Lesson on the War of American Independence and George

advertisement

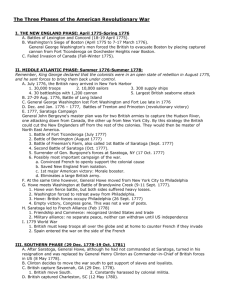

American Military History, Topic 4: The War of American Independence and George Washington’s Circular Letter (1780) Background: The War of American Independence (1775-1783) secured by force of arms the social, cultural, and political reconstitution that had accelerated and matured between the end of the French and Indian War and the adoption of the Declaration of Independence: the real American Revolution that had occurred in Americans’ hearts and minds. Leaving the “Empire of Liberty” with its honored heritage of constitutional monarchy, individual rights, and common law—not to mention its imperial splendor and vast riches—for the promise of even greater liberty in a new republican experiment had not been an easy decision, but, by the bloodletting at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, most English colonists in North America had given up demanding their rights as Englishmen and created a separate identity as Americans. As veteran Levi Preston famously explained years after the conflict, “What we meant in going for those Redcoats was this: we had always been free, and we meant to be free always. They didn’t mean we should.” Indeed, Thomas Paine, whose Common Sense helped to sever the last link to Britain—the King—spoke for most Americans (Loyalists, who constituted one-fifth to one-third of the population, excepting) when he said that the war “contributed more to enlighten the world, and diffuse a spirit of freedom and liberality among mankind, than any human event that ever preceded it.” Scriptures of the Restoration confirm that the “power of God was with [the colonists]”, that they “were delivered by the power of God”, and that their deliverance in the war “redeemed the land by the shedding of blood” to create a nation where the Constitution could be established and maintained for the “rights and protection of all flesh, according to just and holy principles,” which would allow the Restoration to occur and flourish in the latter days. Two hundred thousand Continentals and militiamen gave their time—and over 25,000 of them (.9 percent of the total population, compared to 1.6 percent in the American Civil War—America’s bloodiest war—and over 12 percent of those who bore arms, as compared to 13 percent in the American Civil War) gave their lives for the cause of American independence, and the casualty rate of those who served in the Continental Army, a group that accounted for more than half of all Americans who fought, was between 30 and 40 percent: the highest of any war in American history. Over the course of eight bloody years, an often ill-funded, ill-equipped, and ill-trained force of Continentals and militia—aided by the power of God and, from 1778, the French—made recovering the thirteen colonies too costly for the British Empire and its vaunted professional army: the dominant military power in the world. Between 1775 and 1778, the two sides battled mostly in the American North. The British won battles at Quebec in Canada (December 1775), Brooklyn Heights and White Plains in New York (August, October 1776), and Brandywine Creek in Pennsylvania (September 1777), while the Americans scored victories at Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga in New York (May 1775, September-October 1777), Trenton and Princeton in New Jersey (December 1776, January 1777), and Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Vincennes on the northwestern frontier (June-July 1778). They also fought to contested outcomes at Lexington and Concord and Breed’s Hill (“Bunker Hill”) in Massachusetts (April, June 1775) and Monmouth Court House in New Jersey (June 1778). Beginning in 1778, the American Military History, Topic 4: The War of American Independence and George Washington’s Circular Letter (1780) course of the conflict moved to the American South, where it would remain until the decisive victory at Yorktown in 1781. The British defeated the Americans at Savannah in Georgia (December 1778, September-October 1779) and Charleston and Camden in South Carolina (February-May 1780, August 1780), while the Americans took the field at Kettle Creek in Georgia (February 1779), King’s Mountain and Cowpens in South Carolina (October 1780, January 1781), and Yorktown in Virginia (August-October 1781). The two armies also fought to a contested decision at Guilford Court House in North Carolina (March 1781). The war had three major turning points that led to American victory: Trenton, Saratoga, and Yorktown. Despite Britain having the greatest navy, best-equipped army, most professional training and structure of command, and the deep pockets of the most powerful empire in the world—and despite America fighting while simultaneously trying to create a new army and a new government—Americans were fighting on their own land to defend their own homes and families and were motivated by the idea of liberty. British troops were professional soldiers doing the bidding of empire-builders in London, and, as the Americas proved at Trenton, Saratoga, and Yorktown, the British could not “defeat an idea with an army” (Thomas Paine). Washington’s determined crossing