APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis Synthesis of Findings from the

advertisement

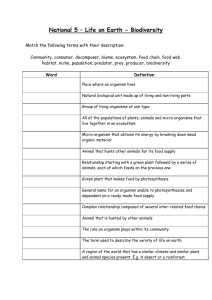

APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis Synthesis of Findings from the Albertine Rift Externship Assessments Conducted under the Education and Training Program in Climate Change and Biodiversity Conservation Funded by the MacArthur Foundation Implemented by The International START Secretariat, Washington, DC and The Institute of Research Assessment, University of Dar es Salaam Synthesis report prepared by the International START Secretariat, Washington, DC Background Little is known about the potential impacts of climate change in the Africa’s Albertine Rift region - an important biodiversity hotspot that is a home to several endangered species of flora and fauna and provides a range of critical ecosystem goods and services. Prior research in this region has largely focused on the individual species level, particularly the conservation of threatened species. In recent years, with substantial evidence pointing towards an already changing climate, there is increasing interest in understanding the potential impacts of changes in temperature and rainfall on ecosystem health, composition and distribution of species, and the sustainability of ecosystem goods and services. Several international conservation organizations such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) have expanded their focus to include implications of climate change for ecosystems and biodiversity in the Albertine Rift. Research in other parts of the world has shown that changes in climate can result in species extinctions, species migrations and range shifts resulting in altered composition of ecosystems (Lovejoy and Hannah, 20051). Ecosystem level changes are driven by the ability of individual species to cope by either adapting to changed climate regimes, shifting their ranges to more favorable locations, or perishing when relocation is not an option due to geographic and biological constraints. The adaptive capacity of species and the resilience of ecosystems is however also driven by a host of non-climatic factors both natural and anthropogenic. It is particularly important to remember that humans are an integral component of natural ecosystems, dependent on a range of ecosystem goods and services for livelihoods, survival and overall well-being (MA, 20052; Figure 1). Their day-to-day natural resource dependent socioeconomic and socio-cultural activities result in a range of direct and direct influences on ecosystem composition and species distribution and survival. These influences are a part of complex feedback loops linking human and natural systems at multiple geographic and temporal scales (Figures 1 and 2). 1 Hannah, L., Lovejoy, T. E., and Schneider, S. H. 2005. In T. Lovejoy and L. Hannah (Eds.), Climate Change and Biodiversity. Yale University, New Haven, pp. 199-210. 2 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC 1 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis Figure 1: Linkages between Ecosystem Services and Human Well-being Source: The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005 Figure 2: Conceptual Framework of Interactions between Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services, Human Well-being and Drivers of Change Source: The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005 2 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis The Albertine Rift externship assessments It is in the context of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment’s framework of the interdependence between biodiversity, ecosystem goods and services and human-well being that the potential influences of multiple drivers of change on human and natural systems were examined by the Albertine rift externship assessments (Table 1). The Externships were conducted under START’s Education and Training Program in Climate Change and Biodiversity Conservation funded by the MacArthur Foundation. The primary objective of the externships was to build the capcity of participants by serving as learning experiences in applying knowledge from the classroom into the field. Five externship assessments were conducted in the Albertine Rift countries of Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania respectively, by participating country teams (Table 1). Each externship was implemented in collaboration with a local host institution, under the guidance of a supervisor. Externships assessed existing natural and anthropogenic stresses in selected Albertine Rift national parks to understand the vulnerability of human and natural systems to changing climatic risks. Physical observations, community surveys, interviews and focus group discussions were coupled with available data and literature to identify the influence of key climatic and nonclimatic drivers on biodiversity and ecosystems goods and services. Assessments were not just restricted to national park boundaries but also accounted for surrounding communities. Table 1: Externship assessments in the Albertine Rift countries Country Externship title Supervisor Burundi DR Congo Rwanda Tanzania Uganda Impact of climate change on water resources and biodiversity conservation in Kibira National Park Impact of climate change on