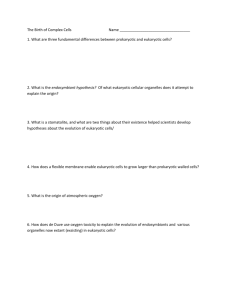

Prokaryotes to Eukaryotes: Evolution & Endosymbiosis

From prokaryotes to eukaryotes

Living things have evolved into three large clusters of closely related organisms, called "domains":

Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota.

Archaea and Bacteria are small, relatively simple cells surrounded by a membrane and a cell wall, with a circular strand of DNA containing their genes. They are called prokaryotes.

Virtually all the life we see each day

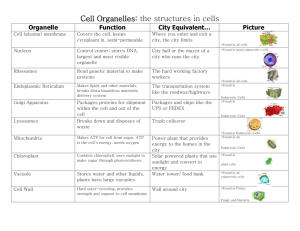

— including plants and animals — belongs to the third domain, Eukaryota. Eukaryotic cells are more complex than prokaryotes, and the DNA is linear and found within a nucleus. Eukaryotic cells boast their own personal "power plants", called mitochondria . These tiny organelles in the cell not only produce chemical energy, but also hold the key to understanding the evolution of the eukaryotic cell.

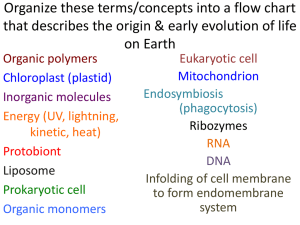

The complex eukaryotic cell ushered in a whole new era for life on Earth, because these cells evolved into multicellular organisms. But how did the eukaryotic cell itself evolve?

How did a humble bacterium make this evolutionary leap from a simple prokaryotic cell to a more complex eukaryotic cell? The answer seems to be symbiosis — in other words, teamwork.

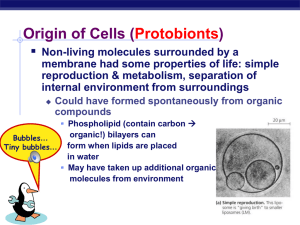

Evidence supports the idea that eukaryotic cells are actually the descendents of separate prokaryotic cells that joined together in a symbiotic union. In fact, the mitochondrion itself seems to be the "great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great granddaughter" of a free-living bacterium that was engulfed by another cell, perhaps as a meal, and ended up staying as a sort of permanent houseguest. The host cell profited from the chemical energy the mitochondrion produced, and the mitochondrion benefited from the protected, nutrient-rich environment surrounding it. This kind of "internal" symbiosis — one organism taking up permanent residence inside another and eventually evolving into a single lineage — is called endosymbiosis.

Evidence for endosymbiosis

Biologist Lynn Margulis first made the case for endosymbiosis in the 1960s, but for many years other biologists were skeptical. Although Jeon watched his amoebae become infected with the x-bacteria and then evolve to depend upon them, no one was around over a billion years ago to observe the events of endosymbiosis. Why should we think that a mitochondrion used to be a free-living organism in its own right? It turns out that many lines of evidence support this idea. Most important are the many striking similarities between prokaryotes (like bacteria) and mitochondria:

Membranes — Mitochondria have their own cell membranes, just like a prokaryotic cell does.

DNA — Each mitochondrion has its own circular DNA genome, like a bacteria's genome, but much smaller. This DNA is passed from a mitochondrion to its offspring and is separate from the "host" cell's genome in the nucleus.

Reproduction — Mitochondria multiply by pinching in half — the same process used by bacteria. Every new mitochondrion must be produced from a parent mitochondrion in this way; if a cell's mitochondria are removed, it can't build new ones from scratch.

When you look at it this way, mitochondria really resemble tiny bacteria making their livings inside eukaryotic cells! Based on decades of accumulated evidence, the scientific community supports Margulis's ideas: endosymbiosis is the best explanation for the evolution of the eukaryotic cell.

What's more, the evidence for endosymbiosis applies not only to mitochondria, but to other cellular organelles as well.

Chloroplasts are like tiny green factories within plant cells that help convert energy from sunlight into sugars, and they have many similarities to mitochondria. The evidence suggests that these chloroplast organelles were also once free-living bacteria.

The endosymbiotic event that generated mitochondria must have happened early in the history of eukaryotes, because all eukaryotes have them. Then, later, a similar event brought chloroplasts into some eukaryotic cells, creating the lineage that led to plants.

Despite their many similarities, mitochondria (and chloroplasts) aren't free-living bacteria anymore. The first eukaryotic cell evolved more than a billion years ago. Since then, these organelles have become completely dependent on their host cells. For example, many of the key proteins needed by the mitochondrion are imported from the rest of the cell. Sometime during their long-standing relationship, the genes that code for these proteins were transferred from the mitochondrion to its host's genome.

Scientists consider this mixing of genomes to be the irreversible step at which the two independent organisms become a single individual.