- Society for Research into Higher Education

advertisement

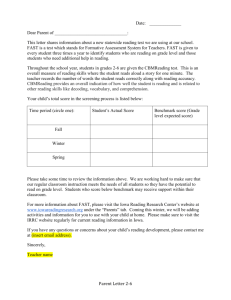

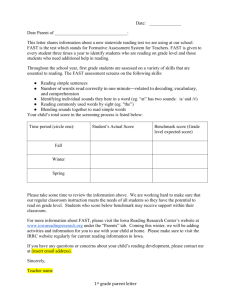

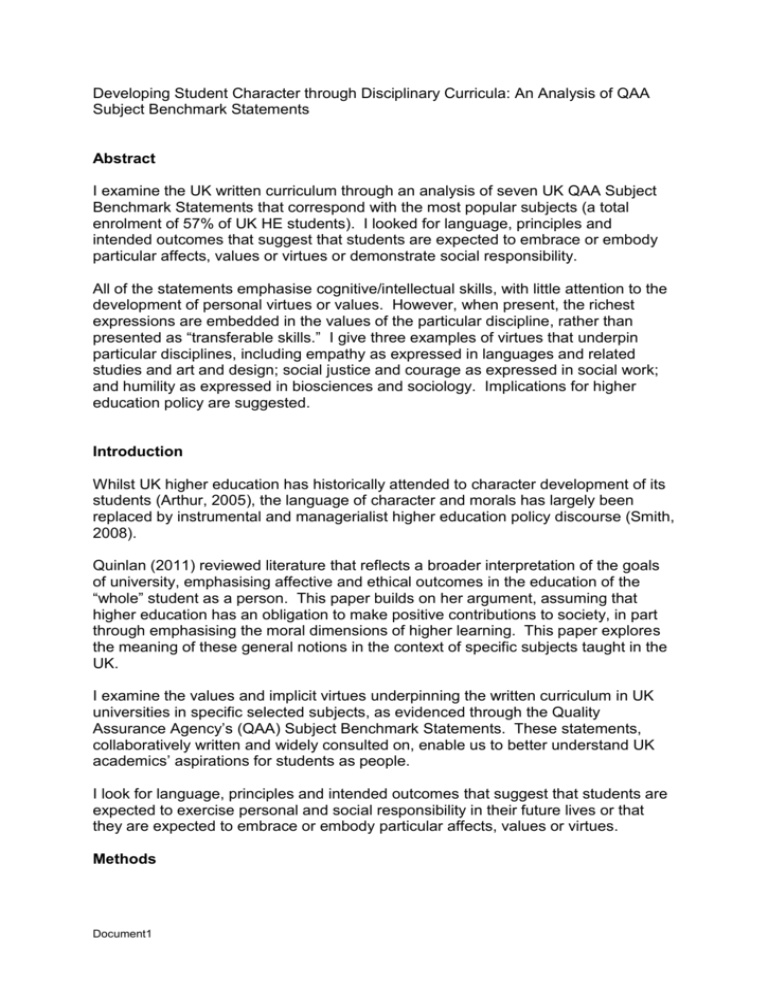

Developing Student Character through Disciplinary Curricula: An Analysis of QAA Subject Benchmark Statements Abstract I examine the UK written curriculum through an analysis of seven UK QAA Subject Benchmark Statements that correspond with the most popular subjects (a total enrolment of 57% of UK HE students). I looked for language, principles and intended outcomes that suggest that students are expected to embrace or embody particular affects, values or virtues or demonstrate social responsibility. All of the statements emphasise cognitive/intellectual skills, with little attention to the development of personal virtues or values. However, when present, the richest expressions are embedded in the values of the particular discipline, rather than presented as “transferable skills.” I give three examples of virtues that underpin particular disciplines, including empathy as expressed in languages and related studies and art and design; social justice and courage as expressed in social work; and humility as expressed in biosciences and sociology. Implications for higher education policy are suggested. Introduction Whilst UK higher education has historically attended to character development of its students (Arthur, 2005), the language of character and morals has largely been replaced by instrumental and managerialist higher education policy discourse (Smith, 2008). Quinlan (2011) reviewed literature that reflects a broader interpretation of the goals of university, emphasising affective and ethical outcomes in the education of the “whole” student as a person. This paper builds on her argument, assuming that higher education has an obligation to make positive contributions to society, in part through emphasising the moral dimensions of higher learning. This paper explores the meaning of these general notions in the context of specific subjects taught in the UK. I examine the values and implicit virtues underpinning the written curriculum in UK universities in specific selected subjects, as evidenced through the Quality Assurance Agency’s (QAA) Subject Benchmark Statements. These statements, collaboratively written and widely consulted on, enable us to better understand UK academics’ aspirations for students as people. I look for language, principles and intended outcomes that suggest that students are expected to exercise personal and social responsibility in their future lives or that they are expected to embrace or embody particular affects, values or virtues. Methods Document1 I did a discourse analysis of the subject benchmark statements corresponding to the five subject areas which account for the largest percentage of UK first degree students in 2010-2011, according to Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA, 2012) data (see Table 1). I also investigated languages (the most popular humanities subject) to ensure that I sampled a range of disciplinary clusters (e.g. arts/humanities, social sciences, sciences) both pure and applied. Table 1. Popular HESA first degree subjects by Selected QAA honours benchmark statements HESA First Degree Subject Business and administrative studies Biological sciences Social studies % of UK HE students study first degrees in this subject in 20102011 13.1% Honours Degree QAA Subject benchmark statement selected 9.9% 9.5% General Business Management (2007) Creative arts and design Subjects allied to medicine Languages 9.5% Bioscience (2007) Social Work (2008), Sociology (2008) Art and Design (2008) 8.8% Health Studies (2008) 6.3% Languages and related studies (2007) Total of sample: 57.1% of first degree undergraduates Findings All of the subject benchmark statements emphasise cognitive/intellectual skills, with little attention to the development of personal virtues or values. However, when present, the richest expressions are embedded in the values of the particular discipline, rather than presented as “transferable skills.” I give three examples of virtues that underpin particular disciplines, while being absent from others. Empathy Empathy emerges most prominently in language studies. The authors (Languages and related studies, 2007) explain: “all students of languages will develop sensitivity to, and awareness of, the similarities and dissimilarities between other cultures and societies, and their own. In particular… they will have an appreciation of internal diversity and transcultural connectedness, and an attitude of curiosity and openness towards other cultures.” (p. 8) Cultural understanding is coupled with “mediating skills and qualities of empathy” (p. 