biodiversity and livelihoods in central Virunga National Park Impact of climate change and climate variability on the altitudinal ranging movements of mountain gorillas in Volcanoes National Park Impacts of climate change on biodiversity and community livelihoods in the Katavi Ecosystem Community and park management strategies for addressing climate change in Queen Elizabeth National Park Host Institution Dr. Elias Bizuru# Burundi Nature Action Dr. Arthur Kalonji Tayna Center for Conservation Biology Dr. Elias Bizuru# Department of Biology, National University of Rwanda Dr. Richard Kangalawe Institute of Resource Assessment, University of Dar es Salaam Department of Biology, Mbarara University Dr. Julius Lejju The availability and extent of meteorological data varied for the different field sites with no data available for Virunga National Park in DR Congo due to the destruction of all weather monitoring equipment during a recent period of armed conflict. Communications with community members and park management personnel indicated an increasing variability in climate for all five sites in recent decades, in particular, irregularities and seasonal changes in rainfall, warmer temperatures and increasing frequency of extreme events (Table 2). For example in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda, local communities reported an increased frequency of droughts, unpredictable rainfall seasons, variable rainfall, unusually strong winds and extreme heat regimes. An overall decline in rainfall was noted in Virunga National Park in DR Congo, Kibira National Park in Burundi and the Katavi ecosystem in Tanzania. Rainfall variability and changes in its seasonality were the biggest concern for community respondents due to their impacts on livelihoods. Available local meteorological data from Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania largely 3 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis confirm these observations. Where, future projections of climate are available, they indicate continued increases in temperature and rainfall variability. Community and park personnel expressed greater concern for the day-to-day challenges from non-climatic stresses, which not only impact the management of biodiversity but also to local livelihoods. Anthropogenic activities represent the majority of non-climatic stresses mainly deforestation, agriculture, resource extraction, livestock grazing, competition with wildlife for water resources, overfishing and illegal practices such as hunting and poaching (Table 3). The pressures from a rapidly growing population in the region only serve to compound these stresses. Table 2: Community and park management perceptions of recent changes in climate at the five externship assessment sites Country Climatic drivers Precipitation and Δ * and Δ Δ Δ and Δ Temperature ? Extreme events ? DR Congo Burundi Rwanda Uganda Tanzania Increasing trend Variable trend ? No significant inputs from community members or park management personnel * Deforestation has also contributed to the decline in rainfall in recent decades Habitat loss, habitat modification and habitat degradation are the biggest impacts from livelihood activities i.e. agriculture, livestock grazing, deforestation for timber and fuelwood, and extraction of non-timber forest products such as medicinal plants. Although most communities are largely located on the outskirts of the park, intrusions within the park are not uncommon. Table 3: Non-climatic drivers of change in the Albertine rift region identified by local communities and park management Industrial / Commercial activities Armed conflict Fire DR Congo Burundi Rwanda Uganda Tanzania * * Irrigation farming is a serious threat in Katavi National Park Pests and infectious diseases Invasive species Poaching and hunting Resource extraction Deforestation Non-climatic drivers Agriculture and livestock rearing Country Agriculture and livestock rearing activities significantly increase dependence on water resources. In Tanzania, irrigation farming upstream of the Katuma River causes drying out of the river downstream in the Katavi ecosystem reducing water availability in its wetlands. This impacts wildlife and results in the death of many aquatic animals. Significant buffalo and hippopotamus mortalities were reported during the dry seasons of 2003/2004 and 2005/2006 when the Katuma 4 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis river dried out completely. Livestock also compete with wildlife for fodder and water resources, particularly during periods of scarcity. Overgrazing in areas of limited grass can cause erosion and siltation in water bodies e.g. the Kazinga chanel in Katavi. Grazing within the protected area also enables disease transmission between domestic and wild animals such as typhoid and anthrax. Among other forest resources, bamboo is in high demand in Rwanda for craft making but is also an important food resource of mountain gorillas in Volcanoes National Park. Beekeeping, practiced within the park increases the risk of fire, especially during drought. Fire risk during drought is also enhanced by the practice of burning parkland to enable vegetation regeneration. Fire affected areas can take years to recover. Deforestation for agriculture, timber and fuelwood can contribute to a decline in