The Vietnam War

advertisement

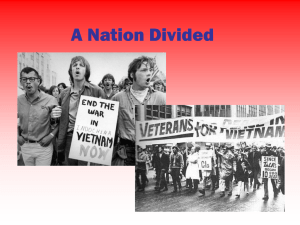

The Vietnam War Vietnam was the longest war in American history and the most unpopular American war of the 20th century. It resulted in nearly 60,000 American deaths and in an estimated 2 million Vietnamese deaths. Even today, many Americans still ask whether the American effort in Vietnam was a sin, a blunder, a necessary war, or whether it was a noble cause, or an idealistic, if failed, effort to protect the South Vietnamese from totalitarian government. Summary: Between 1945 and 1954, the Vietnamese waged an anti-colonial war against France, which received $2.6 billion in financial support from the United States. The French defeat at the Dien Bien Phu was followed by a peace conference in Geneva. As a result of the conference, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam received their independence, and Vietnam was temporarily divided between an anti-Communist South and a Communist North. In 1956, South Vietnam, with American backing, refused to hold unification elections. By 1958, Communist-led guerrillas, known as the Viet Cong, had begun to battle the South Vietnamese government. To support the South's government, the United States sent in 2,000 military advisors--a number that grew to 16,300 in 1963. The military condition deteriorated, and by 1963, South Vietnam had lost the fertile Mekong Delta to the Viet Cong. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson escalated the war, commencing air strikes on North Vietnam and committing ground forces--which numbered 536,000 in 1968. The 1968 Tet Offensive by the North Vietnamese turned many Americans against the war. The next president, Richard Nixon, advocated Vietnamization, withdrawing American troops and giving South Vietnam greater responsibility for fighting the war. In 1970, Nixon attempted to slow the flow of North Vietnamese soldiers and supplies into South Vietnam by sending American forces to destroy Communist supply bases in Cambodia. This act violated Cambodian neutrality and provoked antiwar protests on the nation's college campuses. From 1968 to 1973, efforts were made to end the conflict through diplomacy. In January 1973, an agreement was reached; U.S. forces were withdrawn from Vietnam, and U.S. prisoners of war were released. In April 1975, South Vietnam surrendered to the North, and Vietnam was reunited. The Meaning of the Vietnam War For today's students, the Vietnam War is almost as remote as World War I was for the soldiers who fought it. Now that the United States and Vietnam have normalized relations, it is especially difficult for many young people to understand why the war continues to evoke deeply felt emotions. Thus, it is especially important for students to learn about a war whose consequences strongly influence attitudes and policies even today. 1 The Vietnam War was the longest war in American history and the most unpopular American war of the 20th century. It resulted in nearly 60,000 American deaths and an estimated 2 million Vietnamese deaths. It was the first war to come into American living rooms nightly, and the only conflict that ended in defeat for American arms. The war caused turmoil on the home front, as anti-war protests became a feature of American life. Americans divided into two camps--pro-war hawks and anti-war doves. The questions raised by the Vietnam War have not faded with time. Even today, many Americans still ask: Whether the American effort in Vietnam was a sin, a blunder, or a necessary war; or whether it was a noble cause, or an idealistic, if failed, effort to protect the South Vietnamese from totalitarian government; Whether the military was derelict in its duty when it promised to win the war; or whether arrogant civilians ordered the military into battle with one hand tied and no clear goals; Whether the American experience in Vietnam should stand as a warning against state building projects in violent settings; or whether it taught Americans to perform peacemaking operations and carry out state building correctly; Whether the United States’ involvement in Vietnam meant it was obligated to continue to protect the South Vietnamese. Images of a Tragic War The prize-winning photographs are among the most searing and painful images of the Vietnam War era. These images helped define the meaning of the war. They also illustrate the immense power of photography to reveal war's brutality. One photograph shows a Buddhist monk calmly burning himself to death to protest the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese government. Photographs of this horrific event raised a public outcry against the corruption and religious discrimination of the government of Ngo Dinh Diem, the Catholic president of South Vietnam. Eight more monks and nuns immolated themselves in the following months. Another photograph shows a 9-year-old girl, running naked and screaming in pain after a fiery napalm attack on her village. The napalm (jellied gasoline) has burned through her skin and muscle down to her bone. The photograph of her anguished, contorted face helped to end American involvement in the Vietnam War. A third image shows a stiff-armed South Vietnamese police chief about to shoot a bound Viet Cong prisoner in the head. The victim, a Viet Cong lieutenant, was alleged to have wounded a police officer during North Vietnam's Tet offensive of 1968. The photograph became a symbol of the war's casual brutality. A fourth photograph, taken by a 21-year-old college journalist, shows the body of a 20year-old student protestor at Ohio's Kent State University lying limp on the ground, shot to 2 death by National Guardsmen. In the center of the picture, a young woman kneels over the fallen student, screaming and throwing up her arms in agony. A fifth picture captured the fall of Saigon during the last chaotic days of the Vietnam War. The photo shows desperate Vietnamese crowding on the roof of the U.S. Agency for International Development building trying to board a silver Huey helicopter. Taken on April 30, 1975, the photograph captured the moment when the last U.S. officials abandoned South Vietnam, and South Vietnamese military and political leaders fled their own country, while hundreds of Vietnamese left behind raise their arms helplessly. Photographs have the power to capture an event and burn it into our collective memory. Photographs can trap history in