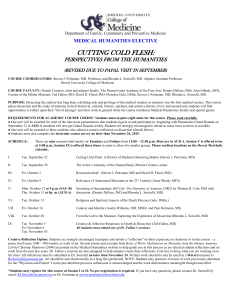

instructors in *cutting cold flesh* introduce their hours

advertisement

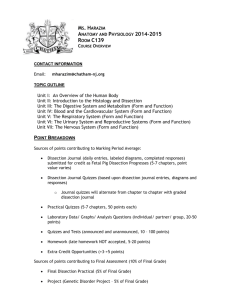

INSTRUCTORS IN “CUTTING COLD FLESH” INTRODUCE THEIR HOURS 2014 (With some added comments from the course directors) Steven J. Peitzman: “A History of Students Dissecting Bodies” Friday, September 19, 2014 in AUD A In the realms of the history and sociology of medicine, of late it’s bodies everywhere, especially the afterlife of bodies. New books on the history and cultural meaning of dissection abound, from deep scholarship to lurid novels of body-snatching. Plastinated bodies tour the globe, attracting paying customers and controversy. Is our course merely catching up with these enthusiasms? No! We’ve been doing Cutting Cold Flesh since 1999. The historians, novelists, and plastinators are catching up with us. Curiously, the recent historical and “cultural” passion for dissection and body-study comes at a time when the enduring site for anatomization―the medical school gross lab―in many places struggles for time and attention. Some schools have greatly reduced hands-on dissection, or even eliminated it. (A few art schools, such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, still offer their students the opportunity to dissect, or at least view dissections). Not long ago, however, medical students went to what we might call, let us say, considerable trouble to obtain their “material” and dissect. They did so for a variety of good reasons, but they knew that this work at least borders on, if not crosses into, the transgressive and outrageous. Not surprisingly, students wrote about dissection in letters and memoirs, and when they came to have cameras, they photographed themselves, with their cadavers, to document this passage in their lives and careers. And with our course, we hope to evoke and explore the experience, and expand understanding. Patrick Connors: “The Artist’s Anatomy of the Human Body” Tuesday, September 23, 2014 in AUD A In the past 500 years, the study of anatomy has been an integral part of the training for two disciplines: the medical arts and the visual arts. The medical practitioner's knowledge of anatomy was and is an important means used to diagnose the patient's well-being or disorder and, if needed, could possibly lead to a course of treatment, especially if surgery might be called for. The classic representationist painter or sculptor's knowledge of anatomy enhanced the depiction of the human body. For some artists this was done so that evidence of the divine was made manifest. For other, later artists, especially those who were inspired by the principles of the Enlightenment, anatomy was thought to be a means to discover and portray the very nature of humanity. Traditionally, the medical practitioner’s and the artist's expertise in anatomy was often achieved through the cutting and probing of the cold cadaver; and, in one manner or another, recording one's observations. It was, and arguably still is, a critical way to satisfy and develop the so-called cool intellectual character of human curiosity―a means to speculate about nature, in this case human nature. But like so much of human curiosity it should be firmly rooted in human responsibility. It is not by chance that much of the profound and compassionate human expression in the visual arts and the medical arts has benefited from the impassionate analysis of the human body. (How or why did artists―or others―believe they could learn about the Divine through an exploration of the human body? Oddly, some religious traditions have forbidden depicting the human face or form. Until relatively recently, the ability to draw was deemed a valuable tool of the medical student. ―SJP) Steven J. Peitzman: “Praying Skeletons, Glorious Nudes: A Cultural History of Anatomical Art” Tuesday, September 30, 2014 in AUD A Is anatomical illustration an aid to learning the subject, a substitute for dissection, or in fact the end-product of anatomical exploration? Clearly the best of anatomical illustration is art—and the term more recently used is, in fact, “anatomical art.” Recently I’ve become entranced with the anatomical illustrations of old, and have come to understand that they can only be understood in the context of art and religion, as well as medicine. So, I’ll try to show how this is so, and also introduce a new theme— dissection to uncover disease. We will see skeletons praying, weeping, and also nudes mostly standing in one place. And what is that rhinoceros doing there? Florence Gelo: “Religious and Spiritual Aspects of the Dead” Friday, October 3, 2014 in AUD A The physical body has always been a mystery, a source of curiosity and a testimonial to the existence of God. Control of the body is a major concern for religion. Religion dictates morality (what is right and what is wrong) and acknowledges the human body itself as the vehicle to make visible the beliefs that religion holds about God and humanity. For example, religions have laws that extend through one's life time proscribing behavior, i.e. diet and sexual conduct. Religion dictates the proper care and disposal of the human body. For most religions dissection of the human body is of significant interest. For some, dissection is a violation of the sanctity of life. For other religions, dissection is permitted to advance knowledge of disease. If such knowledge can ultimately bring relief from illness and suffering, dissection is an act of love and autonomy is honored. Autonomy is a principle that informs more liberal religions for which body integrity after death is not strictly mandated. This lecture will explore historical and recent attitudes of the major religions to dissection and the disposal of human remains. (To what extent has dissection illustrated the “battle of science with religion”? Has such a battle really been a constant in Western history?