Ians-Latest

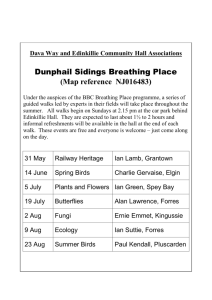

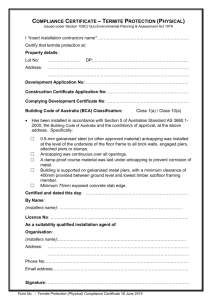

advertisement