Conservation tillage, also called crop residue management, is a

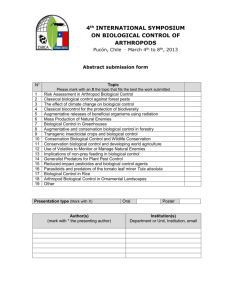

advertisement

SMA 521: Mitigation Strategy Policy December 7, 2011 Conservation Tillage Description Conservation tillage, also called crop residue management, is a method of soil cultivation that leaves a minimum of 30% of the soil surface covered by the previous year’s crop residue. Conservation tillage policy is being implemented at global, national and local levels. In most instances the motivation for promoting conservation tillage is predominantly from the angle of reduced erosion, improved water retention, and improved soil quality; but many policies also promote conservation tillage as a climate mitigation strategy whereby conservation tillage acts as a carbon sink. Some of these policies acknowledge that the actual potential of carbon sequestration through conservation tillage is still under debate in the scientific community, in other instances this scientific uncertainty is not acknowledge. International At the global level, conservation tillage is promoted by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and is highlighted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as a mitigation strategy to reduce energy use and increase soil carbon sequestration. In the IPCC Third Assessment Report, it was estimated that conservation tillage and other agricultural mitigation strategies could reduce CO2 by 350-750 metric tons of carbon per year at a cost of between zero and US$100 per ton of carbon equivalent (Smith et. al. 2007). The IPCC acknowledges that there is a wide range of potential financial costs and sequestration benefits associated with this estimates due to uncertainty in CH4, N2O, and soil-related CO2 emissions (Smith et. al. 2007). As such, the global estimate was not detailed into national or regional estimates (Smith et. al. 2007). The IPCC acknowledges, in addition to uncertainty about the carbon sequestration potential, the need to further quantify other potential greenhouse gas emissions of conservation tillage due to the expanded use of fertilizers and herbicides (Smith et. al. 2007). This particular concern has led some to reevaluate the stated benefits of conservation tillage, particularly the practice of no-till, which tends to result in high levels of herbicide use for weed control (Harbinson 2001). Both Monsanto, the developer of RoundUp, and Syngenta, the developer of Paraquat, are promoting their non-selective broad-spectrum herbicide products as climate change mitigation approaches when applied to no-till cultivation (Monsanto 2011; Paraquat 2011). As of 2008, over 155 million acres of cropland were treated with Roundup and over the past ten years, “no-till or reduced-tillage practices have increased dramatically and are closely associated with adoption of Roundup Ready crops” (Wilson 2011, p. 1). Although the expansion of no-till and other conservation tillage systems is broadly believed to be environmentally beneficial, there are concerns that there could be negative impacts from broad-based herbicide application and concerns that the adoption of conservation tillage under the United Nations process could lead to a future scenario where conservation tillage is prescribed as a global fix with the backing of corporate interests, without recognition that the benefits of conservation tillage are site specific (Harbinson 2001). Federal: US SMA 521: Mitigation Strategy Policy December 7, 2011 Conservation Tillage At the national level, the Natural Resources Conservation Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) encourages conservation tillage through the 2008 Farm Bill’s Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). CSP encourages producers to expand, improve, maintain, and manage existing conservation activities in a voluntary manner (USDA 2010). The program encourages conservation activities through payments of $40,000 per year or $200,000 over a five-year period for instituting new conservation practices and an additional supplemental payment for enacting resource-conserving crop rotation strategies (USDA 2010). Also instituted through the 2008 Farm Bill, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) is another voluntary program that provides financial assistance to producers that plan and implement conservation practices for a contact period up to ten years and up to $300,000 for any six-year contract period (USDA 2009). Conservation tillage is included as a practice that contributes to greenhouse gas reduction in EQIP (Horowitz and Gottlieb 2010). In 2008 USDA through EQIP paid $42.5 million for conservation tillage contracts on 2.7 million acres and sequestering an estimated 1.6 million tons of CO2 (Horowitz and Gottlieb 2010). The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also encourages the practice of conservation tillage on their website, stating that it “Increases carbon storage through enhanced soil sequestration, may reduce energy-related CO2 emissions from farm equipment, and could affect N2O positively or negatively” (EPA 2010, p. 1). The Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) encourages conservation under the Carbon Financial Instrument (CFI) for the agricultural sector. Under the CFI, producers that agree to maintain cropland in continuous conservation tillage (five year period) on enrolled acres are eligible to sell credits for the sequestered CO2 (CCX 2011). Projects must be enrolled through the Offset Aggregator and require independent verification (CCX 2011). The offset issuance rates are based upon estimated carbon sequestration rates for different geographic regions based on soil type (CCX 2009). The United States is divided into Zones A through G and offsets range from a maximum of 0.6 metric tons per acre per year for Zone A to the minimum of 0.2 metric tons per acre per year from Zones D and F (CCX 2009). The differentiation of zones begins to address concerns