amber, preserving a fleeting moment for future generations to re-experience. Photographs can evoke powerful emotions and shape the way the public understands the world and interprets events. Each of these pictures played a role in turning American public opinion against the Vietnam War. But pictures never tell the full story. By focusing on a single image, they omit the larger context essential for true understanding. Phan Thi Kim Phuc, the 9-year-old girl running naked down the road in the photograph, was born in 1963 in a small village in South Vietnam's Central Highlands. Kim Phuc was the daughter of a rice farmer and a cook. In June 1972, she and her family took refuge in a Buddhist temple when South Vietnamese bombers flew over her village. Four bombs fell toward her. The strike was a case of friendly fire, the result of a mistake by the South Vietnamese air force. There was an orange fireball, and Kim Phuc was hit by napalm. Her clothes were vaporized; her ponytail was sheared off by the napalm. Her arms, shoulders, and back were so badly burned that she needed 17 major operations. She started screaming, "Nong qua! Nong qua!” (too hot!) as she ran down the road. Her scarring is so severe that she will not wear shortsleeve shirts to this day. She still suffers from severe pain from the burns, which left her without sweat or oil glands over half of her body. Two infant cousins died in the attack, but Kim Phuc, her parents, and seven siblings survived. The man who took her photograph, 21-year-old Huynh Cong "Nick" Ut, was also Vietnamese; his brother was killed while covering combat in Vietnam's Mekong Delta for the Associate Press. After the napalm attack, Ut put her into a van and rushed her to a South Vietnamese hospital, where she spent 14 months recovering from her burns. In 1986, Kim Phuc (whose name means "Golden Happiness") persuaded the Vietnamese government to allow her to go to Cuba to study pharmacology. In 1992, while in Cuba, she met and married a fellow Vietnamese student. Later that year, she and her husband defected to Canada while on a flight from Cuba to Moscow. Today, she serves as an unpaid goodwill ambassador for UNESCO and runs a non-profit organization that provides aid to child war victims. Her husband cares for mentally disabled adults. Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan, the South Vietnamese police chief who executed the Viet Cong prisoner in 1968, had a reputation for ruthlessness. While serving as a colonel in 1966, he led tanks and armored vehicles into the South Vietnamese city of Danang to suppress rebel insurgents. Hundreds of civilians as well as Viet Cong were killed. In early 1968, at the height of the Tet offensive, Loan was working around the clock to defend the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon. He had asked a regimental commander to execute the prisoner, but when the commander hesitated, Loan said, "'I must do it.' If you hesitate, if you didn't do your duty, the men won't follow you." 3 The photograph taken at Kent State in Ohio shows a terrified young woman, Mary Ann Vecchio, a 14-year-old runaway from Florida, kneeling over the body of Jeffrey Miller. Miller, a Kent State University student, had been protesting American involvement in Vietnam even before attending college. At the age of 15, he had composed a poem titled "Where Does It End," expressing his horror about "the war without a purpose." Miller was shot and killed during an anti-war protest that followed the announcement that U.S. troops had moved into Cambodia. An ROTC building on the university's campus was burned, and in response, the mayor of Kent called in the National Guard. On May 4, 1970, the guardsmen threw tear gas canisters at the crowd of student protesters. Students threw the canisters back along with rocks, the guardsman later claimed. The 28 guardsmen fired more than 60 shots, killing four students (two of them protesters) and injuring nine (one was left permanently paralyzed). A Justice Department report determined that the shootings were "unnecessary, unwarranted and inexcusable," but an Ohio grand jury found that the Guard had acted in self-defense and indicted students and faculty for triggering the disturbance. Ho Chi Minh Ho Chi Minh was a tiny man, frail in appearance and extremely deferential. He wore simple shorts and sandals. To his followers, he was known simply as “Uncle Ho.” Ho Chi Minh was born in 1890 in a village in central Vietnam. In 1912, he left his homeland and signed aboard a French freighter. For a time, he lived in the United States-- visiting Boston, New York, and San Francisco. Ho was struck by Americans’ impatience. Later, during the Vietnam War, he told his military advisers, “Don’t worry, Americans are an impatient people. When things begin to go wrong, they’ll leave.” After three years of travel, Ho Chi Minh settled in London where he worked at the elegant Carlton Hotel. He lived in squalid quarters and learned that poverty existed even in the wealthiest, most powerful countries. In Paris, he came into contact with the French left. He was still in Paris when World War I ended and the peace conference was held. Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s call for universal self-determination, Ho wrote,”all subject peoples are filled with hope by the prospect that an era of right and justice is opening to them.” Ho wanted to meet Wilson and plead the cause of Vietnamese independence. Wilson ignored his request. Ho then traveled to Moscow, where Lenin had declared war against imperialism. While in the Soviet Union, Ho embraced socialism. By the early 1920s, he was actively organizing Vietnamese exiles into a revolutionary force. In 1941, Ho returned to Vietnam. The time was right, he believed, to free Vietnam from colonial domination. Ho aligned himself with the United States. In 1945, borrowing passages from the Declaration of Independence, Ho declared Vietnamese independence. However, the French, who returned to Vietnam after World War II, had different plans for Vietnam. 4 The French Vietnam War After World War II, neither France nor England wanted to see the end of their colonial empires. England was anxious to control Burma, Malaya, and India. France wanted to rule Indochina. Under Franklin Roosevelt, the United States sought to bring an end to European colonialism. As he put it, condescendingly: “There are 1.1 billion brown people. In many Eastern countries they are ruled by a handful of whites and they resent it. Our goal must be to help them achieve independence. 