Crucible Biographies

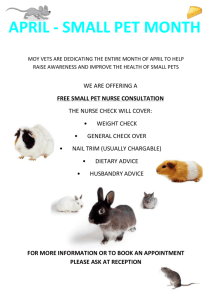

advertisement

Bridget Bishop Bridget Bishop, "a singular character, not easily described," was born sometime between 1632 and 1637. Bishop married three times. Her third and final marriage, after the deaths of her first two husbands, was to Edward Bishop, who was employed as a "sawyer" (lumber worker). She appears to have had no children in any of her marriages. Although Bishop had been accused by more individuals of witchcraft than any other witchcraft defendant (many of the accusations were markedly vehement and vicious), it was not so much her "sundry acts of witchcraft" that caused her to be the first witch hanged in Salem, as it was her flamboyant life style and exotic manner of dress. Despite being a member of Mr. Hale's Church in Beverly (she remained a member in good standing until her death), Bishop often kept the gossip mill busy with stories of her publicly fighting with her various husbands, entertaining guests in home until late in the night, drinking and playing the forbidden game of shovel board, and being the mistress of two thriving taverns in town. Some even went so far as to say that Bishop's "dubious moral character" and shameful conduct caused, "discord [to] arise in other familes, and young people were in danger of corruption." Bishop's blatant disregard for the respected standards of puritan society made her a prime target for accusations of witchcraft. In addition to her somewhat outrageous (by Puritan standards) lifestyle, the fact that Bishop "was in the habit of dressing more artistically than women of the village" also contributed in large part to her conviction and execution. She was described as wearing, "a black cap, and a black hat, and a red paragon bodice bordered and looped with different colors." This was a showy costume for the times. Aside from encouraging rumors and social disdain, this "showy costume" was used as evidence against her at her trial for witchcraft. In his deposition, Shattuck, the town dyer mentions, as corroborative proof of Bishop being a witch, that she used to bring to his dye house "sundry pieces of lace" of shapes and dimensions entirely outside his conceptions of what would be needed in the wardrobe of a plain and honest woman. Fashionable apparel was regarded by some as a "snare and sign of the devil." On April 18, 1692, when a warrant was issued for Bishop's arrest for witchcraft, she was no stranger to the courthouse. In 1680 she had been charged (but cleared) of witchcraft, and on other occasions she had ended up in the courthouse for violent public quarreling with her husband. Bishop had never seen or met any of her accusers until her questioning. While several of the afflicted girls cried out and writhed in the supposed pain she was causing them, John Hathorn and Jonathan Corwin questioned her, although there was little doubt in either of their minds as to her guilt: Q: Bishop, what do you say? You stand here charged with sundry acts of witchcraft by you done or committed upon the bodies of Mercy Lewis and Ann Putman and others. A: I am innocent, I know nothing of it, I have done no witchcraft .... I am as innocent as the child unborn. .... Q: Goody Bishop, what contact have you made with the Devil? A: I have made no contact with the Devil. I have never seen him before in my life. When asked by one of her jailers, Bishop claimed that she was not troubled to see the afflicted persons so tormented, and could not tell what to think of them and did not concern herself about them at all. But the afflicted girls were not Bishop's only accusers. Her sister's husband claimed that "she sat up all night conversing with the Devil" and that "the Devil came bodily into her." With a whole town against her, Bishop was charged, tried, and executed within eight days. On June 10, as crowds gathered to watch, she was taken to Gallows Hill and executed by the sheriff, George Corwin. She displayed no remorse and professed her innocence at her execution. Bishop's death did not go unnoticed in Salem. The court took a short recess, accusations slowed down for a time, more than a month passed before there were any more executions, and one of the judges, Nathaniel Saltonstall resigned, having become dissatisfied with the court's methods. Even Governor Phips had doubts about the methods of the court and went to Boston to consult the ministers there as to what should be done with the rest of the accused. Unfortunately for the eighteen others who would be hanged as witches (in addition to the one pressed to death and the several who died in prison), the ministers decidedly and earnestly recommended that the proceedings should be "vigorously carried on," and so they were. Less than a year after her death, Bishop's husband married Elizabeth Cash, and several of those who had testified against her, in deathbed confessions claimed that their accusations were "deluted by the Devil." –KS Sarah Good Sarah Good was the daughter of a