rainfall due to a loss of forest cover and cause increased erosion and siltation as noted in Kibira National Park, Burundi. Illegal activities such as poaching and hunting present challenges at almost all the study sites and take a great toll on wildlife. Commercial activities such as oil exploration and geothermal development (Uganda), mining and hydroelectric power generation (Burundi), land acquisition for pyrethrum cultivation (Rwanda) have also impacted habitats and can potentially cause the deterioration of air and water quality, introduce of pests and diseases and destroy migratory routes. War and conflict in recent decades have been an important contributor to habitat degradation and habitat loss particularly in DR Congo and Burundi. The influx of armed troops, refugees and a general loss of governance during these periods have resulted in unprecedented deforestation, poaching, resource extraction and an overall negligence of conservation. Several park personnel were also killed. While security concerns persist even today, park authorities are making efforts to re-establish control and enforce regulations. Table 4: Impacts of drivers of change on ecosystems commonly found in the Albertine Rift as depicted in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Albertine Rift Habitat Climate Invasive Over Pollution Ecosystem change change species exploitation type Tropical forest Tropical grassland and savanna Inland water Mountain Driver’s impacts over the last century Low Moderate High Very high Very rapid increase of impact Increasing impact Continuing impact (Adapted from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005) Multiple drivers of change in the Albertine Rift and their impacts are therefore in agreement the findings of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, which has identified impacts of drivers of 5 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis ecosystem change over the past century (Table 4). While the limited scope of the externship assessment could not determine trends over time or the intensity of impact they nonetheless confirm the significant influence of habitat change due to human activities, climate change, invasive species, over-exploitation of resources and pollution in the Albertine Rift. In addition they also emphasize the impact of conflict, which is an added stressor in the region It is important to note that the multiple drivers of change described above, whether climatic and non-climatic, also cross-interact to introduce additional changes in ecosystems. For example adverse climatic conditions such as drought can create favorable conditions for non-climatic drivers such as pests and diseases, invasive species and fire as noted in Uganda. Rampant deforestation during the civil war in Burundi has contributed to a significant decline in rainfall in recent decades. The rapidly growing population in the Albertine Rift is itself an important driver of change due to increasing dependence on the natural resources and the increasing completion with wildlife. Adverse climatic conditions only increase such dependencies. A. Noted impacts of climatic and non-climatic drivers on ecosystems and biodiversity in the Albertine Rift The influence of the drivers of change noted above has already resulted in noticeable impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems (Figure 3). Noted and/or anticipated impacts in the externship sites include: a. Changes in ecosystem composition: In Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda, vegetation displays a trend of changing from grasslands to woodland based on comparison studies of GIS maps from 1954, 1989/90 and 2006 and from local observations of communities and park management. The reduced availability of grass for grazing animals causes out-migration in search of fodder and increases vulnerability to attacks by humans. The increasing prevalence of invasive species has also been noted in Uganda, likely favored by drought and impacts of deforestation and fire. In Kibira National Park, Burundi, the movement of species into new habitat zones and a degradation of the cloud forest is anticipated due to changes in climate. Shifts in species distribution have been noted in Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. b. Changes in species distribution and loss of species: Large mammals such as Elephants, hippopotamus, buffalo, antelopes, gorillas, chimpanzees, Uganda kob, etc. are particularly at risk from changes in habitat and impacts on water resources. The out migration of large mammals away from protected areas in search of food and water resources has been observed in the Virunga, Queen Elizabeth and Katavi, national parks. In Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda, only about 800 mountain gorillas currently remain. With warmer and drier conditions anticipated in future, gorillas may likely change their home ranges to track shifting food resources and/or alter their diet. In Burundi’s Kibira National Park, miniature elephants have already disappeared. The Ericaceae species occupying a niche sub-alpine ecological zone in Kibira, are also likely disappear with changes in climate due to a lack of suitable habitat. c. Changes in plant phenology and animal behavior: In Kibira National Park, Burundi, the early flowering and