TUaS-Sci-Com-Tools-workshop-

advertisement

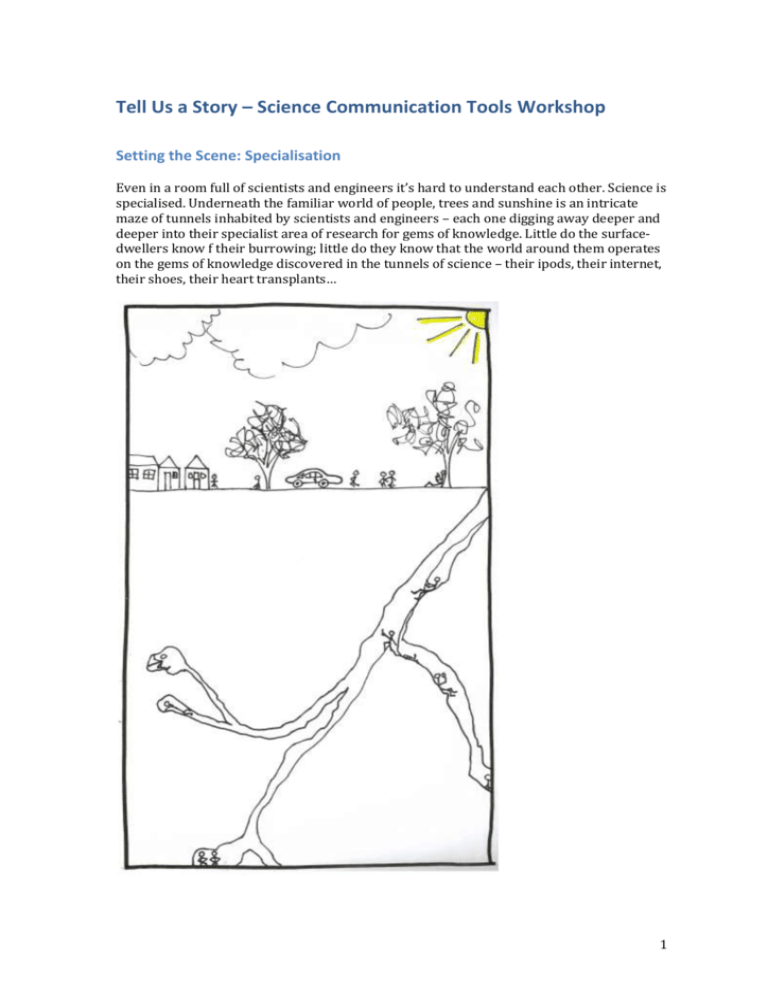

Tell Us a Story – Science Communication Tools Workshop Setting the Scene: Specialisation Even in a room full of scientists and engineers it’s hard to understand each other. Science is specialised. Underneath the familiar world of people, trees and sunshine is an intricate maze of tunnels inhabited by scientists and engineers – each one digging away deeper and deeper into their specialist area of research for gems of knowledge. Little do the surfacedwellers know f their burrowing; little do they know that the world around them operates on the gems of knowledge discovered in the tunnels of science – their ipods, their internet, their shoes, their heart transplants… 1 As the scientists and engineers dig they learn a new language of symbols, jargon and strange and complicated concepts. You could say they’re learning the language of Nature so they can ask questions and hear the answers. But when they come to the surface it is completely incomprehensible: So, Your Mission as a Science Communicator is to climb up the tunnel from your specialised area of research to the surface and learn to talk about what you do in a way the surface dwellers will understand and relate to. 2 Why is science communication important? Change the world Evidence-based policy Get a good job! Get funding! To combat sensationalist media Establish dialogue around science Improve image of scientists in society Workshop Outcomes: A toolbox of techniques for communicating specialist science with lay audiences Inspiration and ideas for your stories Key Messages: Put the people back in! Think of your audience – why should they care? Your emotion is the key to audience engagement Communication is 2-way - be yourself – open and genuine Content: 1. Four techniques to communicate specialist concepts with your target audience: a. Application b. Metaphor c. Emotion d. Story 2. Language tips Your Tool Kit: Four ways to communicate specialist concepts with lay audiences: Tool 1 - Application Key Question: How does your research affect your audience? Why should they care? The golden question! Choose an application the audience cares about KEEP IT SIMPLE! Exercise 1: Choose your audience: The first thing to do in any science communication project is to define your audience. Who are you talking to? In any science communication project – story, presentation, and article – it helps to have one person in mind that you’re talking to. Who is your target audience? Who do you want to receive your message? Choose someone that doesn’t know much about your topic but that you feel comfortable talking to. It could be an aunty, friend, daughter, cousin… 3 Draw your chosen person in the circle below and brainstorm about them around the outside. What are they interested in? Where do they come from? Where do they work? What are their daily concerns? What are their favourite places? Your audience 4 Audience Focus! Think about what’s important for your audience first then introduce your research. Examples: The following two examples are the opening sentences of two articles I recently wrote for a booklet on supercomputing in New Zealand. The aim f the booklet was to persuade the government to fund more supercomputers so I chose the Minister for Science and Technology, Wayne Mapp for my audience. I studied his speeches to learn which language and concepts are important to him. 1. If investment bankers had been modelling the US real estate markets using supercomputers we might have avoided the recent credit crisis. 2. "If we can detect breast cancer in a small enough state, which isn't possible at the moment, it's effectively a cure" Eli Van Houten Notice how in both examples I started with a concept the audience (Mapp) would care about (credit crisis and cancer) and then introduced the supercomputers. Think about what’s important to your audience first – then introduce the science Exercise 2: Applications Take a few minutes to think about how your research relates to your audience. How could it impact their daily life? Why should they care? Research 5 When you’ve thought of a way that your research applies to your audience, write a couple of sentences to introduce the idea to them. Limitations of Applications: Focussing on the applications of research emphasises breakthroughs rather than the process, the wonder or details of science Difficult for blue sky research 6 Tool 2 - Metaphors: Bridges to Understanding Metaphor is a broad term encompassing