Diane Redmond, M.Ed. Teacher of the Visually Impaired, Boston

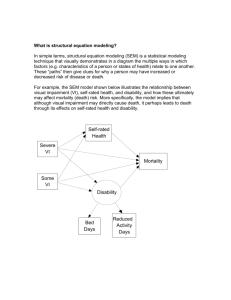

advertisement