1.1 billion potential enemies are dangerous.” But under Harry Truman, the United States was concerned about its naval and air bases in Asia. The U.S. decided to permit France into Indochina to re-assert its authority in Southeast Asia. The result: the French Indochina War began. From the beginning, American intelligence officers knew that France would find it difficult to re-assert its authority in Indochina. The French refused to listen to American intelligence. To them, the idea of Asian rebels standing up to a powerful Western nation was preposterous. Although Truman allowed the French to return to Indochina, he was not yet prepared to give the French arms, transportation, and economic assistance. It was not until anticommunism became a major issue that the United States would take an active role supporting the French. The fall of China, the Korean War, and the coming of Joe McCarthy would lead policymakers to see the French War in Vietnam, not as a colonial war, but as a war against international communism. Beginning in 1950, the United States started to underwrite the French war effort. For four years, the United States provided $2 billion; however, this had little effect on the war. The French command, frustrated by a hit-and-run guerrilla war, devised a trap. The idea was to use a French garrison as bait, have the enemy surround it, and mass their forces. Then, the French would strike and crush the enemy and gain a major political and psychological victory. The French built their positions in a valley and left the high ground to their adversaries. An American asked what would happen if the enemy had artillery. A French officer assured him that they had no artillery, and even if they did, they would not know how to use it. Yet, as the journalist David Halberstam noted, “They did have artillery and they did know how to use it.” Into the Quagmire On May 7, 1954, a ragtag army of 50,000 Vietnamese Communists defeated the remnants of an elite French force at a network of bases at Dien Bien Phu in northwestern Vietnam. The French, fighting to restore their Indochinese empire, planned to strike at their adversaries from a network of eight bases (surrounded by barbed wire and minefields) that they had built at Dien Bien Phu. The Viet Minh, Vietnamese Nationalists led by Ho Chi Minh, bombarded these bases with artillery from the surrounding hillsides. Heavy rains made it impossible to bomb the Vietnamese installations or to supply the garrisons. The French, trapped, were reduced to eating rats and pleaded for American air support. Despite support 5 from Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, President Eisenhower was not willing to commit American air support without support from Britain, Congress, and the chiefs of staff. Following the advice of Winston Churchill, Gen. Matthew Ridgway, and Senator Lyndon Johnson, President Eisenhower decided to stay out. Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia had been a French colony since the late 19th century. During World War II, however, Japan occupied French Indochina. After Japan's defeat, France tried to re-establish control, but met opposition from the Viet Minh. Despite American financial supports, amounting to about three-quarters of France’s war costs, 250,000 veteran French troops were unable to crush the Viet Minh. Altogether, France had 100,000 men dead, wounded, or missing trying to re-establish its colonial empire. In 1954, after French forces were defeated at the battle of Dien Bien Phu, a peace conference was held in Geneva Switzerland. At the conference, the French and the Vietnamese agreed to divide Vietnam temporarily into a non-Communist South and a Communist North, pending re-unification following elections scheduled for 1956. Those elections never took place. South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, with U.S. backing, refused to participate in the elections for fear of an overwhelming victory by Ho Chi Minh. The failure of the South to fulfill the terms of the Geneva Accord led the North Vietnamese to distrust diplomacy as a way to achieve a settlement. In 1955, the first U.S. military advisers arrived in Vietnam. President Dwight D. Eisenhower justified this decision on the basis of the domino theory--that the loss of a strategic ally in Southeast Asia would result in the loss of others. "You have a row of dominoes set up," he said, "you knock the first one, and others will fall.” President Eisenhower felt that with U.S. help, South Vietnam could maintain its independence. In 1957, South Vietnamese rebels known as the Viet Cong began attacks on the South Vietnamese government of Ngo Dinh Diem. In 1959, Hanoi approved armed struggle against Ngo Dinh Diem's regime in Saigon. John F. Kennedy and Vietnam John F. Kennedy arrived in the White House with a far slimmer margin of victory than he had hoped, a mere 100,000 votes. It was an election that seemed to strengthen his enemies more than his friends. Kennedy came into office committed to increasing defense spending and upgrading and modernizing America’s military. Dwight Eisenhower was committed to a cheap defense. “More bang for the buck,” was Eisenhower’s slogan. He relied on nuclear deterrence and covert operations. Kennedy was committed to finding an alternative to nuclear weapons. His answer was counterinsurgency. He wanted to use air power and special forces, such as the Green Berets, to fight guerrilla wars. Kennedy’s foreign policy was based on two major premises. The first was a belief in “monolithic communism”--the idea that all communist movements were orchestrated from Moscow. The second was the domino theory--that should a single strategic country turn communist, surrounding countries were sure to follow. 