equality 2.0 * complementary and alternative paths to

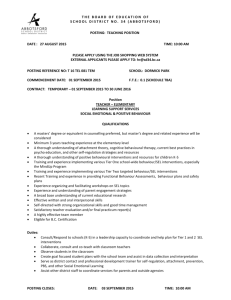

advertisement