prosperous Wenham innkeeper, John Solart. Solart took his own life in 1672 when Sarah was 17, leaving an estate of 500 pounds after debt. After testimony of an oral will, the estate was divided between his widow and her two eldest sons, with a portion to be paid to each of the seven daughters when they came of age. However, Mrs. Solart quickly remarried, her new husband came into possession of her share and the unpaid shares of the daughters, and as a result, most of the daughters never received a portion of the Solart estate. Sarah married a former indentured servant, Daniel Poole. Poole died sometime after 1682, leaving Sarah only debts, which some sources credit her with creating for Poole. Regardless of the cause of the debt, Sarah and her second husband, William Good, were held responsible for paying it. A portion of their land was seized and sold to satisfy their creditors, and shortly thereafter they sold the rest of their land, apparently out of dire necessity. By the time of the trials, Sarah and her husband were homeless, destitute and she was reduced to begging for work, food, and shelter from her neighbors. Good was one of the first three women to be brought in at Salem on the charge of witchcraft, after having been identified as a witch by Tituba. She fit the prevailing stereotype of the malefic witch quite well. Good's habit of scolding and cursing neighbors who were unresponsive to her requests for charity generated a wealth of testimony at her trials. At least seven people testified as to her angry muttering and general turbulence after the refusal of charity. Particularly damaging to her case, was her accusation by her daughter. Four- year-old Dorcas Good (Sarah's only child) was arrested on March 23, gave a confession, and in so doing implicated her mother as a witch. At the time of her trial, Good was described as "a forlorn, friendless, and forsaken creature, broken down by wretchedness of condition and ill-repute." She has been called "an object for compassion rather than punishment." The proceedings against Good were described as "cruel, and shameful to the highest degree." This remark must have been due in part to the fact that some of the spectral evidence against Good was known to be false at the time of her examination. During the trial, one of the afflicted girls cried out that she was being stabbed with a knife by the apparition of Good. Upon examination, a broken knife was found on the girl. However, as soon as it was shown to the court, a young man came forward with the other part of the knife, stated that he had broken it yesterday and had discarded it in the presence of the afflicted girls. Although the girl was reprimanded and warned not to lie again, the known falsehood had no effect on Good's trial. She was presumed guilty from the start. It has been said that "there was no one in the country around against whom popular suspicion could have been more readily directed, or in whose favor and defense less interest could be awakened." Good was executed on July 19. She failed to yield to judicial pressure to confess, and showed no remorse at her execution. In fact, in response to an attempt by Minister Nicholas Noyes to elicit a confession, Good called out from the scaffolding, "You are a liar. I am no more a witch than you are a wizard, and if you take away my life God will give you blood to drink." Her curse seems to have come true. Noyes died of internal hemorrhage, bleeding profusely at the mouth. Despite the seemingly effectiveness of her curse, it likely just further convinced the crowds of her guilt. Although he clearly deserved nothing, since he was an adverse witness against his wife and did what he could to stir up the prosecution against her, William Good was given one of the larger sums of compensation from the government in 1711. He did not swear she was a witch, but what he did say tended to prejudice the magistrates and public against her. The reason for his large settlement was his connections with the Putnam family. Although Good's daughter was released from prison after the trials, William Good claimed she was permanently damaged from her stay in chains in the prison, and that she was never useful for anything. –KS Now compare the biographies of Rebecca Nurse, John Proctor, and Giles Corey. Create a Venn diagram and answer the following questions: 1.What do they have in common? 2.How are they alike or different from the first two defendants? 