Full Text (Final Version , 14mb)

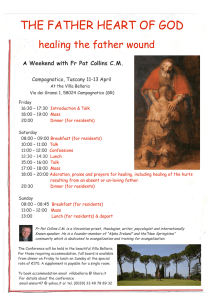

advertisement