6 We must remember that, in the early 1960s, one third of the world was communist and another third was non-aligned. In Cuba, Kennedy faced a test run for Vietnam. Kennedy completely misread the Cuban people. He was convinced that there was serious anti-Castro sentiment on the island and that an invasion sponsored by the United States would rally the average Cuban to revolt. Kennedy assumed that Cuba was a small island; however, Cuba is 800 miles long (and would stretch from New York to Chicago). During World War II, it had taken three days and 18,000 Marines to capture the tiny Pacific island from the Japanese. Clearly, an invasion of Cuba would require many more than the 1,500 poorly trained Cuban exiles. It was during Kennedy’s presidency that the United States made a fateful new commitment to Vietnam. The administration sent in 18,000 advisors. It authorized the use of napalm (jellied gasoline), defoliants, free fire zones, and jet planes. The government’s efforts, however, weren’t working. By July 1963, Washington faced a major crisis in Vietnam. Buddhist priests had begun to set themselves on fire to protest corruption in the South Vietnamese government. The American response was to help engineer the overthrow the South Vietnamese president. In 1963, South Vietnamese generals overthrew the Diem government and murdered President Diem. President Kennedy sanctioned Diem's overthrow, partly out of fear that Diem might strike a deal to create a neutralist coalition government including Communists, as had occurred in Laos in 1962. Dean Rusk, Kennedy's secretary of state, remarked, "This kind of neutralism...is tantamount to surrender." By the spring of 1964, fewer than 150 American soldiers had died in Vietnam Escalation under Lyndon Johnson President Lyndon Johnson was reluctant to commit the United States to fight in South Vietnam. "I just don't think it's worth fighting for," he told McGeorge Bundy, his national security adviser. The president feared looking like a weakling, and he was convinced that his dream of a Great Society would be destroyed if he backed down on the communist challenge in Asia. Each step in deepening U.S. involvement in Vietnam made it harder to admit failure and reverse direction. President Johnson campaigned in the 1964 election with the promise not to escalate the war. "We are not about to send American boys 9 or 10,000 miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves," he said. But following reports that the North Vietnamese had attacked an American destroyer (which was engaged in a clandestine intelligence mission) off the Vietnamese coast, Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, giving President Lyndon Johnson power to "take all necessary measures." In February 1965, Viet Cong units operating autonomously attacked a South Vietnamese garrison near Pleiku, killing eight Americans. Convinced that the communists were escalating the war, Johnson began the bombing campaign against North Vietnam that would last for 2 ½ years. He also sent the first U.S. ground combat troops to Vietnam. Johnson believed he had five options. One was to blast North Vietnam off the map using bombers. Another was to pack up and go home. A third choice was to stay as we were and 7 gradually lose territory and suffer more casualties. A fourth option was to go on a wartime footing and call up the reserves. The last choice--which Johnson viewed as the middle ground--was to expand the war without going on a wartime footing. Johnson announced that the lessons of history dictated that the United States use its might to resist aggression. “We did not choose to be the guardians at the gate, but there is no one else,” Johnson said. He ordered 210,000 American ground troops to Vietnam. Johnson justified the use of ground forces by stating that it would be brief, just six months. But the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese were able to match our troop build-up and neutralize the American soldiers. In North Vietnam, 200,000 young men came of draft age each year. It was very easy for our enemy to replenish its manpower. By April 1967, we had a force of 470,000 men in Vietnam. We were learning that there was no light at the end of the tunnel. The Johnson administration's strategy--which included search and destroy missions in the South and calibrated bombings in the North--proved ineffective, though highly destructive. Despite the presence of 549,000 American troops, the United States had failed to cut supply lines from the North along the so-called Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran along the border through Laos and Cambodia. By 1967, the U.S. goal was less about saving South Vietnam and more about avoiding a humiliating defeat. Then, everything fell apart for the United States. We suddenly learned the patience, durability, and resilience of our enemy. In the past, our enemy had fought in distant jungles. During the Tet Offensive of early 1968, however, they fought in the cities. The size and strength of the 1968 Tet Offensive undercut the optimistic claims by American commanders that their strategy was succeeding. Communist guerrillas and North Vietnamese army regulars blew up a Saigon radio station and attacked the American Embassy, the presidential palace, police stations, and army barracks. Tet, in which more than 100 cities and villages in the South were overrun, convinced many policymakers that the cost of winning the war, if it could be won at all, was out of proportion to U.S. national interests in Vietnam. At 3 a.m. on January 31, 1968, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched simultaneous attacks on cities, towns, and military bases throughout South Vietnam. The fighting coincided with the Vietnamese lunar New Year, Tet. At one point, a handful of Viet Cong wearing South Vietnamese uniforms actually seized parts of the American Embassy in Saigon. The North Vietnamese expected that the Tet attacks would spark a popular uprising. The Tet offensive had an enormous psychological impact on Americans at home, convincing many Americans that further pursuit of the war was fruitless. A Gallup Poll reported that 50 percent of those surveyed disapproved of President Johnson's handling of the war, while only 35 percent approved. When the offensive ended in late February, after the last communist units were expelled from Vietnam's ancient imperial city of Hue, an estimated 33,249 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong had been killed, along with 3,470 South Vietnamese and Americans. The former Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who had assured Johnson in 1965 that he was "entirely right" on Vietnam, now stated, "I do not think we can do what we wish to do in 8 Vietnam.” Two months after the Tet Offensive, Johnson halted American bombing in most of North Vietnam and called for negotiations. As a result of the Tet Offensive, Lyndon Johnson lost it all. Senator Eugene McCarthy, who picked up more than 40 