similes, personification and analogies. They are extremely powerful in science communication because they use concepts the audience is familiar to explain unfamiliar concepts. Metaphor: A figure of similarity - substitutes for the thing, something it is like. eg. DNA is the blueprint for life; the brain is a computer. Simile: Compares one thing with an other - eg the moon is like an apple. Personification: The attribution of a personal nature or human characteristics to something nonhuman. Analogies: Drawn out metaphors used to compare and contrast two phenomenon. Metaphors frame the subject in a particular way, which causes the audience to ask particular questions. For example if you say the brain is a computer, the audience will ask questions like “how do you fix it when it breaks down?” and “how does the hardware work?” It’s important to choose the right metaphor that prompts the audience to ask the right questions. Metaphors can go straight from the tip of the tunnel to the audience in one step! Exercise 3: Personification 1. Choose an aspect of your research to personify 2. Get into groups of 3 or 4 3. Personified character introduces him (or her)self 4. Other members of the group ask questions: Where do you live? What are your surroundings like - what do they smell like, feel like, look like, sound like? What do you desire most in life? What drives you? What repels you? Do you live with anyone else? How do you get along? How do you get around? Do you have a vehicle? How would you describe your personality? Example: Metaphors The following example comes from a wonderful science communicator in Christchurch – Hannah Farr. She’s a chemical engineer studying blood flow in the brain. She sees her role as a research as listening in to the conversations between the different parts of the brain and translating them into language we can understand. Her research helps in the understanding of diseases like Alzheimers and Strokes. The following slides show a personified conversation between neurons, astrocytes and blood vessels. 7 8 Tool 3: Emotion Your emotion is the key to audience engagement! Passion Wonder & Excitement are contagious. Science is full of emotion Put the emotion and the people back in the science! People don’t act on information alone – they act on how they feel about that information Emotion motivates people to action! Tool 4: Story Research shows that our brains interpret our feelings, actions and experiences in the form of stories. Neuroscientist, Michael Gazzaniga believes stories are what give us a sense of unified self. Stories evoke emotion that motivates people to action. Narrative Structure: The Bulgarian linguist Tzetan Todorov identified five stages to any narrative: A. B. C. D. E. Initial equilibrium. Disruption of equilibrium by some action. Recognition of the disruption Attempt to repair the disruption Reinstatement of equilibrium (different to initial state) Characterisation Russian theorist Vladimir Propp analysed 100 folk tales and discovered different character types: The Hero The villain – deceives the hero and commits an act of harm The helper – helps the hero in his quest The princess (the object the hero is seeking) Exercise 4: Narrative Use the Narrative Structure above to create a story around your research. See if any of the character types fit too. 9 A B C D E Language tips: Golden Rule: Express actions as verbs and characters as the subjects of those verbs. 10 Replace "passive voice" with "active voice" Bring back the personal pronouns!! Examples : Characters and Actions ”Once upon a time, there was Little Red Riding Hood, Grandma, the Woodsman and the wolf. The end.” It has characters but no actions. Now, this story: “Once upon a time, as a walk through the woods was taking place, a jump out from behind a tree occurred, causing fright.” There’s plenty of action in this story but no characters. So, let’s bring characters and actions together: “Once upon a time, as a walk through the woods was taking place on the part of Little Red Riding Hood, the wolf’s jump out from behind a tree occurred, causing fright in Little Red Riding Hood.” So, now, the story has actions and characters but it feels dense and plodding. That’s because the actions (the walk, the jump and fright) are expressed as nouns and not as verbs. So, express actions as verbs and characters as the subjects of those verbs: “Once upon a time, Little Red Riding Hood was walking through the woods, when the wolf jumped out from behind a tree and frightened her.” 11