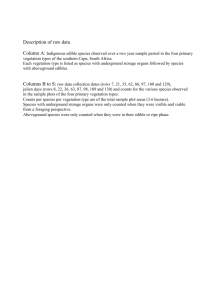

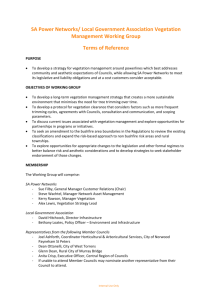

Review of Australia`s Major Vegetation classification and descriptions

advertisement