Literature Review on Culture and MNCH

advertisement

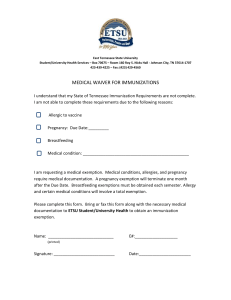

LITERATURE REVIEW: CULTURE AND MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH [MCH LitRev/2] November 2014 Acknowledgements The literature review was compiled for FAMSA by Dr Joy Summerton from Okuhlekodwa Research and Development Consultants, with financial support from the the Reducing Maternal and Child Mortality through Strengthening Primary Health Care in South Africa (RMCH) Programme. The RMCH programme is implemented by GRM Futures Group in partnership with Health Systems Trust, Save the Children South Africa and Social Development Direct, with funding from the UK Government. www.rmchsa.org Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Objectives of the literature review.................................................................................................. 5 3. Approach ......................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Maternal and Child health ............................................................................................................... 5 5. Culture and health ........................................................................................................................... 6 6. Culture in the context of the continuUm of care FOR maternal and child health .......................... 7 6.1 Family planning ......................................................................................................................... 7 6.1.1 6.2 Antenatal Care (ANC) ................................................................................................................ 9 6.2.1 6.3 7. Cultural barriers to uptake of ANC ..................................................................................... 9 Postnatal care (PNC) ................................................................................................................ 11 6.3.1 6.4 Cultural barriers to uptake of family planning services ..................................................... 7 Cultural barriers to uptake of PNC services ..................................................................... 11 Infant and child health ............................................................................................................ 13 Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Acronyms AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care AUC African Union Commission CARMMA Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal and Child Mortality FAMSA Family and Marriage Society of South Africa HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus INP Integrated Nutrition Programme MCH Maternal and Child Health MDG Millennium Development Goals MNCWH Maternal Newborn Child and Women’s Health & Nutrition PNC Postnatal Care RMCH Reducing Maternal and Child Mortality through Strengthening Primary Health Care STI Sexually Transmitted Illnesses TBA Traditional Birth Attendant WHO World Health Organisation 1. INTRODUCTION FAMSA Limpopo, in partnership with CHoiCe Trust, received two grants from the Reducing Maternal and Child Mortality through Stregnthening Primary Health Care (RMCH) Programme to carry out multistakeholder consultantations and further explorations that would contribute to improved uptake of maternal and child health services. The goal was to to improve the health outcomes of women and children in the Waterberg and Capricorn Districts of Limpopo. This literature review carried out under the second grant, responds to the quest to understand the linkages between culture and maternal and child health, with a specific focus on beliefs and practices that have negative consequences for MCH outcomes. It thus aims to enhance insights on culture and its impact on maternal and child health, with a view to inform interventions in the FAMSA MCH and larger RMCH programmes. 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW The overarching objective of the Literature review is to: Carry out desktop research on culture as it impacts on the demand for and uptake of mother and child health services at a community level and with regard to national and local level findings in the province of Limpopo. 3. APPROACH Peer reviewed journal articles published in the mid to late 2000’s pertaining to South Arica and other comparative countries , Department of Health documentation, thesis as well as the proceeding of dialogue workshops carried out in Waterburg and Capricorn districts by FAMSA and Choice Trust in 2013/14 were consulted for this literature review. The focus of this review is on cultural barriers to improving MCH outcomes. The barriers are organised along the continuum of care for mother, infants and children. Other impediments including socio economic and health systems barriers are not covered in this review. 4. MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH Seeing the unlikeliyhood of achieveing the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), specifically Goals 4 and 5, aimed at reducing maternal and child mortality, the African Union Commission (AUC) initiated the Campaign on Accelerated Reduction of Maternal and Child Mortality (CARMMA). CARMMA aims to promote and advocate for renewed and intensified implementation of the Maputo Plan of Action for Reduction of Maternal Mortality in Africa. The targets and indicators for CARMMA in South Africa are in line with MDG 4 (reduced child mortality) and 5 (improved maternal health). CARMMA also builds on and strengthens the Integrated Nutrition Programme (INP) for South Africa and the Roadmap for Nutrition in South Africa. In spite of the innovative and aggressive efforts to reduce infant and child mortality, culture continues to play a significant role in achieving positive health outcomes. Negative cultural beliefs, attitudes and practices are barriers to access for life-saving information and services, including maternal and child health services. 5. CULTURE AND HEALTH Culture is defined as: “An integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communications, languages, practices, beliefs, values, customs, courtesies, rituals, manners of interacting, roles, relationships, and expected behaviors of a racial, ethnic, religious or social group” National Centre for Cultural Competence (2004) 1 Pertaining to health, culture defines systems of health beliefs to explain the causes of illness/illhealth, including how health issues can be cured or treated, and who should be involved in the healing process (what, how and who). As such, the system of health beliefs influences a patient’s perception of health education and health seeking behaviour – both preventive and curative. This means that patients interpret health education based on cultural relevance, which will ultimately determine patient receptiveness to information provided and whether or not they will use the information. This inturn informs health seeking behaviour. A large proportion of South Africans, both rural and urban, hold strong traditional cultural beliefs and practices, which have been found to have a significant influence on their reactions to illness. According to Rukobo2, it is the belief system that determines views of health, illness and disease. In traditional societies the view of the world is one in which all elements of society are linked and functionally integrated. Consequently, medicine, illness, disease and death are understood within the context of culture and religion. In the conception of illness there is a basic distinction between theories of natural and supernatural causation, which forms the cornerstone of traditional cosmological, religious, social and moral worldviews of health and illness34. In the context of biomedicine, when an individual becomes ill, the question of causation pertains to ‘what’ caused the illness and ‘how’ it was caused. The traditional African worldview of causation believes that, in addition, the question of ‘who’ caused it and ‘why’, must also be addressed. This is an essential part of returning the body to its healthy state (healing process). As a result, any form of treatment/therapeutic mechanism given without this understanding may confuse the patient and render the treatment less effective, and even National Centre for Cultural Competence, 2004. Bridging the cultural divide in health care settings. Georgetown: National Centre for Cultural Competence. 2 Rukobo, A.M. 1992. The social context of traditional medicine in Zimbabwe. Institute of Development studies: University of Zimbabwe. Paper presented at the Conference on Ethnomedicine and Health in the SADCC Region in Lesotho, 26-30 October, Maseru Sun Cabanas. 3 Abdool Karim, S.S., Ziqubu-Page, T. & Arendse, R. 1994. Bridging the gap: Potential for a Health Care Partnership between African Traditional Healers and Biomedical Personnel in South Africa. Pretoria: Medical Research Council. 4 Summerton, J.V. 2005. The role of practitioners of traditional medicines treatment, care and support of people living with HIV/AIDS. A thesis submitted at the University of the Free State. 1 unacceptable in some instances5. The medication given by a traditional health practitioner may not alleviate the symptoms of illness, but the reassurance and the psychological effect of the consultation on the patient play a vital role in restoring overall wellness. Similarly, the medication given by the medical practitioner may not provide psychological and spiritual comfort, but may alleviate the physical discomfort of illness. This is indicative of the interdependent and complementary role that biomedicine and traditional healing play in the healing process6. It thus can be deduced that culture plays a significant role in patient compliance to preventive practices and treatment . 