percent of the vote, challenged Johnson in the Democratic presidential primary. The next primary was in Wisconsin, and polls showed the president getting no more than 30 percent of the vote. Johnson knew he was beaten and withdrew from the race. Johnson was not invited to attend either the 1968 or 1972 Democratic presidential conventions. Why Vietnam? Numerous factors contributed to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam: the Cold War fears of communist domination of Indochina; a mistaken belief that North Vietnam was a pawn of Moscow; overconfidence in the ability of U.S. troops to prevent the communist takeover of an ally; and anxiety that withdrawal from Vietnam would result in domestic political criticism. So, too, did a series of events in 1961, including the disastrous attack on Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, the erection of the Berlin Wall, and the threat made by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to sponsor national liberation movements around the world. The architects of the Vietnam War overestimated the political costs of allowing South Vietnam to fall to communism. Presidents Kennedy and Johnson feared that losing South Vietnam would damage their chances for re-election, weaken support for domestic social programs, and make Democrats vulnerable to the charge of being soft on communism. The North Vietnamese strategy was to drag out the war and make it increasingly costly to the United States. American leaders also grossly underestimated the tenacity of their North Vietnamese and Viet Cong foes. Misunderstanding the commitment of our adversaries, U.S. General William C. Westmoreland said that Asians "don't think about death the way we do." In fact, the Vietnamese Communists and Nationalists were willing to sustain extraordinarily high casualties in order to overthrow the South Vietnamese government. The United States intervened in Vietnam without appreciating the fact that the Vietnamese people had a strong nationalistic spirit rooted in centuries of resisting colonial powers. In a predominantly Buddhist country, the French-speaking Catholic leaders of South Vietnam were generally viewed as representatives of France, the former colonial power. Communists were able to capitalize on nationalistic, anti-Western sentiment. Nixon and Vietnam In the 1968 election, Republican Richard Nixon claimed to have a plan to end the war in Vietnam, but, in fact, it took him five years to disengage the United States from Vietnam. Indeed, Richard Nixon presided over as many years of war in Indochina as did Johnson. About a third of the Americans who died in combat were killed during the Nixon presidency. Insofar as he did have a plan to bring "peace with honor," it mainly entailed reducing American casualties by having South Vietnamese soldiers bear more of the ground fighting-a process he called "Vietnamization"--and defusing anti-war protests by ending the military draft. Nixon provided the South Vietnamese army with new training and improved weapons and tried to frighten the North Vietnamese to the peace table by demonstrating his 9 willingness to bomb urban areas and mine harbors. He also hoped to orchestrate Soviet and Chinese pressure on North Vietnam. The most controversial aspect of his strategy was an effort to cut the Ho Chi Minh supply trail by secretly bombing North Vietnamese sanctuaries in Cambodia and invading that country and Laos. The U.S. and South Vietnamese incursion into Cambodia in April 1970 helped destabilize the country, provoking a bloody civil war and bringing to power the murderous Khmer Rouge, a Communist group that evacuated Cambodia's cities and threw thousands into re-education camps. Following his election, President Nixon began to withdraw American troops from Vietnam in June 1969 and replaced the military draft with a lottery in December of that year. In December 1972, the United States began large-scale bombing of North Vietnam after peace talks reach an impasse. The so-called Christmas bombings led Congressional Democrats to call for an end of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. In late January 1973, the United States, South Vietnam, the Viet Cong, and North Vietnam signed a cease-fire agreement, under which the United States agreed to withdraw from South Vietnam without any comparable commitment from North Vietnam. Historians still do not agree whether President Nixon believed that the accords gave South Vietnam a real chance to survive as an independent nation, or whether he viewed the agreement as a facesaving device that gave the United States a way to withdraw from the war "with honor." The War at Home The United States won every battle it fought against the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong, inflicting terrible casualties on them. Yet, it ultimately lost the war because the public no longer believed that the conflict was worth the costs. The first large-scale demonstration against the war in Vietnam took place in 1965. Small by later standards, 25,000 people marched in Washington. By 1968, strikes, sit-ins, rallies, and occupations of college buildings had become commonplace on elite campuses, such as Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard, and Wisconsin. The Tet Offensive cut public approval of President Johnson's handling of the war from 40 to 26 percent. In March 1968, anti-war Democrat Eugene McCarthy came within 230 votes of defeating Johnson in the New Hampshire primary. Anti-war demonstrations grew bigger. At the Democratic convention in Chicago, police beat anti-war protesters in the streets while the Democrats nominated Hubert Humphrey for president. Ironically, the anti-war protesters probably helped to elect Richard Nixon as president in 1968 over Humphrey and in 1972 over George McGovern. Anti-war demonstrations peaked when 250,000 protesters marched in Washington, D.C., in November 1969. President Nixon's decision to send American troops into Cambodia triggered a new wave of campus protests across the nation. When National Guardsmen at Kent State University shot four students to death in northeastern Ohio, 115 colleges went on strike, and California Governor Ronald Reagan shut down the entire state's university system. The Final Collapse 10 On the morning of April 30, 1975, a column of seven North Vietnamese tanks rolled down Saigon's deserted streets and crashed through the gates of South