of an ice-choked Delaware River to surprise victory at Trenton on 26 December 1776 saved and inspired an army that had lost 90 percent of its strength and every major engagement over the previous five months. At Saratoga in September and October 1777, General Horatio Gates shockingly pinned General John Burgoyne’s troops after fighting at Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights, which forced Burgoyne to surrender and convinced the French, who had been providing clandestine aid since 1776, to ally openly with the Americans. At Yorktown in August-October 1781, the Franco-American alliance finally—for the first and only time—worked as hoped, and a perfectly executed operation—which timed a convergence of Washington’s and Count Jean Baptiste de Rochambeau’s infantry from New York with the Marquis de Lafayette’s infantry and Admiral Francois Joseph Paul de Grasse’s fleet along the coast of Virginia—trapped General Charles Cornwallis, forcing him to surrender, prompting his military band to play “The World Turned Upside Down”, and causing British strategists in London to realize that the warring colonies were now “lost forever.” Though British forces continued to hold Savannah, Charleston, Wilmington, and New York, and though a few skirmishes threatened to reignite widespread conflict, within two years Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay orchestrated the Treaty of Paris with Great Britain, France, and Spain, which officially acknowledged the freedom, sovereignty, and independence of the United States, granted the U. S. most of the area east of the Mississippi, gave Spain (which had declared war against Britain in 1779) East and West Florida, and confined Britain to Canada. American independence—and, with it, a new experiment in republicanism dedicated to self-government, contract theory, virtue, Godgiven rights, and equality of opportunity—had been secured and granted room to grow. American Military History, Topic 4: The War of American Independence and George Washington’s Circular Letter (1780) Questions to Consider as You Read: What does Washington say about the challenges of temporary enlistments? What does Washington say about the challenges of militia units? What does Washington say about the challenges of finances and equipment? Research: Washington’s Circular Letter to the States (18 October 1780) As you read, don’t forget to mark and annotate main ideas, key terms, confusing concepts, unknown vocabulary, cause/effect relationships, examples, etc. I am religiously persuaded, that the duration of the war, and the greatest part of the misfortunes and perplexities we have hitherto experienced are chiefly to be attributed to the system of temporary enlistments. Had we in the commencement raised an army for the war, such as was within the reach of the abilities of these States to raise and maintain, we should not have suffered those military checks which have so frequently shaken our cause, nor should we have incurred such enormous expenditures as have destroyed our paper currency, and with it all public credit. A moderate compact force on a permanent establishment, capable of acquiring the discipline essential to military operations, would have been able to make head against the enemy without comparison better than the throngs of militia, which at certain periods have been, not in the field, but in their way to and from the field; for from that want of perseverance which characterizes all militia, and of that coercion which cannot be exercised upon them, it has always been found impracticable to detain the greatest part of them in service, even for the term for which they have been called out, and this has been commonly so short, that we have had a great proportion of the time two sets of men to feed and pay, one coming to the army, and the other going from it. From this circumstance, and from the extraordinary waste and consumption of provisions, stores, camp equipage, arms, clothes, and every other article incident to irregular troops, it is easy to conceive what an immense increase of public expense has been produced from this source, of which I am speaking. I might add the diminution of our agriculture, by calling off at critical seasons the laborers employed in it, as has happened in instances without number…. America has been almost amused out of her liberties. We have frequently heard the behavior of the militia extolled upon one and another occasion, by men who judge only from the surface, by men who had particular views in misrepresenting, by visionary men whose credulity easily swallowed every vague story in support of a favorite hypothesis. I solemnly declare, I never was witness to a single instance that can countenance an opinion of militia or raw troops being fit for the real business of fighting. I have found them useful as light parties to skirmish in the woods, but incapable of making or sustaining a serious attack. This firmness is only acquired by habit of discipline and service. I mean not to detract from the merit of the militia—their zeal and spirit upon a variety of occasions have entitled them to the highest applause; but it is of the American Military History, Topic 4: The War of American Independence and