in the next one unless they have requested not to be contacted in the future.

One study (Kapteyn et al., 2006) examined sample attrition for the 1931-1941 cohort for the

2002 study year and found that sample attrition was low. The study did, however, find that when the sample of those who came back to the study (the balanced sample) were excluded, there was significant selection bias for the financial variables. Therefore, the researchers

recommended using the unbalanced sample for analyses, although it can be difficult to include those who skip waves in panel analyses. Michaud and colleagues (2011) came to a similar conclusion in their study of the 1931-1941 cohort. They found that when the balanced sample was used, there was significant bias especially when looking at the wealth variables. Another study (Banks et al., 2010) compared the HRS to the ELSA for the years, 2002, 2004, and 2006 and found that attrition is four times higher in the ELSA study compared to the HRS for the 55-

65 and 70-80 age groups.

Researchers have examined how the HRS survey questions have changed over time and how those questions are being used in academic research. Jackson and colleagues (2011), for example, looked at how the number of questions have increased over time and how researchers have used the questions in their work. They found that since 2002 the number of questions have increased from 413 to 581. When they looked at which questions were being used for research articles between 2006 and 2009, they found that researchers were primarily using questions relating to health, wealth, income and employment despite the wealth of other topics covered in the HRS. In another study that compared the ELSA, SHARE, KLOSA, JSTAR,

CHARLS and LASI on survey content for chronic diseases, researchers found that the HRS did not contain questions about benign tumors, lung disease, asthma, liver disease, stomach or other digestive disease, peptic ulcer disease, kidney disease, Parkinson’s disease, osteoporosis, or hip or femoral fracture—a limitation of the HRS (Hu and Lee 2011). Other studies have looked at the family and relationship variables in the HRS and found that with regards to family, there are a large number of questions. Relationship questions are included, but are not as plentiful as the family questions. The study also collects extensive siblings’ data, however it is seldom used

(Bianchi, 2011). Another study looked at the questions regarding health insurance and

Medicare. Ayanian and colleagues (2011) found that since 2002 there have been improvements in the types of coverage questions. For example, the HRS began collecting data about how individuals choose their insurance company (e.g., advertisements, etc.), long-term care coverage, prescription drug coverage, number of hospitalizations, doctor visits, satisfaction with medical care. They also noted that the time that it takes to link individuals in the HRS to

Medicare claims data has shortened. The study also noted several issues with HRS data including: the insurance section is overly lengthy compared to other sections, Medicare claims data cannot identify contract identifiers or geographic location, and there is no Medicare Part D data. Levy and Gutierrez (2009) in their review of the insurance section also note that it’s comprehensive. They caution, however, that in 1992, respondents were asked about their insurance coverage and their spouse’s and then in 1996 and after, both the respondent and their spouses were asked separately. The implication is that when using the 1994 data, you must also use the 1992 data since they are linked. From 1996 and on, this is not the case.

Another study focused on economic data collected and concluded that although the data are, for the most part, comprehensive, the assets section contains some outliers and the pensions section is missing a significant amount of data (Venti, 2011).

Yet, other critiques have looked at the HRS for respondent bias. One study (Gouskova

2013) looked at the issue of telescoping in reporting inheritance (reporting that one received an inheritance more recently than they’ve actually received one, causing the inheritance to be reported in more than one wave of the study), and found that between 1992 and 2008 five to ten percent of individuals reported that they received an inheritance in more than one wave.

Gouskova developed an algorithm that can reduce duplicate inheritance reporting. Another study looked at respondent bias in medical spending reporting and found that 21 percent of respondents do not provide an exact dollar amount in at least one category of medical spending (Goldman et al., 2011). Similarly, Venti (2011) found that respondents had difficulty in reporting exact dollar amounts for pensions. In a study of arthritis prevalence compared rates in the HRS to the NHIS between 1992 and 2002 and found that rates raise between 1992 and 1995, drop to 1992 levels in 1996, rises between 1998 and 2002 not due to natural rates, but instead due to reporting and measurement error in the HRS (Wilson and Howell 2005).

