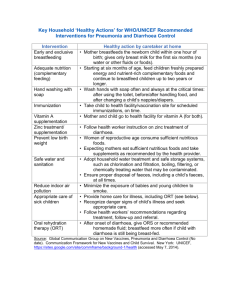

New diagnostics, drugs and vaccines for diarrhoeal disease and

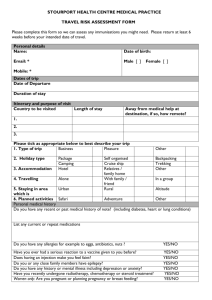

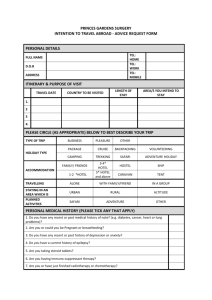

advertisement