George Washington’s Circular Letter (1780) greatest importance we should learn to estimate them rightly. We may expect every thing from ours that militia is capable of, but we must not expect from any, services for which regulars alone are fit. The late battle of Camden is a melancholy comment upon this doctrine. The militia fled at the first fire, and left the continental troops surrounded on every side and overpowered by numbers, to combat for safety instead of victory. The enemy themselves have witnessed to their valor…. Our finances are in an alarming state of derangement. Public credit is almost arrived at its last stage. The people begin to be dissatisfied with the feeble mode of conducting the war, and with the ineffectual burdens imposed upon them, which though light in comparison with what other nations feel, are from their novelty heavy to them. They lose their confidence in government apace. The army is not only dwindling into nothing, but the discontent of the officers as well as the men have matured to a degree that threatens but too general a renunciation of the service, at the end of the campaign. Since January last, we have had registered at Head Quarters, more than one hundred and sixty resignations, besides a number of others that never were regularly reported. I speak of the army in this quarter. We have frequently in the course of the campaign, experienced an extremity of want. Our officers are in general indecently defective in clothing— our men are almost naked, totally unprepared for the inclemency of the approaching season. We have no magazines for the winter —the mode of procuring our supplies is precarious, and all the reports of the officers employed in collecting them are gloomy.1 Notebook Questions: Reason and Record • What does Washington say about the challenges of temporary enlistments? • What does Washington say about the challenges of militia units? • What does Washington say about the challenges of finances and equipment? 1 SOURCE: Ford, Worthington C., ed. The Writings of George Washington, vol 8. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890. American Military History, Topic 4: The War of American Independence and George Washington’s Circular Letter (1780) Notebook Questions: Relate and Record • How does the document relate to FACE Principle #7: The Christian Principle of American Political Union: “Internal agreement or unity, which is invisible, produces an external union, which is visible in the spheres of government, economics, and home and community life. Before two or more individuals can act effectively together, they must first be united in spirit in their purposes and convictions”? • How does the document relate to 1 Nephi 13:16-19? Record Activity: Multiple Choice Comprehension Check 1. Background: All of the following are true about the War of American Independence except which one? a. It secured by force of arms the social, cultural, and political reconstitution that was the real American Revolution. b. One-fifth to one-third of Americans did not support it. c. It “redeemed the land by the shedding of blood” to create a nation where the Constitution could be established and maintained for the “rights and protection of all flesh, according to just and holy principles,” which would allow the Restoration to occur and flourish in the latter days. d. Between 1775 and 1783, .9 percent of the total population and over 12 percent of those who bore arms gave their lives in it. e. It caused Great Britain, France, and Spain to officially acknowledge the freedom, sovereignty, and independence of the United States. f. It granted the U. S. most of the area west of the Mississippi. g. It gave Spain (which had declared war against Britain in 1779) East and West Florida. h. It confined Britain to Canada. American Military History, Topic 4: The War of American Independence and George Washington’s Circular Letter (1780) 2. Background: Which one of the following answers correctly pairs turning points of the War of American Independence with corresponding descriptions? a. Trenton = 1776, salvation and inspiration; Saratoga = 1777, French alliance; Yorktown = 1781, decisive victory b. Saratoga = 1776, decisive victory; Trenton = 1781, French alliance; Yorktown = 1777, salvation and inspiration c. Yorktown = 1776, French alliance; Trenton = 1781, decisive victory; Saratoga = 1777, salvation and inspiration 3. Source: Which of the following are true about Washington’s views of American militia units? a. They were too often coming and going from the battlefield—rather than fighting in it. b. They were characterized by a want of perseverance. c. Coercion could not be exercised upon them. d. It was impractical to detain the greatest part of them in service—even for the term for which they were called. e. They wasted and consumed too many provisions and, therefore, caused an immense increase in public expense. f. They were not fit for the real business of fighting because they were incapable of making or sustaining serious attacks. g. They could not provide the same service as regulars, but they did have zeal and spirit. h. Camden was their finest hour. i. a, b, c, d, and e j. f, g, and h k. all but two l. all but one m. all of the above