- SJP) Steven J. Peitzman and Rhonda Soricelli: “Resurrectionists!” Friday, October 10, 2014 in AUD A Climbing grave yard fences at midnight. Digging up freshly buried corpses. Slinking through the streets with bodies in burlap sacks to sell them at the back doors of schools of anatomy. The activities of the Resurrectionists are classic materials of gothic horror stories but they also form an important part of the background of medical science and education, including in Philadelphia. Step back with us to a time when anatomy, plagued by a shortage of bodies, shook hands with the devil in its pursuit of cadavers for dissection and specimens of anatomical anomalies for museums. While the Resurrectionists were major suppliers of these materials, consider that you, as a student, and your professors might be called upon to make your own excursions to the grave yard to secure a corpse for tomorrow’s dissection at a time when BYOB meant “bring your own body.” Hopefully after learning about anatomical study in the time of the Resurrectionists you will have a greater appreciation for the bodies that greet you the next time you walk into the gross anatomy lab. Furthermore, you will see how the Resurrectionists have had an ongoing cultural impact on our understanding of medical science. This has been reflected in lurid fiction, films, and art up to the present day. (Particularly under the influence of the French philosopher Michel Foucault, many current historians focus on power relationships among groups and individuals. Who gets to determine what is “truth” and accepted practice? The question of who gets to dissect and who gets to be dissected until recently has exemplified power relationships in Western medicine. Why have body-snatching and related morbid activities--in fact, dissection itself--so strongly attracted the writer of fiction? Is there intended symbolism beyond the obvious sensational allure?--SJP) Anna Dhody: “Relevance of Anatomical Museums in the 21st Century” Friday, October 17, 2014 in AUD A The Műtter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia has become one of Philadelphia’s most popular destinations. Its vast collections of skulls, models, and anatomical and pathological specimens recall the sort of museum that at one time every sound medical school owned, for teaching and research. Anna Dhody, Curator of the Műtter Museum, will discuss how this arena of strange and sometimes ghastly materials still serves the needs of scientific investigation, while also stimulating the imaginations of artists, writers, historians, and curious Philadelphians and tourists. Another face of the Műtter uses museum artifacts and materials from the College of Physicians magnificent Historical Medical Library to tell the story of disease and medical progress. A current major show focuses on the Civil War: Broken Bodies, Suffering Spirits. Screening of the documentary Still Life: The Humanity of Anatomy (2002) by Thomas Cole, PhD (Session conducted by Dennis DePace and Rhonda Soricelli) Friday, October 24, 2014 in AUD A Are medical students and their cadavers at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) at Galveston any different from those at Drexel University College of Medicine? Has much changed in the Anatomy Lab in the past decade or so? Are there any “givens” for anyone, cadaver or student, in the Anatomy Lab? Surely participants at both ends of the scalpel wonder what the other will be like and would like to know his/her life story. Surely student dissectors take a huge leap into the unknown just as their cadaver donors have done in offering up their bodies for dissection. Come view this film (made at UTMB in 2002) that tells the unusual stories of two body donors while it also records the burial at sea of others. Listen to the reflections of a small group of students on their experience in the Anatomy Lab. After the film, join Drs. DePace and Soricelli in an informal conversation that will begin to set the stage for further discussions of both our shared and sometimes very unique responses to the act of cutting cold flesh. Rhonda Soricelli and guests, Austin Williams, MD, MSEd & Pam Hermann, MS: “Cadaver and Identity” Friday, October 31, 2014 in AUD A What’s in a name? While some students of anatomy never “name” their cadavers, others choose to do so. Why, and what leads to the choice of that name? In 2009, as freshmen med students at Drexel immersed