6. CULTURE IN THE CONTEXT OF THE CONTINUUM OF CARE FOR MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH 6.1 Family planning The health outcomes of children are determined as early as conception. After a live birth a minimum period of 2 years is recommended before conceiving the next child in order to reduce the risk of adverse maternal, perinatal, neonatal and infant health outcomes7. This recommendation is partly based on the need for the mother to replenish all the necessary nutrients necessary for a healthy pregnancy, as well as to ensure that each child birthed is provided adequate support and care during the most critical years of a child’s life, namely 0-23 months, which includes breastfeeding for a minimum of 2 years. The age of the mother also has a bearing on the health outcomes of children. Teenage pregnancy is associated with increased risks for pre-term delivery, low birth weight and neonatal mortality. One study found that infants born to teenage mothers aged 17 or younger had a higher risk for a low Apgar score8. 6.1.1 Cultural barriers to uptake of family planning services Although individual demographic and socioeconomic factors may shape an individual’s desire and ability to use a service, the cultural environment in which an individual lives exerts a strong influence on the extent to which these factors actually lead to service utilization. Gender role norms, which are deeply rooted in cultural norms, play a significant role in decision-making pertaining to family planning. In many cultures, the number, spacing and timing of children is determined by male partners. Women may need permission from their husband or household elders to seek health care, including family planning9. Therefore, even if women are equipped with knowledge about sexual and Abdool Karim, S.S., Ziqubu-Page, T. & Arendse, R., 1994. Bridging the gap: Potential for a Health Care Partnership between African Traditional Healers and Biomedical Personnel in South Africa. Pretoria: Medical Research Council. 6 Summerton, J.V. 2005. The role of practitioners of traditional medicines treatment, care and support of people living with HIV/AIDS. A thesis submitted at the University of the Free State. 7 World Health Organisation (WHO). 2005. Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing. Geneva: WHO. 8 Chen, X-K., Wen, S.W., Fleming, N., Demissie, K., Rhoads, G.G. and Walker, M. 2007. Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology. (36): 368-373. 9 Stevenson, R. & Hennink, R. 2005. Barriers to Family Planning Service use among the Urban Poor in Pakistan. http://iussp2005.princeton.edu/papers/50657. 5 reproductive health rights and they have access to family planning services, they are unlikely to utilise such services if their sexual partner/husband and household elders do not approve or support them to do so. Teenage pregnancy in South Africa has decreased but still remains unacceptably high with 30% of teenagers (13-19 years) reporting ever having been pregnant10. Over and above economic and systemic/service delivery related impediments to uptake of family planning services, negative cultural beliefs, attitudes and practices are drivers of teenage pregnancy. Talking about sex and sexuality is regarded as taboo in many cultures. The custodians of culture are bestowed with the responsibility to impart information about sexual health. However, such information does not adequately address contraception and protection from HIV and AIDS. One study in the Vhembe District of Limpopo reported that initiation schools play the main role in educating both boys and female adolescents about issues related to sexual health. However, contraceptive use was not covered in the education programme of initiation schools. The study also revealed that culture determines the person who is responsible for talking to adolescents about sex. An aunt is the most prominent person bestowed with the responsibility to talk to adolescents about sexual health issues. However, this strategy is ineffective as the aunt often does not stay in the same household as the adolescents. As a result, the teachings are once-off events. Furthermore, the focus of the information shared is on the meaning of adolescence and preventing pregnancy, with little if any information about how to prevent unwanted pregnancy and HIV and AIDS11. Another study in Limpopo found that poor use of contraception amongst adolescents is compounded by the belief that continued usage will result in infertility – a condition which is perceived as unacceptable in their culture. There is also the ‘magical age’ of 22 years where women are expected to have had a child in order to be perceived as a ‘normal’ girl. There is significant pressure from peers and elders for young girls to prove complete womanhood by having a baby, and failure to do so is frowned upon12. Given the need amongst young people to ‘belong,’ it is seen as a necessary rite of passage for young women in the province. Anecdotal evidence (from KwaZulu-Natal) also points to fear of infertility amongst men, caused by contraceptive use, being a barrier to uptake of family planning services. The aforementioned cultural barriers undermine efforts to reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality in Limpopo. Willan, S. 2013. A Review of Teenage Pregnancy in South Africa – Experiences of Schooling, and Knowledge and Access to Sexual & Reproductive Health Services. Partners in Sexual Health. http://www.hst.org.za/sites/default/files/teenage%20pregnancy%20in%20south%20africa%20final% 2010%20may%202013.pdf 11 Lebese, R.T., Maputle, S.M., Ramathuba, D.U. & Khoza, L.B. 2013. Factors influencing the uptake of contraception services by Vatsonga adolescents in rural communities of Vhembe District in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid 18(1), Art. #654, 6 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.654 12 Lomofsky, D., Mzozoyana, A. & Davids-Mzozoyana, C. 2007. An assessment report on the status of the organisational capacity of the South African Youth Council-Limpopo Chapter (SAYC-LC) on behalf of MultiSectoral Support Programme funded by DFID. Cape Town: Southern Hemisphere and Research LampPost. 