File

advertisement

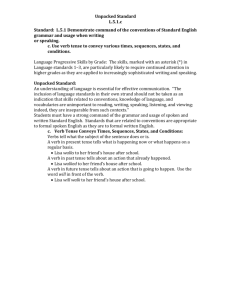

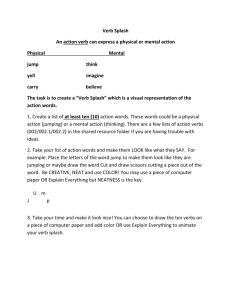

Common Patterns Of Error In First And Second Language Learning Leslie C. McIver University of Southern Mississippi FL 663 11/26/10 The question of how children acquire their first language has been the subject of linguistic research and debate for decades. Within the field of first language acquisition, there has been particular focus on the patterns of errors that children make in an attempt to trace language development. Many theorists maintain the existence of an innate model for language, known as Noam Chomsky’s theory of Universal Grammar (UG), and this model enables children to construct language, a theory is known as the innateness hypothesis (Fromkin, Rodman, Hyams , 330). Along with Chomsky, Stephen Krashen’s natural order hypothesis, which states that the acquisition of grammatical structures follows a ‘natural and predictable order’ (Krashen, 12), have both played a major role in both generativist and constructivist theories of the language acquisition. With regard to the natural order hypothesis, English has been the harbinger of most of the studies with regard to language acquisition. According to Roger Brown in his 1973 study, “children acquiring English as a first language tended to acquire certain grammatical morphemes, or function words, earlier than others” (Krashen, 12). Further studies of children learning English as a second language by Dulay (1974), Burt (1975), and Fathman (1975) revealed evidence of a ‘natural order’ of grammatical morphemes, despite their first language; in addition, Krashen states that although the order L1 and L2 acquisition principles are not identical, there are many similarities; Krashen cites unpublished studies of Russian and Spanish as second languages by Bruce (1979) and van Naerssen (1981) which confirm the natural order hypothesis (Krashen, 12-14). A child’s acquisition of morphology, modal auxiliaries, and the correct formation of wh questions are just a few of the patterns that linguists have studied in order to shape linguistic theories of the acquisition process in children. This essay will focus on the linguistic patterns of two children, both at different stages in their language development, who are both showing consistent linguistic patterns of errors that fall into the natural order of language acquisition. Understanding these linguistic patterns can be beneficial to the language teacher in that L2 learners tend to make the same types of errors in their language learning process: overgeneralization of regular verb forms, incorrect use of or substitution for modal auxiliaries, and syntactic errors in the formation of questions. Hodges’ Harbragce Handbook defines auxiliary verbs as those that “combine with other verbs to indicate tense, voice, or mood. Modal auxiliary verbs join the present form of the verb to make requests, give instructions, and express doubt, certainty, necessity, obligation, possibility, or probability” (Hodges, 76). Some examples of auxiliary verbs include the following: be, am, is, are was, were, been, being, have, has, had, do, does, and did. Modal auxiliary verbs, however, include shall, should, will, would, may, might, must, can, and could. The present tense use of the modals shall and will reflect the future tense while have combined with a verb in the past participle of a verb forms the perfect tense. Be can be combined with the present progressive form of a verb to reflect the present progressive tense (i.e. ing in English) or used with the past participle of a verb to form the passive voice (Hodges 77). The correct use of the auxiliaries do and does seem to be particularly difficult for children to master, perhaps because they can have very different, conflicting uses in English depending on the usage: one use of do and does can be combined with the present tense of a verb to convey emphasis (e.g. I do have 20 cats / Jane does have a big head). Interestingly, the inclusion of the latter requires a change in the conjugation of verb to have from has (used in the third person without the auxiliary of emphasis) to have (used in the third person with the auxiliary of emphasis). It is important to note that the third person usage requires this change while the first person use of do for emphasis does not require a change. To add to the confusion, both verbs are used in the formation of questions in English (e.g. Do you have rocks for brains? / Does your sister have man hands?). The data is a record of two weeks of observation of two preschool aged children. The first child observed is Miles, age 2;5, who makes consistent errors in the use of the modal auxiliaries can, may, and will. He also frequently neglects to use prepositions and articles resulting in phrases such as “give it me” and “I go store, too.” When using the past tense, he neglects to use it at all, resulting in utterances such as “I ring the doorbell” and “he say ‘hi’ me, mama” Alex, age 4;3, also shows consistent patterns of error. He frequently overgeneralizes irregular verb forms: Goed, sitted, eated, losted, wond, haded, bringed……. As many theorists agree that “L2 acquisition is like L1 acquisition,” these same patterns of errors are also often seen when learners are learning a second language; therefore, it is beneficial for language teachers understand some of the patterns of errors that are common in the acquisition of language. In a comparison of English and Spanish auxiliaries, there are some striking similarities. The acquisition of all of the auxiliary verbs and the modal auxiliary verbs, with the exception of shall, do, and does can be expressed in Spanish whether by utilizing a certain conjugation of the verb in a specific tense, the subjunctive, the conditional, and/or the future tense, or by placing one of the auxiliaries in juxtaposition to another verb, just like in English: puedo correr aquí. ” While English is the best studied language, it is not the only one studied. Research in order of acquisition for other language is beginning to emerge. As yet unpublished papers by Bruce (1979), dealing with Russian as a foreign language, and van Naerssen (1981), for Spanish as a foreign language, confirm the validity of the natural order hypothesis for other languages. Brown, R. (1973) A first language. Cambridge: Harvard Press. Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2011). An introduction to language, ninth edition. Wadsworth: Cengage Learning. Hodges, J., Horner, W., Webb, S., & Miller, R. (1998). Hodges’ harbrace handbook, thirteenth edition. New York: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and practice in second language. Internet edition. Accessed on 11/15/10. http://www.sdkrashen.com/Principles_and_Practice/index.html Krashen, S. and P. Pon (1975) An error analysis of an advanced ESL learner: the importance of the Monitor. Working Papers on Bilingualism 7: 125-129. Rowland, C., Pine, J., Lieven, E., & Theakston, A. (2005). The Incidence of Error in Young Children’s Wh-Questions. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 48: 384–404.