The effect of probiotics administration on time to full feeds in neonates

advertisement

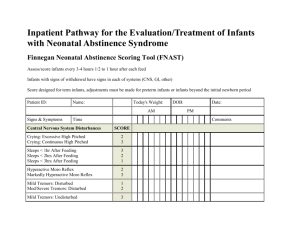

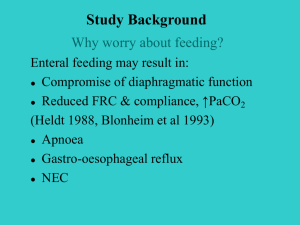

The effect of probiotics administration on time to full feeds in neonates with necrotizing enterocolitis Running Title: Probiotics and NEC John B. Earnest, BS, MS, PhD Jane Dolittel, MD, FAAP, FRCP(Ireland) Mary Sue Mi, MD University of the Health Sciences, Smallville, WI Corresponding Author: John Brown, PhD Neonatal Section 300 N. 7th Street Smallville, WI Email address: john.brown@UHS.edu Introduction Necrotizing enterocolitis is a common problem in neonatology and management of premature infants with NEC has undergone significant change over the past 10 years. The need for surgical intervention has been relatively constant for infants of less than 1500 gm birth weight with 73.7% of such infants requiring intervention in 1999 (1), whereas there has been a significant increase in the use of drains as shown by the Vermont Oxford Network experience for infants of less than 1500 gm birth weight. The NICHD Neonatal Network experience for 2001 was similar with 73% of infants of 1500 gm or less at birth requiring surgery and 20% receiving only medical management(2). There is currently a need to evaluate the role of early intervention as some centers suggest that minimal surgery approaches lessen adverse outcomes including prolonged feeding problems. Even after appropriate treatment and resolution of the acute issues, feeding problems often persist. Groups at high risk for NEC include preterm infants, infants treated for patent ductus arteriousus, SGA infants, and infants who have experienced perinatal hypoxia-ischemia. Anemia is also considered a high risk situation for NEC. Management of feeding issues post-NEC vary among institutions; most often different formulas are tried in an attempt to manage feeding intolerance. When babies have feeding problems for a prolonged period after an episode of NEC, they can develop complications such as TPN-induced cholestasis, bacterial overgrowth, and other problems. Probiotics have been used to try to decrease the risk of NEC in preterm infants. However, there have been concerns that bacteremia with the bacteria in the probiotic preparations could result. Another issue with probiotics is that there are a number of different products available, with little standardization. Also, dosing and timing of administration varies. We wanted to see if administering probiotic agents to neonates after an episode of NEC could improve feeding tolerance by restoring intestinal flora to a more normal pattern, since the normal flora had likely been eradicated during antibiotic therapy given to treat NEC. Methods All infants admitted to the intensive care nursery at University Hospital between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2009 with a diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) were eligible for enrollment in the study. The Institutional Review Board at UH approved the study protocol. After informed consent was obtained from the parents, standard treatment for necrotizing enterocolitis was used until the decision was made by the baby’s attending neonatologist to restart enteral feedings. At that time, babies received 1 ml po/ng daily of “Probiotia”, a readily available probiotic preparation consisting of bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus acidophilus. The probiotic therapy was continued for 2 weeks or until the baby was on full enteral feedings, whichever came first. All study infants were matched with controls consisting of neonates treated for NEC in our unit in the 3 years preceding the study. Controls were matched by gestational age +/- 2 weeks. Data collected in the study infants included gestational age at birth, age at onset of NEC, total time NPO, total number of days to reach full feeding volume, number of times feedings were stopped for more than 4 hours due to feeding intolerance, number of days on parenteral nutrition after feedings were started, and a number of laboratory values including twice weekly total and direct bilirubin and electrolytes, weekly LFTs and chemistries, and weekly weight and head circumference. The same data was collected from medical records of the matched controls. Student’s t-test was used to compare results of study and control infants. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Results A total of 135 infants were eligible for enrollment in the study; of these, 45 were not enrolled secondary to parental refusal, 10 died before study entry, and 15 were started on feedings outside of the study protocol. Thus 65 infants with a diagnosis of NEC were enrolled prospectively. With the matched controls, data were collected from a total of 130 infants. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups except that the mean gestational age of cases was significantly lower than that of controls . Of the cases, 32 (50%) required surgery; 28 (43%) had small bowel resection, and all were treated with antibiotics (typically vancomycin, amikacin, and metronidazole) for 14-21 days. This compared to 24 (37%) of controls with surgery, 22 of whom (91.66%) had bowel resection. Antibiotic therapy was not different between cases and controls (p=0.46). Data on days to full feeding, days receiving parenteral nutrition, and number of episodes of feeding intolerance are shown in Table 2 and show a positive correlation of days on enteral feeds and intake volumes (r=.15, p<.05). While there were no differences observed for electrolytes and weights, there was a trend to lower cholestasis among the cases indicating that the probiotic treatment improved outcomes. DISCUSSION These data indicate that probiotic treatment improved outcomes likely associated with change in intestinal bacterial colonization. In particular, the higher incidence of surgical resection in the control infants with NEC shows that the lactobacillus colonization improves outcomes in NEC patients. We conclude that probiotic treatment results in improved outcomes and is safe. Our data have limitations in that the study was performed over a number of years and involved opinions of different surgeons, however we believe this is not an important factor as the indications for surgery remained similar in the two epochs. Similarly the written procedures for nursing management and parenteral line prevention of CLABSI remained constant throughout the period reducing incidence of parenteral disruptions in the control groups. Finally, stool cultures did not reveal a consistent enteric colonization that was associated with the onset of NEC in the patients. No study infants developed positive blood cultures for lactobacilli and their CRPs remained very low. Hence infections are an unlikely cause of complications. Other complications observed for were diarrhea and grossly bloody stools during the recovery period of which none were found. All babies in both groups lost weight while NPO despite the use of TPN and IV fat. Hence here was no difference in this complication between the groups. Our results are similar to those of O’Levy and colleagues who showed that all operated infants less than 1500 grams birthweight experienced shorter time to full enteral nutrition when probiotics were introduced at the time of restarting feeding(4). They performed a randomized clinical trial in a multi-center network with blind allocation to surgical approaches based upon predetermined and carefully described clinical signs and symptoms including x-ray demonstration of free abdominal air on x-ray. Though our data show the positive effect of probiotic supplements on recovery from NEC and confirm safety of probiotics, we caution that further randomized clinical trials are necessary before confirmation of our findings is possible.