Finally, the HRS makes available sample weights to account for uneven response across waves, non-participation, and differential probability of selection (Gouskova, 2013). The sample weights intend to ensure that the HRS is representative of the target population in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, age and marital status. When compared to the Current Population

Survey (CPS), Gouskova (2013) found that with regard to race/ethnicity, the HRS matched the

CPS before 2004. However, the 2004, 2006, and 2008 weights underestimate older cohort minorities and overestimate younger cohort minorities. Gouskova concludes that each cohort needs its own race adjustment.

Examples of Research Using the HRS

This section offers examples of the types of studies that have used HRS data. Thousands of studies have used the data. A full list of articles that have used HRS data can be found here: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php?p=biblio Below I summarize three recent studies.

The first (Chen and Feeley, 2013) examined the role of social support (the perceived emotional support from one’s social network) and social strain (the negative interactions with

one’s social network) in well-being and loneliness of adults aged 50 and older. The researchers used the 2008 Leave-Behind Questionnaire of the HRS to test whether social support from one’s spouse, children, family and friends was associated with loneliness and well-being and whether or not higher social strain from these sources is related to loneliness and well-being.

Their models controlled for age, gender, education, marital status, and self-reported health status. Social support was measured by asking participants the following questions about their spouse, children, family members, and friends separately: 1) “How much do they really understand the way you feel about things?”, 2) “How much can you rely on them if you have a serious problem?”, and 3) “How much can you open up to them if you need to talk about your worries?” Social strain was measured by asking participants the following questions: 1) “How often do they make too many demands on you?”, 2) “How much do they criticize you?”, 3)

“How much do they let you down when you are counting on them?”, and 4) How much do they get on your nerves?” They found that with regard to social support, that support from friends and especially from one’s spouse reduced loneliness and that social support from one’s spouse was most important, followed by one’s children, and finally by one’s friends in improving wellbeing. With regards to social strain, Chen and Feeley found that strain coming from one’s spouse had the strongest, negative effect on well-being. In sum, Chen and Feeley (2013) were able to use a subset of HRS data to demonstrate the relationship between social support, social strain, loneliness and well-being among older adults.

The second (de Vries et al., 2014) used data from the HRS, ELSA, and the SHARE

2006/2007 surveys to test the effects of economic inequality on health outcomes across 16 nations. They compared the mean Gini coefficient as a measure of inequality across countries

and the effect that it had on three measures of health—grip strength, lung function, and selfreported physical activity limitation. Controlling for gender, education, income, wealth, individual age and average GDP, de Vries and colleagues found that countries with higher inequality had higher physical activity limitation and lower grip strength, partially supporting the inequality hypothesis. However, they also found that higher inequality was related to lower individual height, which could explain some of their findings. In sum, this study demonstrates how the HRS can be used with other studies to make cross-national comparisons.

The third study examined gender differences in functional limitations for the cohort born between 1931 and 1941 in the HRS for the years, 1992 through 2004. Although previous research had been mixed regarding gender differences in functional limitations and how those manifest over time, Rohlfsen and Kronenfeld (2014) found that males had less functional limitations (measured by items relating to walking, sitting, lifting, climbing, kneeling, pushing, and other abilities) than females in middle and old age and that the gap remains stable over time, suggesting that the gap begins earlier in age. They also found that social structural factors

(e.g., not working or working part time, income and wealth) explained much of the gender differences in functional health and that age was not a significant predictor of limitations.

These results were net of age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, occupation, social support, childhood background factors, behavioral health factors, and health status factors. In sum, the study demonstrates how the HRS can be used to study health outcomes.

Taken together, the above studies show how the HRS can be used to study the social, economic and health aspects of older adults’ lives.

Future HRS Studies

Given its richness, a number of future research endeavors are possible using the HRS. Project topics could include the following:

Family support and transitions to and from the nursing home

Gender differences in retirement timing, savings, etc.

