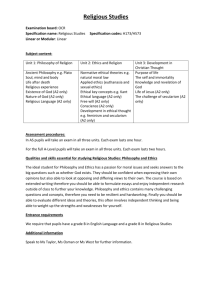

The Value of Philosophy

advertisement