10 6.2 Antenatal Care (ANC) Recognising the need to increase the uptake of antenatal care services, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended a minimum of four focused antenatal visits to enhance the quality of care, as opposed to the quantity of care, with a view to reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality. The WHO also advocates for early bookings/uptake of ANC within the first 12 weeks, and no later than 20 weeks. The South African Basic Antenatal Care (BANC) guidelines stipulate five visits, with the first visit occurring in the first 12 weeks. Follow-up visits are then required at 20, 26, 32 and 38 weeks respectively13. Essential interventions in ANC include: i) identification and management of obstetric complications such as preeclampsia; ii) tetanus toxoid immunisation; iii) intermittent preventive treatment for malaria during pregnancy (IPTp); and iv) identification and management of infections including HIV, syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)14. ANC is the prime opportunity to promote and educate mothers about the importance of skilled attendance at birth and adopting healthy behaviours such as good nutrition and nutrient supplementation, breastfeeding, early postnatal care and planning optimal child spacing. 6.2.1 Cultural barriers to uptake of ANC In spite of an estimated 97% of pregnant women in South Africa having had access to ANC during their pregnancies, with 71.4% receiving antenatal services five times during their pregnancy, as well as the majority of these women having access to a trained birth attendant, the majority of women still access ANC services late in pregnancy (third trimester)15. It is estimated that more than 80% of Africans utilise the traditional healing system for preventive and curative services. Traditional health practitioners are often the first health care provider consulted, even when western health care services are accessible (proximity and cost). In the case of ANC, traditional health practitioners are consulted to protect the mother and foetus from supernatural forces that cause illness and to ensure a healthy pregnancy and birth. This usually entails dietary adjustments, performing of rituals and use of traditional medicines. Perception of pregnancy From a western worldview of disease epidemiology, pregnancy is a condition that requires continuous medical observation. On the other hand, many cultures view pregnancy as a natural event that does not necessitate medical intervention. This view influences health seeking behaviour as pregnancy is not associated with ill-health and thus seeking health care is in direct conflict with this health belief system. This view of pregnancy and childbirth as natural physiological processes serves as justification for home births16 17 18. Department of Health. 2005. Basic antenatal care. Pretoria: The National Department of Health. Lincetto, O., Mothebesoane-Anoh, S., Gomez, P. & Munjanja, S. s.a. Opportunities for Africa’s Newborns. Chapter 2: Antenatal care. WHO. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/publications/aonsectionIII_2.pdf 15 Tshabalala, M.F. 2012. Utilization of antenatal care (ANC) and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) services in East Ekurhuleni sub-district, Gauteng Province, South Africa. Thesis submitted at the University of South Africa. 16 Isenalumbe, A.E. 1990. Integration of traditional birth attendants into Primary Health Care. World Health Forum. 11(2): 192-198 17 Mahlmeister, L.R. 1994. Comprehensive maternity nursing. American Journal Of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 170(2): 603-608 18 Research Team of Minzu University of China. 