in their own explorations of the human body in the anatomy lab, Austin Williams and Emily Greenwald embarked on a research project to explore the issues surrounding the naming of the cadaver. Using data from the survey instrument they developed that garnered over 1,100 responses from students at more than twelve different medical schools, Austin and Emily have just published their landmark paper, “Medical students’ reactions to anatomic dissection and the phenomenon of cadaver naming” in the journal Anatomical Sciences Education. Austin will share with you details of this project and its findings. Pam Hermann, a high school guidance counsellor, will join the conversation bringing her perspective as the daughter of a body donor, reflecting on her father’s choice to donate his body to science, his “anonymity” in the Anatomy Lab, and her life-affirming experience at the annual memorial service for donors’ families in Philadelphia. Rhonda Soricelli: “From the Lab to the Museum: Exploring the Experience of Dissection” Tuesday, November 4, 2014 in AUD A Contemporary society is fascinated by the anatomy of the human body. Elementary school students study rudimentary human anatomy in class; some U.S. high schools offer courses in dissection using human cadavers; our family and friends ask to be smuggled in to the anatomy lab after hours; anatomy games and puzzles abound on the internet; bloggers pontificate about the profound and the profane under the rubric of anatomy; and Vanessa Ruiz’s wonderful web site www.streetanatomy.com boasts of “obsessively covering the use of the human body in Medicine, Art and Design.” (Do check it out.) This overall movement has included renewed interest in the anatomical museum and in anatomical display. Philadelphia’s own world-famous Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians (www.collegeofphysicians.org) has experienced an annual increase in visitors from 5,000 to >120,000 in the past twenty-five years. Since 1995, the Body Worlds exhibits of Gunther von Hagens (www.bodyworlds.com) have been seen by over 38 million people worldwide and have spawned at least six copy-cat traveling shows. Body Worlds has been on exhibit twice at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, in October 2005 – April 2006 and in October 2009 – February 2010. A new incarnation, BODY WORLDS: PULSE is currently on view at Discovery Times Square in New York City through January 3, 2015. In this presentation which is intended as a “lead-in” to Dr. Fallon’s sessions, we will explore together how many medical students, mature physicians and artists before us have processed their responses to the experience of dissection through the visual and literary arts. We will also consider how the public responds to images of the dissected body and anatomical displays, and attempt to understand why that response may differ greatly from our own. (Do check out the Medical Humanities website for some provocative readings: poems, and excerpts from Body of Work: Meditations on Mortality from the Human Anatomy Lab by Christine Montross as you prepare your own reflection on your experience in the anatomy lab or in this course. Some reflections from previous Drexel students are also readily available on the Anatomy website. Remember that your submission of a thoughtful creative reflection earns one of the eight credits required for course completion. ―RLS.) Ted Fallon: “Creative and Affective Responses to Death and Dissection” Friday November 7, 2014 and Tuesday November 11, 2014 in SAC-A (Attendance at one of these sessions is mandatory for course completion. Students with surnames A – K should attend on November 7; those with surnames L – Z should attend on November 11. Contact Dr. Soricelli at RLSoricelli@comcast.net if you have a scheduling conflict. –RLS) Each of us endures the world essentially alone from within our own vessel. Each of us experiences the world through our own senses, and each of us chooses our own interpretations of the world. This is not to minimize the contributions that the world makes in offering us examples, opportunities for experience and traumas, and wisdom that others have garnered―especially at beginnings when we are supported and guided by others. But even from the beginning, we are also guided by our own affective responses that come from within. We alone experience our own horror, disgust, fear, love, warmth. As social beings, we strive to communicate these responses to others. We cannot help but experience a myriad of emotions as we see ourselves reflected in the corpse that lies before us. In this session, we will look at our own affective responses to dissection of the human body, and attempt to express the experience, first to ourselves and then to another. This exercise is important in itself in coming to terms with who we are as human beings and physicians working with the human body in all of its forms. It is also an exercise that can serve well as a model for helping us in all the difficult experiences we will have as human beings in the process of becoming physicians. Come, let your mind wander. Let us play with ideas, thoughts, feelings, words, images, sounds.