3. Can we draw any conclusions about what things could get one accused of witchcraft in Salem in the fifteenth century? Rebecca Nurse "The Trial of Rebecca Nurse" Rebecca Nurse was the daughter of William Towne, of Yarmouth, Norfolk County, New England where she was baptized Feb. 21, 1621. Her sister Mary (also accused and put to death for witchcraft) married Isaac Easty. Another sister, Sarah Cloyce, was also accused of witchcraft. Nurse's husband was described as a "traymaker." The making of these articles and similar articles of domestic use was important employment in the remote countryside. He seems to have been highly respected by his neighbors, and more often than anyone else was called in to settle disputes. Nurse had four sons and four daughters. Nurse was one of the first "unlikely" witches to be accused. At the time of her trial she was 71 years old, and had "acquired a reputation for exemplary piety that was virtually unchallenged in the community." It was written of Nurse: "This venerable lady, whose conversation and bearing were so truly saint-like, was an invalid of extremely delicate condition and appearance, the mother of a large family, embracing sons, daughters, grandchildren, and one or more greatgrand children. She was a woman of piety, and simplicity of heart." That her reputation was virtually unblemished was evidenced by the fact that several of the most active accusers were more hesitant in their accusations of Nurse, and many who had kept silent during the proceedings against others, came forward and spoke out on behalf of Nurse, despite the dangers of doing so. Thirty-nine of the most prominent members of the community signed a petition on Nurse's behalf, and several others wrote individual petitions vouching for her innocence. One of the signers of the petition, Jonathan Putnam, had originally sworn out the complaint against Nurse, but apparently had later changed his mind on the matter of her guilt. (LINK TO DOCUMENTS RELATING TO NURSE TRIAL) Unlike many of the other accused, during the questioning of Nurse, the magistrate showed signs of doubting her guilt, because of her age, character, appearance, and professions of innocence. However, each time he would begin to waiver on the issue, someone else in the crowd would either heatedly accuse her or one of the afflicted girls would break into fits and claim Nurse was tormenting her. Upon realizing that the magistrate and the audience had sided with the afflicted girls Nurse could only reply, " I have got nobody to look to but God." She then tried to raise her hands, but the afflicted girls fell into dreadful fits at the motion. At Nurse's trial on June 30, the jury came back with a verdict of "Not Guilty." When this was announced there was a large and hideous outcry from both the afflicted girls and the spectators. The magistrates urged reconsideration. Chief Justice Stoughton asked the jury if they had considered the implications of something Nurse had said. When Hobbs had accused Nurse, Nurse had said "What do you bring her? She is one of us." Nurse had only meant that Hobbs was a fellow prisoner. Nurse, however, was old, partially hard of hearing, and exhausted from the day in court. When Nurse was asked to explain her words "she is one of us," she did not hear the question. The jury took her silence as an indication of guilt. The jury deliberated a second time and came back with a verdict of guilty. Shocking as it seems today, it was not uncommon in the seventeenth century for a magistrate to ask the jury to reconsider its verdict. Her family immediately did what they could to rectify the mistake that had caused her to be condemned, but it was no use. Nurse was granted a reprieve by Governor Phips, however no sooner had it been issued, than the accusers began having renewed fits. The community saw these fits as conclusive proof of Nurse's guilt. On July 3, this pious, God fearing woman was excommunicated from her church in Salem Town, without a single dissenting vote, because of her conviction of witchcraft. Nurse was sentenced to death on June 30. She was executed on July 19. Public outrage at her conviction and execution have been credited with generating the first vocal opposition to the trials. On the gallows Nurse was "a model of Christian behavior," which must have been a sharp contrast to Sarah Good, another convicted witch with whom Nurse was executed, who used the gallows as a platform from which to call down curses on those who would heckle her in her final hour. It was not until 1699 that members of the Nurse family were welcomed back to communion in the church, and it was fifteen years later before the excommunication of Nurse was revoked. In 1711, Nurse's family was compensated by the government for her wrongful death.--KS John Proctor Proctor was originally from Ipswich, where he and his father before him had a farm of considerable value. In 1666 he moved to Salem, where he worked on a farm, part of which he later bought. Proctor seems to have been an enormous man, very large framed, with great force and energy. Although an upright man, he seems to have been rash in speech, judgment, and action. It was his unguarded tongue that would eventually lead to his death. From the start of the outbreak of witchcraft hysteria in Salem, Proctor had denounced the whole proceedings and the afflicted girls as a scam. When his wife was accused and questioned, he stood with her throughout the proceedings and staunchly defended her innocence. It was during her questioning that he, too, was named a