2010. Study on Traditional Beliefs and Practices regarding 13 14 Care during pregnancy A pregnancy is characteristically diagnosed by trained and untrained traditional birth attendants (TBA) during the first trimester. TBAs are both health educators and health providers. Signs and symptoms of pregnancy include enlargement of breasts and changes in eating habits. In many cultures, pregnancy and childbirth are perceived as family events and thus are guided by experienced mentors in the family, reducing the autonomy and decision-making power of the mother, who is regarded as young and inexperienced. In many instances only close relatives, who are usually the elders, are aware of the pregnancy, and the pregnant woman is advised to conceal her pregnancy until it is at an advanced stage to minimise the risk of being harmed by evil forces. A miscarriage and still birth are perceived to be caused by witchcraft. The pregnancy is preserved physically and spiritually with herbs to prevent malformation of the foetus and miscarriage which could be inflicted by jealous persons. It is believed that having contact with other women at a health facility may subject pregnant women to evil spirits which could harm the foetus. TBAs prescribe traditional medicine to protect mother and baby from evil spirits as well as to facilitate the birthing process19 20 21. For example, TBAs in Zimbabwe give women a special drink to open and widen the pelvis for ease of birth and widen the woman’s introitus manually until her hand can be inserted into the vagina. TBAs also give the following medication to pregnant women: herbs to facilitate quick delivery; traditional enema to empty the lower bowel; and herbs to facilitate postnatal bleeding because retained blood will make the mother ill 22 23. In addition to traditional medicine, TBAs across various cultures also prescribe certain practices for mothers during pregnancy, for example adequate rest and activity to ensure the baby is healthy but not too large; massages to the back and abdomen (performed by a TBA); food restrictions such as refraining from eating eggs which are believed to harden the amniotic membranes; and not consuming meat products such as rabbit, goat, pork or crab, which is believed to cause unwanted physical characteristics to an unborn baby24 25 26. Food restrictions are not usually accompanied by prescribed alternative foods to supplement the dietary requirements of pregnant women, thus increasing the risk of malnutrition for both mother and baby due to micronutrient deficiencies. There is also the belief that an infant born with the amniotic sack still intact is symbolic of good health, wealth, success and all other positive prospects for the infant. Older women prefer that such an infant be born at home as opposed to a hospital in order for them to have access to the amniotic sac. The Maternal and Child Health in Yunnan, Guizhou, Qinghai and Tibet. University of China. 19 Nolte, A. 1998. Traditional birth attendants in South Africa: professional midwives’ beliefs and myths. Curationis. 21(3): 59-66. 20 Ngomane, S., Mulaudzi, F.M. 2010. Indigenous beliefs and practices that influence the delayed attendance of antenatal clinics by women in the Bohlabelo district in Limpopo, South Africa. Midwifery, doi:10.1016/j.midw.2010.11.002 21 Ngubeni, N.b. 2002. Cultural practices regarding antenatal care among Zulu women in a selected area I Gauteng. Thesis submitted at the University of South Africa. Pretoria. 22 Sparks, B.T. 1990. A descriptive study of the changing roles and practices of traditional birth attendants in Zimbabwe. Journal of Nurse Midwifery. 35(3): 150-161. 23 Nolte, A. 1998. Traditional birth attendants in South Africa: professional midwives’ beliefs and myths. Curationis. 21(3): 59-66. 24 Nolte, A. 1998. Traditional birth attendants in South Africa: professional midwives’ beliefs and myths. Curationis. 21(3): 59-66. 25 Bobak, I.M. & Jensen, M.D. 1993. Maternity & gynaecologic care. St Louis: Mosby 26 Andrews, M.M. & Boyle, J.S. 1995. Transcultural concepts in nursing care. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott. sac is burnt and the ashes are mixed with petroleum jelly (Vaseline) and the infant is smeared with the paste from head to toe with the belief that the infant is “anointed” into a life of good health, wealth and success. It is believed that if such a child is born in a hospital, the health care providers will take the amniotic sac and sell it to THPs who will use it to make traditional medicines to bring about luck and success for clients, instead of discarding it as part of medical waste. Women who consult THP/TBA for ANC are less likely to attend a health facility for ANC or will do so late in pregnancy when labour is eminent or only when a serious problem is encountered for which the traditional healing system was unable to address. This has adverse implications for the effective management of women with high risk pregnancies. 6.3 Postnatal care (PNC) Most maternal and infant deaths occur during the postnatal (first six weeks after birth) period. An estimated 18 million women in Africa do not give birth at a health facility which poses further challenges for provision of postnatal care services to women and infants. Low coverage of care in the postnatal period negatively influences other maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) programmes along the continuum of care. For example, the lack of support for healthy behaviours at home, such as exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, can have adverse effects for the child in terms of undernutrition. Additionally, newborns and mothers are frequently lost to follow-up during the postnatal period for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV27. 