fruiting of certain plants have already been observed. These changes have increased the aggressiveness of chimpanzees during the months of June-July due to a shortage of fruits and young bamboo, which were earlier abundant at this time. d. Loss of vital ecological functions: Vital ecological functions such as climate regulation, soil and water regulation, fire regulation, disease regulation, maintaining landscape stability, etc. can be affected due to multiple stresses on the system. Loss of forest cover in Burundi has resulted in a noted decline in rainfall in recent decades. Increasing fire frequency due to changes in climate 6 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis and vegetation has been observed in Rwanda. Deforestation in Rwanda and Burundi has also caused erosion and siltation triggering disasters such as landslides. Increasing incidences of malaria in the highlands of Burundi have been experienced in recent years. e. Loss of connective corridors and buffer zones: Demographic pressure resulting in the growing settlements on boundaries of the park results in the occupation of vital migratory corridors and buffer zones in the Albertine Rift protected areas. Figure 3: Interrelationships between drivers of change and their impacts on ecosystem goods and services and human well-being across spatial and temporal scales (Adapted from: The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005) 7 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis B. Impacts of climatic and non-climatic stresses on human wellbeing in the Albertine Rift The impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity directly affect the availability of ecosystem goods and services, influence vital ecological functions and affect human well-being (Figure 3). a. Impacts on livelihoods: Community respondents at all the sites reported a reduction in crop yields due to the increased frequency of droughts, unpredictable rainfall and the increased proliferation of crop pests and diseases. Adverse conditions also reduce the availability of fodder for livestock. In Tanzania, irrigation farming upstream of the Katuma River, which dries it out downstream, further exacerbates impacts of drought. Changes in lake water levels have affected fisheries and salt extraction in Uganda. In Tanzania, the reduced availability of food and water resources within the park causes wildlife to invade neighboring farms, particularly those on the margins and in buffer zones. The migration of wild animals away from the park in search of food and water resources causes a loss of tourism revenue and affects tourism dependent livelihoods in Uganda and Rwanda. In Burundi, low water levels due to drought combined with siltation due to land exploitation reduce the production capacity of the Rwegura dam resulting in power rationing and loss of industrial production. b. Impacts on human health: Lack of access to food, water and critical resources during adverse conditions take a direct toll on human health and greatly increase vulnerability. Important public health concerns attributed to climate changes in the region include increased prevalence of malaria, cholera, infectious diseases, respiratory diseases and malnutrition. Poor water quality during drought poses a threat to human and animal health. Community members are also forced to travel long distances to fetch water during periods of scarcity. Flooding due to intense rainfall also leads to increased incidences of water contamination and outbreaks of diarrheal diseases as noted in Uganda and Burundi. In Burundi, a greater incidence of highland malaria has been observed and cholera is found to be increasingly prevalent in the lowlands particularly during floods. Extreme heat regimes have been experienced in Uganda. Impacts on tourism can have a cascading effect on government wellness programs supported by tourism revenues and targeted at community access to basic services such as health, potable water, education, etc. c. Impacts on human security: Loss of human security results from the loss of livelihoods, lack of access to critical resources, loss of life and property and negative impacts on human health. Armed conflict is a direct threat to human security in DR Congo and Burundi where community members as well as park personnel have been injured and/or killed. Extreme events such as landslides can cause loss of human life and property. Human-wildlife conflicts during the outmigrations of animals into neighboring communities can also result in injuries and mortality. Current status of adaptation The weak understanding of emerging risks from climate change and its interactions with already existing natural and anthropogenic stresses has resulted in the relative absence of any planned adaptation for ecosystems and biodiversity in the Albertine Rift. Park Management initiatives are generally targeted at protecting vegetation and wildlife from degradation by local communities and are usually very symptomatic in nature. For example in Burundi, The National Institute for the Environment and Nature Conservation (INECN) in collaboration with the local administration has banned all illegal activities such as agriculture, poaching, charcoal burning and logging within the park with heavy penalties for violation. The INECN is also making efforts to