witch. Proctor was the first male to be named as a witch in Salem. In addition, all of his children were accused. His wife Elizabeth, and Elizabeth's sister and sisterin-law, also were accused witches. Although tried and condemned, Elizabeth avoided execution because she was pregnant. Mary Warren, the twenty-year-old maid servant in the Proctor house--who herself would later be named as a witch--accused Proctor of practicing witchcraft. It is believed by some sources that when Mary first had fits Proctor, believing them to be fake, would beat her out of them. Even if it didn't actually beat her, he certainly threatened beatings and worse if she didn't stop the fits. It was this type of outspoken criticism of the afflicted that caused Proctor to be accused. Proctor was tried on August 5 and hanged on the 19th. While in prison on July 23, Proctor wrote a letter to the clergy of Boston, who were known to be uneasy with the witchcraft proceedings. In his letter he asked them to intervene to either have the trials moved to Boston or have new judges appointed. After the trial and execution of Rebecca Nurse, the prospects of those still in prison waiting trial were grim. If a person with a reputation as untarnished as hers could be executed, there was little hope for any of the other accused, which is why Proctor made his request. With the present judges, who were already convinced of guilt, the trial would just be a formality. In response to Proctor's letter, in which he describes certain torture that was used to elicit confessions, eight ministers, including Increase Mather, met at Cambridge on August 1. Little is known about this meeting, except that when they had emerged, they had drastically changed their position on spectral evidence. The ministers decided in the meeting that the Devil could take on the form of innocent people. Unfortunately for Proctor, their decision would not have widespread impact until after his execution. Proctor pleaded at his execution for a little respite of time. He claimed he was not fit to die. His plea was, of course, unsuccessful. In seventeenth-century society, it would not have been uncommon for a man so violently tempered as Proctor to feel that he had not yet made peace with his fellow man or his God. In addition, it is thought that he died inadequately reconciled to his wife, since he left her out of the will that he drew up in prison. Proctor's family was given 150 pounds in 1711 for his execution and his wife's imprisonment. Giles Corey Giles Corey was a prosperous farmer and full member of the church. He lived in the southwest corner of Salem village. In April of 1692, he was accused by Ann Putnam, Jr., Mercy Lewis, and Abigail Williams of witchcraft. Ann Putnam claimed that on April 13 the specter of Giles Corey visited her and asked her to write in the Devil's book. Later, Putnam was to claim that a ghost appeared before her to announce that it had been murdered by Corey. Other girls were to describe Corey as "a dreadful wizard" and recount stories of assaults by his specter. Why Corey was named as a witch (male witches were generally called "wizards" at the time) is a matter of speculation, but Corey and his wife Martha were closely associated with the Porter faction of the village church that had been opposing the Putnam faction. Corey, eighty years old, was also a hard, stubborn man who may have expressed criticism of the witchcraft proceedings. Corey was examined by magistrates on April 18, then left to languish with his wife in prison for five months awaiting trial. When Corey's case finally went before the grand jury in September, nearly a dozen witnesses came forward with damning evidence such as testimony that Corey was seen serving bread and wine at a witches' sacrament. Corey knew he faced conviction and execution, so he chose to refuse to stand for trial. By avoiding conviction, it became more likely that his farm, which Corey recently deeded to his two sons-in-law, would not become property of the state upon his death. The penalty for refusing to stand for trial was death by pressing under heavy stones. It was a punishment never before seen in the colony of Massachusetts. On Monday, September 19, Corey was stripped naked, a board placed upon his chest, and then--while his neighbors watched--heavy stones and rocks were piled on the board. Corey pleaded to have more weight added, so that his death might come quickly. Samuel Sewall reported Corey's death: "About noon, at Salem, Giles Corey was press'd to death for standing mute." Robert Calef, in his report of the event, added a gruesome detail: Giles's "tongue being prest out of his mouth, the Sheriff with his cane forced it in again, when he was dying." Judge Jonathan Corwin ordered Corey buried in an unmarked grave on Gallows Hill. Corey is often seen as a martyr who "gave back fortitude and courage rather than spite and bewilderment." His very public death may well have played in building public opposition to the witchcraft trials.