6.3.1 Cultural barriers to uptake of PNC services A key postpartum practice amongst many cultures is household confinement of mothers and infants for a period ranging anything from a month up to 3 months in some cultures. Various reasons are cited for the confinement which include preventing the mother, who is perceived to be ‘unclean’ from polluting other people in the community; and protecting the newborn from impure air that will lead to infections. PNC necessitates routine check-up six days and six weeks post delivery. However, women who adhere to the cultural practice of postpartum household confinement may not be able to attend either routine check-ups. Also, if women subscribe to the traditional health belief model, they will not see the necessity to attend PNC in the absence of illness. The implications are far reaching as the infant will also not be taken to a health care facility for immunizations. Traditional health practitioners, through traditional medicines and rituals, are responsible for protecting the infant from illnesses. Lactating women, as is the case with pregnant women, are also subjected to food restrictions, which often reduce the nutritional intake for pregnant women, thus rendering them vulnerable to malnutrition. Breastfeeding is regarded as a key child survival strategy in resource-poor countries, as exclusive breastfeeding effectively reduces the incidence of diarrhoea, respiratory infections and allergies. However, very few women practice exclusive breastfeeding for six months, and instead introduce solids from as early as a few days after birth. Socio-cultural reasons cited for the introduction of supplementary foods before 6 months are mainly founded on the premise that breastmilk is inadequate both in quantity and quality; negative Warren, C., Daly, P., Toure, L. & Mongi, P. s.a. Postnatal care. In ‘Opportunities for Africa’s newborns’. Chapter 4. Pp 79-90. http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/publications/aonsectionIII_4.pdf 27 perceptions about the content of breastmilk; and symbolisms associated with female breasts. These reasons are discussed below. Attitudes towards the quantity, quality and content of breastmilk In many cultures an infant is perceived to receive insufficient food and is thus hungry if the infant cries more than is considered to be normal. The mother is accused of not producing sufficient milk to satisfy the needs of the baby and the baby is thus given solids which are served in a liquid form. The most common solids given to infants include vegetable-based porridge mixed with breastmilk, formula or water. Once again, it is the elder women in the family (mother, mother-in-law, grandmother) and traditional birth attendants who prescribe the introduction of solids before 6 months. Young mothers, who are perceived as inexperienced and who have reduced decision-making power about maternal health, often abandon exclusive breastfeeding in spite of being knowledgeable about the benefits thereof28 29. Some cultures also associate breastmilk with pollution caused by evil forces (bewitchment). Traditional medicines and rituals are often prescribed to purify the mother and thus her breastmilk30. However, fear of causing the infant to be ill may deter a new mother from breastfeeding at all, perceiving the risks to be too high. Even in the event that a working mother decides to practice exclusive breastfeeding, caregivers of the child who believe that the mother’s breastmilk is polluted, will refrain from feeding the infant the breastmilk due to fear of being polluted by the mother’s milk. Colostrum, which is rich in nutrients and the first form of defence for a newborn due to it being high in antibodies, is often associated with “dirt” and thus expressed and discarded, which robs the infant from receiving the necessary antibodies to fight off infections during the first few days of life, when they are most vulnerable31. Symbolisms associated with female breasts Female breasts have different connotations in different cultures, with industrialised societies more prone to associating female breasts with sexual activity. Based on this view, the primary function of female breasts is related to sexual behaviour and pleasure and thus breastfeeding should be practiced in private, as with sexual behaviour. This view diminishes support for breastfeeding which adversely impact women initiating and sustaining breastfeeding, especially exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life. In many developing civilisations female breasts do not create sexual associations both in men as well as in women. In these societies and cultures, the breast has maintained the primary biological function, which is to feed neonates and babies32. Women freely expose their breasts Research Team of Minzu University of China. 2010. Study on Traditional Beliefs and Practices regarding Maternal and Child Health in Yunnan, Guizhou, Qinghai and Tibet. University of China. 29 Daglas, M. & Antoniou, E. 2012. Cultural views and practices related to breastfeeding. Health Science Journal. 6(2): 353-361. 30 Daglas, M. & Antoniou, E. 2012. Cultural views and practices related to breastfeeding. Health Science Journal. 