educate and sensitize local communities about reducing degradation. In Uganda and Rwanda, energy saving cookstoves have been introduced to reduce fuelwood consumption. Reforestation for fuelwood and carbon capture has also been undertaken in Rwanda with limited success due to termite infestation and unsuitability of the new species for firewood. In Rwanda, weather 8 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis monitoring stations and water storage tanks have been installed in collaboration with the International Gorilla conservation Program (IGCP) and the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund. For communities, the high demographic pressures, dependence on subsistence farming, low education levels and large households are important factors that increase their vulnerability to the adverse impacts from climatic and non-climatic stresses. Community coping strategies to address changing risks generally tend to be reactive in nature and are influenced by the greater urgency of meeting livelihood and food security needs. Where resources and / or government support are available, such as in the case of Uganda and Tanzania, communities have adopted strategies like early maturing and disease tolerant crops, irrigation schemes and water harvesting, improved tools and training in advanced farming techniques, improved cattle breeds and better pasture management. Some community members also take up alternate livelihoods such as craft making and small business. Only those lacking access to government services in Tanzania reported a decline in productivity due to climate variability. They depended on more unorganized coping strategies such as timing of crops to rainfall schedules, dependence on groundwater wells and planting trees for firewood. In general a lack of adequate research and data coupled with a lack of awareness of changing climatic risks results in overall weak national response mechanisms. Current conservation strategies, rooted in traditional perceptions of static natural systems, and are not adequately geared towards addressing the dynamic nature of impacts from multiple stressors including climate change. The dependence of communities on ecosystem goods and services and their potential role in the management of protected areas also deserves significant attention. It must be recognized that traditional top-down approaches to conservation by restricting access to protected area resources often result in conflict and could increase the vulnerability of communities dependent on natural resources. A framework for adaptation Given the strong linkages between human and natural systems as demonstrated by the MA (2005) and the urgency of addressing changing climatic risks it is recommended that a framework for action seek to balance the objectives of ecological sustainability with economic efficiency and social equity (Figure 4). Such a framework must be rooted in: a) knowledge generation to increase understanding of individual and combined risks from multiple drivers of change including climate change; b) knowledge communication and networking for building awareness among key stakeholder groups; and c) enabling informed action to address multiple drivers across scales and sectors. It is anticipated that decision making sufficiently informed by the scientific understanding of risks and facilitated by inputs from key stakeholders can result in effective management strategies and establish clear, collaborative, institutional roles to target action for sustaining ecosystem goods and services and livelihoods under a changing climate. Targeted capacity building is clearly critical for supporting these processes of generating and disseminating knowledge and facilitating effective decision making and action in Albertine Rift region where little is known about emerging risks from multiple drivers of change. 9 APPENDIX 4 – Externship Synthesis Figure 4: A framework for adaptation (Adapted from: Elco van Beek, 2009. Managing Water under Current Climate Variability. In, Ludwig, F., Kapat, P., van Schaik, H. and van der Valk, M (Eds.), Climate Change Adaptation in the Water Sector, Earthscan) The externship assessments and courses conducted under START’s Education and Training Program in Biodiversity Conservation and Climate Change have therefore served as a preliminary but important capacity building step in this framework. While the brief duration of the externships and the fact that they were merely ‘assessments’ has limited the depth of information generated it was nonetheless anticipated that they pave the way for greater engagement in regional research and policy initiatives by participants in the future. Indeed, this has been the case as several participants have either taken up climate change and conservation related assignments with the national / regional / international organizations listed above, undertaken PhD research, are engaged with national conservation related governance and policy making, or have received competitive research grants e.g. under START’s African Climate Change Fellowship Program (ACCFP). The career advances made by these participants and their continuing contribution to understanding climatic and non-climatic risks in the Albertine Rift region are a testimony to the success of START’s capacity building initiative. 10