that carbon sequestration is not equal across all soil types, but it is still difficult to quantify whether the zones accurately account for carbon sequestered through conservation tillage (Mur 2008; Schahczenski and Hill 2009). Given differences in soil type, temperature and other variables it is unlikely that the amount of carbon stores matches the offset emission estimate (Schahczenski and Hill 2009). The CCX verification process verifies that continuous conservation tillage is maintained during the contract period, but does not verify that actual amount of carbon stored (Schahczenski and Hill 2009). In addition, although creating a market for carbon sequestration through land use, CCX does not differentiate between agricultural land converted to conservation tillage and land where conservation tillage was already under implementation, thus it may not contribute to a net decrease in emissions (Muir 2008). Washington At the state level in Washington, there are no regulations governing the implementation of conservation tillage. The Washington State University Extension has conducted research on the transition to conservation tillage and the costs and benefits to producers of making and SMA 521: Mitigation Strategy Policy December 7, 2011 Conservation Tillage maintaining this change in a farming system. The Extension resources assist producers in determining whether and how to convert their croplands to conservation tillage. Washington State University’s Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources (CSANR) conducted an economic analysis of conservation tillage and how carbon credits could be used to encourage a move from conventional to conservation tillage. The report concluded that carbon credits would be effective in encouraging adaptation of conservation tillage in areas where there is a high capacity for sequestration, but would not be a cost effective incentive in areas where there is low capacity for sequestration (Painter 2010). The funds from carbon credits could offset some of the risks and equipment expense associated with a change in land management practices (Painter 2010). Regionally, Washington State collaborates with Oregon and California on information exchange and best practices. Washington is also part of the Pacific Northwest Solutions to Environment and Economic Problems (STEEP) project funded through a USDA grant supported the conversion of farmland to conservation tillage to reduce soil erosion (Kok 2007). Conclusion In regard to conservation tillage’s promotion as a climate mitigation land use management strategy, the national-level appears to be the strongest advocate. The USDA promotes conservation tillage through subsidizing the conversion of farms to conservation tillage as well as funding research at the regional and state level through Extensions and research grants. Given the prominence of the USDA as a federal agency and the nation’s interest in preserving active farmland in the United States it is not surprising that they are the leader in promoting conservation tillage. Literature cited: Chicago Climate Exchange. 2010. Continuous Conservation Tillage and Conversion to Grassland Soil Carbon Sequestration Offsets. http://prod2.chicagoclimatex.com/content.jsf?id=781 Chicago Climate Exchange. 2009. CCX Offset Project Protocol: Agricultural Best Management Practices – Continuous Conservation Tillage and Conversion to Grassland Soil Carbon Sequestration. EPA. 2010. Agricultural practices that sequester carbon and/or reduce emissions of other greenhouse gases. http://www.epa.gov/sequestration/ag.html Harbinson R. 2001. Conservation tillage and climate change. Biotechnology and Development Monitor, No. 46, p. 12-17. http://www.biotech-monitor.nl/4605.htm Horowitz J. and Gottlieb J. 2010. The Role of Agriculture in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Economic Brief No. (EB-15) 8 pp. http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/eb15/ SMA 521: Mitigation Strategy Policy December 7, 2011 Conservation Tillage Kok H. 2007. EB235Ea: STEEP Impact Assessment. University of Idaho, Oregon State University, Washington State University, USDA Agricultural Research Service. Monsanto. 2011. Weed management: Roundup ready system. http://www.monsanto.com/weedmanagement/Pages/roundup-ready-system.aspx Muir P. 2008. Conservation tillage systems. Oregon State University. http://people.oregonstate.edu/~muirp/constill.htm Paraquat. 2007. Conservation tillage earns carbon credits. http://paraquat.com/news-andfeatures/archives/conservation-tillage-earns-carbon-credits Painter K. 2010. An Economic analysis of the potential for carbon credits to improve profitability of conservation tillage systems across Washington State. CSANR Research Report 2010 – 001. Schahczenski J. and Hill H. 2009. Agriculture, climate change and carbon sequestration. ATTRA—National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service. http://www.slideshare.net/ElisaMendelsohn/agriculture-climate-change-and-carbonsequestration-ip338 Smith P., Martino D., Cai Z., Gwary D., Janzen H., Kumar P., McCarl B., Ogle S., O’Mara F., Rice C., Scholes B., Sirotenko O.. 2007. Agriculture. In Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [B. Metz, O.R. Davidson, P.R. Bosch, R. Dave, L.A. Meyer (eds)], Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. USDA. 2010. Farm Bill 2008: Fact sheet: Conservation Stewardship Program. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/national/programs/financial/csp USDA. 2009. Farm Bill 2008: Fact sheet: Environmental Quality Incentives Program. http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/?ss=16&navid=100120310000000&pnavid=1 00120000000000&position=SUBNAVIGATION&ttype=main&navtype=SUBNAVIGATION&pname =Environmental%20Quality%20Incentives%20Program Wilson R. 2011. Roundup Ready crops: How have they changed things? High Plains Journal. http://www.hpj.com/archives/2009/mar09/mar9/RoundupReadycrops-Howhaveth.cfm