The impact of race/ethnicity on health outcomes and retirement

Predicting nursing home re-entry

International comparisons of nursing home use

International comparison of women’s wealth and retirement

Comparing cohorts in terms of their health behaviors and health over time

International comparison of job tenure and retirement security

Conclusion

In sum, the HRS provides data that is vital to understanding the circumstances surrounding the lives, health and retirement of older Americans. The literature critiquing the HRS shows that while there are some know issues that exist in the data, the HRS is largely representative of the general population.

Given the richness of the data and the ability to make cross-national comparisons with similar studies, the HRS provides a wealth of information for researchers interested in older adults.

REFERENCES

Ayanian, John, Ellen Meara, and J. McWilliams. 2011. “Potential Enhancements to Data on Health

Insurance, Health Services, and Medicare in the Health and Retirement Survey.” Forum for

Health Economics & Policy 14: 1-10.

Banks, James, Alastair Muriel, and James P. Smith. 2010. Attrition and health in ageing studies:

Evidence from ELSA and HRS, RAND.

Bianchi, Suzanne. 2011. “Family Data and Research in the Health and Retirement Study.” Forum for

Health Economics & Policy. 14: 1-15.

Bricker, Jesse and Gary Engelhardt. 2007. “Measurement Error in Earnings Data in the Health and

Retirement Study.” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Chen, Yixin and Thomas Feeley. 2013. “Social Support, Social Strain, Loneliness, and Well-Being among

Older Adults: An Analysis of the Health and Retirement Study.” Journal of Social and Personal

Relationships. 1-21.

De Vries, Robert, David Blane and Gopalakrishnan Netuveli. 2014. “Long-Term Exposure to Income

Inequality: Implications for Physical Functioning at Older Ages.” European Journal of Ageing.

11: 19-29.

Goldman, Dana, Julie Zissimopoulos, and Yang Lu. 2011. “Medical Expenditure Measures in the Health and Retirement Study.” Forum for Health Economics & Policy 14: 1-31.

Gouskova, Elena. 2013. “An Evaluation of HRS Sample Weights.” Institute for Social Research.

Gouskova, Elena. 2013. Inheritance reporting in the Health and Retirement Study data: Evidence of

Forward Telescoping. ISR.

Health and Retirement Study. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu

Accessed 3/2014.

Hu, Peifeng and Jinkook Lee. 2011. “Harmonization of Cross-National Studies of Aging to the Health and

Retirement Study.” RAND.

Jackson, Tina, Mabel Balduf, Laura Yasaitis, and Jonathan Skinner. 2011. “The Health and Retirement

Study-An Evaluation and Scientific Ideas for the Future.” Forum for Health Economics & Policy

14: 1-10.

Kapteyn, Arie, Pierre-Carl Michaud, James Smith, and Arthur van Soest. 2006. “Effects of Attrition and

Non-Response in the Health and Retirement Study.” IZA.

Lachman, Margie and Avron Spiro III. 2002. “Critique of Cognitive Measures in the Health Retirement

Study (HRS) and the Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) Study.”

Levy, Helen and Italo Gutierrez. 2009. “Documentation and Benchmarking of Health Insurance

Measures in the Health and Retirement Study.”

Meijer, Erik and Lynn Karoly. 2013. “Representativeness of the Low-Income Population in the Health and

Retirement Survey.” University of Michigan Retirement Research Center Project #UM11-16.

Michaud, Pierre-Carl, Arie Kapteyn, James Smith, and Arthur van Soest. 2011. “Temporary and

Permanent Unit Non-Response in Follow-Up Interviews of the Health and Retirement Study.”

Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 2: 145-169.

Ofstedal, Mary and David Weir. 2011. “Recruitment and Retention of Minority Participants in the

Health and Retirement Study.” The Gerontologist 51: S8-S20.

Rohlfsen, Leah and Jennie Kronenfeld. 2014. “Gender Differences in Functional Health: Latent Curve

Analysis Assessing Differential Exposure.” Journals of Gerontology 69: 590-602.

Venti, Steven. 2011. “Economic Measurement in the Health and Retirement Study.” Forum for Health

Economics & Policy. 14: 1-18.

Wilson, Sven and Benjamin Howell. 2005. “Do Panel Surveys Make People Sick? US Arthritis Trends in the Health and Retirement Survey.”