Vietnam's presidential palace. A soldier leapt from the lead tank and raised a red, blue, and yellow flag. The Vietnam War was over. Tens of thousands of South Vietnamese massed at the dock of Saigon harbor, crowding into fishing boats. In the fall of 1974, President Nguyen Van Thieu of South Vietnam abruptly ordered his commanders to pull out of the central highlands and northern coast. His intention was to consolidate his forces in a more defensible territory. However, the order was given so hastily, with so little preparation or planning, that the retreat turned into an uncontrollable panic. Consequently, North Vietnamese forces were able to advance against little resistance. On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese soldiers captured Saigon, bringing the Vietnam War to an end. The Vietnam War and Popular Culture No American conflict in the 20th century so tore this nation apart, so scarred its social psyche, so embedded itself in its collective memory, and so altered the public view of institutions, government, the military, and the media. More than 750 novels, 250 films, 100 short-story collections, and 1,400 personal narratives have been published about the war in Vietnam. A few figures in popular culture supported American involvement in Vietnam, including novelists John Steinbeck and Jack Kerouac and actor John Wayne, who starred in hawkish The Green Berets, the only major film made during the war itself. Barry Sadler's 1966 pro-war song "Ballad of the Green Berets" sold 8 million copies. During the war, popular culture tended to deal with the war indirectly. Such novels as Joseph Heller's Catch-22 and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five and such films as Bonnie and Clyde, M*A*S*H, and Little Big Manwere ostensibly about other subjects, but clearly reflected the issues raised by the Vietnam War. Movies like Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, or Platoon created a swampy, fiery hell peopled by psychopaths. As one character in Apocalypse Now puts it, "I love the smell of napalm in the morning." Many of these Vietnam War films featured a scene modeled on the My Lai massacre of 1968, when American troops killed at least 347 unarmed civilians in a South Vietnamese hamlet. The emerging images in the media of the "Vietnam vet" were of a troubled and neglected victim--a scraggly and deranged outcast with a rumpled boony hat, a legless victim converted to pacifism, a returning P.O.W. scarred by unspeakable horrors. During the 1980s, a number of influential films focused on Americans who were prisoners of war or missing in action, such as Uncommon Valor, Missing in Action, and Rambo. In the realm of cinematic fantasy, the United States was able to reap revenge for the frustrations and losses it had experienced in Vietnam. Rambo's most famous line was, "Sir, do we get to win this time?" These films provided consolation concerning the morality of American forces in the conflict. In Uncommon Valor, a character tells a band of fellow veterans about to rescue a group of MIAs: "No one can dispute the rightness of what you're doing." 11 The Costs of the War Le Ly Hayslip was born into a peasant family in Central Vietnam in 1949. Her small village was caught in the crossfire of conflict between the French and Moroccan and Viet Minh soldiers, and later between the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong and the armies of South Vietnam and the United States. The daughter of a rice farmer, Le Ly served as a lookout and messenger for the Viet Cong and planted booby traps for the Viet Cong when she was 12-years-old. She was arrested and tortured by the South Vietnamese government police, and then was sentenced to death by the Viet Cong, who accused her of being a government informer. The men assigned to execute her raped her instead. Like hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese, Le Ly was displaced from her village by the war. She fled to Danang and then to Saigon, where she became a maid, a waitress in GI clubs, and an attendant in a hospital, before trying, out of desperation, to support herself through black market dealing and prostitution. At the age of 20, she married an American construction worker and moved to a San Diego suburb, where she later wrote a harrowing account of her life,When Heaven and Earth Changed Places. An estimated 58,132 Americans died in Vietnam. More than 150,000 were wounded, and 21,000 were permanently disabled. More than 3 million Americans, average age 19, served in the Vietnam War. An estimated 100,000 Americans fled the United States to avoid serving in the conflict, and approximately 50,000 American servicemen deserted. The Veterans Administration estimates that 830,000 Vietnam vets suffered symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder; of that number, 480,000 were so deeply affected that they were considered disabled. Several hundred thousand American troops were exposed to defoliants, such as Agent Orange. The estimated cost of the war in Vietnam during the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations was $176 billion. As a whole, 60 percent of all draft-age American men did not serve in the military between 1963 and 1974, and 98 percent did not see combat. The war's greatest costs and suffering were borne by the Vietnamese people, who may have lost 2 million lives during the conflict. Hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese were displaced from rural villages, and their families splintered. Herbicides and bombs ravaged the countryside. Between 1964 and 1969, the United States dropped more than nine times the tonnage of high explosives on Vietnam as it did in the Pacific theater during World War II. After the war, North Vietnam detained 50,000 to 100,000 former supporters of the Saigon regime in re-education camps. Over a million "boat people," consisting largely of Vietnam's persecuted Chinese minority, fled the country to avoid persecution. The Consequences of the War The Vietnam War had far-reaching consequences for the United States. It led Congress to replace the military draft with an all-volunteer force and the country to reduce the voting age to 18. It also inspired Congress to attack the "imperial" presidency through the War Powers Act, restricting a president's ability to send American forces into combat without explicit Congressional approval. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese refugees have helped restore blighted urban neighborhoods. The Vietnam War severely damaged the U.S. economy. Unwilling to raise taxes to pay for the war, President Johnson unleashed a cycle of inflation. 12 The war also weakened U.S. military morale and undermined, for a time, the U.S. commitment to internationalism. The public was convinced that the Pentagon had inflated enemy casualty figures, disguising the fact that the country was engaged in a military stalemate. During the 1970s and 1980s, the United States was wary of getting involved anywhere else in the world out of fear of another Vietnam. Since then, the public's aversion to casualties inspired strict guidelines for the commitment of forces abroad and a heavy reliance on air power to project American military power. The war in Vietnam deeply split the Democratic Party. As late as 1964, over 60 percent of those surveyed identified themselves in opinion polls as Democrats. The party had won seven of the previous nine presidential elections. But the prosecution of the war alienated many blue-collar Democrats, many of whom became political independents or Republicans. To be sure, other issues--such as urban riots, affirmative action, and inflation--also weakened the Democratic Party. Many former party supporters viewed the party as dominated by its anti-war faction, weak in the area of foreign policy, and uncertain about America's proper role in the world. Equally important, the war undermined liberal reform and made many Americans deeply suspicious of government. President Johnson's Great Society programs competed with the war for scarce resources, and constituencies who might have supported liberal social programs turned against the president as a result of the war. The war also made Americans, especially the baby boomer generation, more cynical and less trusting of government and of authority. Today, decades after the war ended, the American people remain deeply divided over the conflict's meaning. A Gallup Poll found that 53 percent of those surveyed believe that the war was "a well-intentioned mistake," while 43 percent believe it was "fundamentally wrong and immoral." Chronology and Key Figures 1941: Ho Chi Minh forms the Viet Minh. 1946: Viet Minh forces attack a French garrison in Hanoi beginning the first Vietnam War. 1950: President Truman's National Security Council decides to provide military aid for the French war in Indochina. 1954: Following the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, an agreement is reached splitting Vietnam at the 17th parallel into a Communist North and a non-Communist South, pending nationwide elections in 1956. 1955: Ngo Dinh Diem proclaims the Republic of South Vietnam and becomes its president. April 1959: President Dwight D. Eisenhower commits the United States to maintaining South Vietnam's independence. July 1959: Two U.S. advisors are the first Americans killed in a guerrilla attack 20 miles north of Saigon. April 1960: North Vietnam begins mandatory military service as its troops infiltrate South Vietnam. By year's end, about 900 U.S. military personnel are in Vietnam. Nov. 1960: Democrat John F. Kennedy defeats Republican Richard M. Nixon for president. Dec. 1960: The National Liberation Front (the Viet Cong) is proclaimed. 13 May 1961: Kennedy sends 100 Special Forces troops, trained for guerrilla warfare, to Vietnam. Dec. 1961: Secretary of State Dean Rusk says South Vietnam is in "clear and present danger" of communist conquest. Feb. 1962: More American advisors and support personnel arrive. Kennedy warns that American advisors will return fire if attacked. May 1962: In response to communists moving into Laos, U.S. sends 5,000 Marines and 50 fighter jets to Thailand. Oct. 1962: U.S. discovers Soviet missile sites under construction in Cuba. Soviets agree to remove missiles, but crisis heightens fears of superpower conflict. Jan. 1963: In battle of Ap Bac, South Vietnamese and Americans suffer worst defeat to date: five U.S. helicopters downed and three Americans killed. Aug. 1963: Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his "I Have a Dream" speech during civil rights march in Washington. Nov. 1963: South Vietnamese generals kill President Ngo Dinh Diem in a plot condoned by key American officials who felt Saigon could not win under his leadership. Three weeks later, Kennedy is assassinated. Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson succeeds him. 1964: North Vietnam begins infiltrating its regular army units into the South. Aug. 1964: The Maddox, a U.S. destroyer, is slightly damaged by enemy boats in Tonkin Gulf. After a reported second attack--which many later concluded did not occur--Congress passes Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving Johnson authority to intensify the war. Oct. 1964: China explodes its first atomic bomb. Nov. 1964: Johnson elected in landslide over Republican Barry Goldwater, who had pushed for an even tougher approach to Vietnam. Dec. 1964: Bob Hope begins frequent visits to entertain the troops. Jan. 1965: Johnson sends Congress a budget containing the biggest expansion of domestic welfare programs since the New Deal, reflecting his goal of providing funds for both the war and what was called the Great Society. Feb. 1965: Viet Cong attack an American airfield at Pleiku. U.S. bombers attacked targets in North for the first time, in a reprisal for attacks on U.S. bases. March 1965: First U.S. combat troops in South Vietnam land in Da Nang. April 1965: As Johnson formally authorizes combat troops to be used for offensive operations, antiwar movements become more active. Aug. 1965: Large scale race rioting, resulting from the arrest of a black motorist by a white officer, leaves 34 dead in Watts section of Los Angeles. Oct. 1965: Antiwar sentiment continues to build; protests held in 40 U.S. cities. Dec. 1965: American troop strength reaches 184,300; to date there are 636 U.S. deaths. Jan. 1966: Congress is asked for $ 12.8 billion to help finance the war; merits of war debated in Congress, but the money eventually is approved. June 1966: Johnson expands bombing to oil installations in Hanoi and Haiphong. Summer 1966: Race riots break out in Chicago and several other northern cities. Riots escalate a year later. Sept. 1966: U.S. announces that it is using chemicals to destroy enemy's jungle cover, thus introducing the herbicide Agent Orange into the