6(2): 353-361. 31 Zeitlyn, S. & Rowshan, R. 1997. Privileged knowledge and mothers’ ‘perceptions’: The case of breastfeeding and insufficient milk in Bangladesh. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 11(1): 56-68. 32 Dettwyler, K. A. 1995. Beauty and the beast: The cultural context of breastfeeding in the United States. In Stuart-Macadam, P & Dettwyler, K.A. (Eds.). Βιocultural Perspective. New York, Aldine De Gruyter. 28 in public places without reservations. This view of female breasts facilitates the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding. 6.4 Infant and child health Immunisation and growth monitoring is a pivotal component of South Africa’s child survival strategy. The Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) is part of the comprehensive Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses (IMCI) Programme that forms part of the PHC package. Although immunization coverage is high nationally, some childhood illnesses are believed to have a cultural significance and thus are only treatable through traditional medicines and rituals. Hlogwana (siPedi for depressed fontanelle) and Temo (siPedi for the red mark/bruise at the back of the neck of an infant sustained during child birth) are two prevalent childhood conditions treated by THPs. Caregivers usually take a child that exhibits signs of dehydration, such as droopy eyes and loss of appetite, diarrheoa and fever, in conjunction with a depressed fontanelle and red spot at the back of the neck, to a THP. Hlogwana and Temo are believed to be caused by pregnant women not adhering to prescribed dietary recommendations, such as refraining from eating eggs, tripe and cold porridge. It is also believed that these two conditions can be caused by a pregnant women being the first to rise and walk around the residential area before any other person during her pregnancy. The belief is that people may place harmful substances (muthi) in her path that may enter her womb if she walks over them. These two conditions are treated by a THP and typically involve burning of traditional medicines in an enamel bowl. The ash from the burnt traditional medicine is mixed with Vaseline (petroleum jelly) into a paste. A razor blade is used to make incisions around the head and neck, and the paste is placed inside the incisions as blood is produced. Other THPs hold the infant by the feet over the smoke of the burning traditional medicine with the belief that the smoke will “scare” the depressed fontanelle back to its normal state. Thereafter, the entire body of the infant (head to toe) is smeared with the ash and Vaseline mixture. The infant should not be washed for 4-5 days and be smeared every evening, from head to toe, with the remainder of the mixture. The use of the mixture at home during the 4-5 days is also believed to rid the home of evil spirits. The caregiver is also given traditional medicine in a powder form which should be mixed with the infant’s porridge every morning till it is completed. Generally, traditional medicines are used to “immunize” children from childhood illnesses and protect the entire family from misfortune and ill health in the process. Mothers who either believe in the traditional healing system or are not the primary decision-makers about the health and wellbeing of infants, will most likely not take infants for immunisation at a health facility or may delay taking an infant to a health facility in the incidence of dehydration. This has negative consequences for the infant. As is the case with other traditional medicines, infants can be exposed to herbal intoxication or drug interactions if mixed with medicines prescribed at a health facility. In addition, traditional medicines are usually mixed with an infant’s food, which may encourage early introduction of solids. 7. CONCLUSION Culture plays an integral role in how health education messages are received and in decision making with regard to health seeking behaviour. The traditional healing system is rooted in culture, informs preventive and curative practices and tends to focus on the psychological effect of a consultation on a patient and their overall wellbeing This orientation and the mere co existence of two health systems – the traditional healing system and the public health system, have a direct influence on the demand for and utilisation of MCH services at public health care facilities and consequently on MCH outcomes. The traditional and western health care systems both serve the same communities and both have a vested interest in contributing to the optimal wellbeing of both mothers and children. Taking cognisance of the rights of citizens to practice their culture and consult their health practitioner of choice, be it traditional or western, it is pivotal that the two systems of health care explore and find innovative strategies to collectively reduce harmful practices and improve the quality of care for mothers and children. The literature review should enhance insights on culture and MCH which should be used to inform MCH programming and interventions.