10) and “an ability to articulate to others the contribution that the culture has made at 2 a regional and global level.” Intercultural understanding is a core value embedded in language studies, with graduates serving as empathic ambassadors and mediators. Art and Design students are expected to develop as creative people, using “curiosity, imagination and empathy.” This combination is connected with both culture and creativity, insofar as students need to “visualise the world from different perspectives” and make “a commitment to improving the quality of one’s own and others’ cultural experiences.” Social Justice and Courage Social justice features prominently in the social work benchmark statement, which emphasises the moral dimensions of social work (200practice. For instance, students need to understand, “the complex relationships between justice, care and control in social welfare and the practical and ethical implications of these.” Students should work, “with others to increase social justice by identifying and responding to prejudice, institutional discrimination and structural inequality.” (p. 13) Graduates will need to “challenge others when necessary, in ways that are most likely to produce positive outcomes.” (p.13) Challenging others, particularly authorities and established norms, on the basis of intangible values like dignity, choice, respect, ethics, care and justice demands moral courage. While the benchmark statement doesn’t use words like courage, this virtue seems to be a key, implied requirement. Humility Biosciences (2007) and Sociology (2008) emphasise the incompleteness and provisionality of knowledge, suggesting humility. Both statements articulate the methodologies and epistemologies of knowledge construction in their fields. For instance, “the biosciences exist in an environment of current hypotheses rather than certainty….” (p.1). In both cases, the fields are aware of the ways in which their fields matter to society, referring to debates with significant implications. Perhaps because of the potential uses and misuses of knowledge in their field, they want students to embrace the tentativeness and contested nature of the knowledge itself and appreciate the limitations of the discipline. Discussion The structure of the QAA template seems to constrain the discourse. Each statement contains sections called: Introduction, The nature and scope of the field; subject knowledge, subject-specific and transferable skills; Teaching, Learning and Assessment; and Benchmark Standards. The first two are more revealing of moral commitments than other sections. Written in paragraphs, rather than bullet points, they often convey the “non-negotiables” of the field, defining values, perspectives, methods, questions, concerns and why the field matters. While some disciplines used these discursive sections to make their values explicit, the structure of the benchmark statements does not invite educational leaders and teachers to reflect upon or articulate the virtues or habits of heart students should adopt. Focusing merely on knowledge and skills does not require teachers to consider to what end or for what purposes those knowledge or skills might be applied, or the responsibilities that accompany their use. 3 Policy-makers might consider altering the benchmark statement templates, adding a heading such as “attitudes,” “character strengths” or “graduates’ contribution to society” to highlight these aspects of higher education. References Arthur, J. (2005) ‘Student character in the British University’, in Arthur, J. and Bohlin, K.E. (eds.) Citizenship and higher education: The role of universities in community and society, London and New York: RoutledgeFalmer, pp. 6-24. Higher Education Statistics Agency (2012). Table D - HE students by subject area(#5) and level of study 2010/11. Accessed on 27 February 2013 at: http://www.hesa.ac.uk/ Quality Assurance Agency Subject benchmark statements explaining the core competencies at honours degree level, specifically Biosciences (2007), Sociology (2008), Social Work (2008), General Business and Management (2007), Art and Design (2008), Health Studies (2008), Languages and Related Studies (2007). Accessed 27 February at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/ASSURINGSTANDARDSANDQUALITY/SUBJECTGUIDANCE/Pages/Honours-degree-benchmark-statements.aspx Quinlan, K.M. (2011). Developing the whole student: leading higher education initiatives that integrate mind and heart. Stimulus Paper. London: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education. Accessed on 27 February 2013 at: Smith, K. (2008). “Who do you think you’re talking to? – the discourse of learning and teaching strategies, Higher Education, 56:4, 395-406. 4