conflict; thousands of American soldiers later say they developed cancer and other afflictions as a result of exposure. April 1967: Boxing champion Muhammad Ali refuses induction into the armed forces, citing religious reasons. He tells reporters, "I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong." 14 Oct. 1967: At least 50,000 protesters march on Pentagon. For first time, opinion polls find more Americans are against the war than support it. Nov. 1967: Democrat Eugene McCarthy announces that he will run as a presidential candidate dedicated to ending the war. Dec. 1967: U.S. military personnel in Vietnam reach 485,600; 16,021 killed to date. Jan. 1968: North Vietnam launches massive Tet offensive, reaching all the way to U.S. Embassy in Saigon; despite heavy communist casualties, public relations victory goes to Hanoi, fueling antiwar movement. Feb. 1968: Viet Cong and North Vietnamese kill 2,800 civilians in Hue. U.S. casualty rate reaches weekly high: 543 killed. March 1968: Johnson announces he will not seek reelection. My Lai massacre of South Vietnamese civilians by American troops leaves hundreds of unarmed civilians dead. April 1968: Rev. King, who had called for total withdrawal from Vietnam, is assassinated. May 1968: Moves toward peace bring first substantive meeting between U.S. and North Vietnam in Paris. Bloodiest month of the war for U.S. casualties, 2,371 Americans killed. June 1968: Robert F. Kennedy, a Democratic presidential candidate opposed to the escalation of the war in Vietnam, is assassinated. Aug. 1968: Violence erupts between police and antiwar demonstrators at Democratic convention in Chicago. Nov. 1968: Richard Nixon, who vowed to achieve peace with honor in Vietnam, defeats Democrat Hubert H. Humphrey in presidential election. May 1969: U.S. proposes peace plan calling for troop withdrawal by both sides. June 1969: Nixon announces that U.S. troops will begin unilateral withdrawal. July 1969: Apollo 11 astronauts land on the moon. Aug. 1969: Woodstock festival, a social and musical milestone, draws an estimated 500,000 to upstate New York. Sep. 1969: North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh dies in Hanoi; successor pledges to continue war. Nov. 1969: Details of the My Lai massacre become public. Dec. 1969: First Vietnam War draft lottery, tying mandatory military service to date of birth, is held in U.S. Feb. 1970: National Security Advisor Henry A. Kissinger begins secret peace talks in Paris; Nixon later appoints him secretary of State. Mar. 1970: The United States begins bombing North Vietnamese sanctuaries and supply routes in Cambodia. April 1970: U.S. and South Vietnamese troops invade Cambodia in effort to cripple enemy supply lines; it is last big operation of the war for the United States. May 1970: Four students killed by National Guardsmen during antiwar protest at Kent State University in Ohio. Dec. 1970: Congress prohibits using troops or advisors in Cambodia and Laos. March 1971: Lt. William L. Calley Jr. convicted of premeditated murder in My Lai massacre. June 1971: New York Times begins publishing top-secret Pentagon Papers, which explored the U.S. decision-making process regarding South Vietnam. July 1971: The 26th Amendment lowers the voting age to 18. Nov. 1971: Nixon announces that U.S. ground forces have taken a defensive role, leaving offensive attacks to the South Vietnamese. Dec. 1971: U.S. military strength declines to 156,800. U.S. death toll, 45,626. March 1972: North Vietnam begins a full-scale invasion of the South. 15 April 1972: In effort to pressure Hanoi on lagging peace talks, bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong resumes after four-year lull. June 1972: Five men seized while breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate building in Washington. July 1972: Actress Jane Fonda, an anti-war activist, goes to Hanoi on a fact-finding mission, poses for pictures with North Vietnamese soldiers, becomes target of criticism in U.S. Oct. 1972: National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger announces, "Peace is at hand." His announcement of a tentative accord turns out to be premature. Nov. 1972: Nixon wins second term, defeating Democrat George S. McGovern. Dec. 1972: The North Vietnamese walk out of the Paris peace talks; American bombers strike at Hanoi and Haiphong. Jan. 1973: U.S., South Vietnam, Viet Cong and North Vietnam sign a cease-fire agreement. March 1973: Last U.S. ground troops leave Vietnam. Nov. 1973: Congress overrides presidential veto of War Powers Act, which limits president's ability to wage war without congressional approval. Jan. 1974: North Vietnam orders major offensive to "liberate" South Vietnam. April 1974: Cambodia falls to Communist Khmer Rouge rebels, who begin program of genocide that kills more than a million Cambodians. Aug. 1974: Nixon resigns in Watergate scandal and is succeeded by Vice President Gerald R. Ford. Sep. 1974: Ford offers clemency to Vietnam draft evaders and military deserters. Apr. 29, 1975: Last U.S. military personnel killed, in rocket attack. Apr. 30, 1975: North Vietnamese capture Saigon, ending the Vietnam War. July 1975: North Vietnam annexes South Vietnam and disbands the National Liberation Front. Dec. 1978: Vietnam invades Cambodia and occupies the country for a decade. Nov. 1982: The Vietnam Memorial in Washington is dedicated. Feb. 1994: The United States ends its 19-year trade embargo against Vietnam. July 1995: The United States extends full diplomatic recognition to Vietnam. NORTH VIETNAM KEY FIGURES Vo Nguyen Giap: Architect of North Vietnam's military victory Ho Chi Minh: Revered in North as father of the country Ngo Dinh Diem: South Vietnamese President assassinated by his generals Nguyen Cao Ky: Air force officer helped lead South in post-Diem era Nguyen Van Thieu: Resigned South Vietnamese presidency shortly before war's end Lyndon Johnson: Inherited presidency and unpopular war Richard Nixon: Took office after nation had turned against war William C. Westmoreland: Controversial U.S. commander William Calley: Platoon leader found guilty in My Lai massacre. He was sentenced first to life, then to ten years in prison. He was freed by order of a civil court in 1974. Robert McNamara: As defense chief, guided U.S. policy Henry C. Lodge: Pushed air war in role as envoy and presidential advisor 16

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)