Dog Genome Has Its Day - Home All Things Canid.org

advertisement

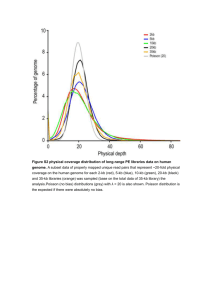

NHGRI Instructive pup. Thanks to Tasha, researchers have a much better handle on the dog genome. Dog Genome Has Its Day By Michael Balter 7 December 2005 Man is about to learn a lot more about his best friend. Scientists report this week the first high-resolution genome sequence of the domestic dog, Canis familiaris. The findings may provide clues to what makes dog breeds look so different and shed light on what separates us from our trusted companions. Judging from the close relationship many people have with their dogs, it might be hard to believe that the evolutionary lineages leading to humans and canines split some 95 million years ago. Despite this distance, some 360 genetic disorders found in humans have also been identified in dogs, and both species suffer from ailments such as cancer, heart disease, and hip dysplasia. Researchers have been keenly interested in the dog genome for what it might tell them about the genetics of disease, as well as the basis for the amazing variety of shapes and sizes represented by the roughly 400 breeds of domestic dog. Now they have an exciting new tool: the genome of a pure bred female boxer named Tasha. Detailed 8 December in Nature, Tasha's sequence has five times higher resolution than a rough draft of a poodle genome reported two years ago by sequencing pioneer J. Craig Venter and colleagues (Science, 26 September 2003, p. 1898). The higher resolution allowed the team, led by genome researchers Eric Lander and Kerstin Lindblad-Toh of the Broad Institute of Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to come to a number of important conclusions. For example, the dog has about 19,000 genes, somewhat less than the 22,000 estimated for humans. At least 70% of these genes have human counterparts, and about 5% are identical to ours. The team also found that certain genes that appear to have undergone accelerated evolution in the human line, including some related to brain function, have also undergone accelerated evolution in the dog. The results "cast serious doubt" on recent high-profile claims that rapid changes in such genes played a role in the evolution of unique features of the human brain (ScienceNOW, 20 April), says evolutionary geneticist John Fondon III of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. The new sequence should be a boon to the study of disease and the genetics behind breed differences, says genome researcher Ewen Kirkness of The Institute for Genome Research in Rockville, Maryland, who worked on both the poodle and boxer sequencing projects. Indeed, the December issue of Genome Research features six papers that use the new sequence information, combined with partial sequencing of other breeds, to investigate a wide range of subjects from canine cancer to the genetics of variation in the size and shape of the dog skeleton. "We can now expect to see a gold rush" of new discoveries, says Fondon.