Boston Tea Party Story Board

advertisement

Boston Tea Party Storyboard

You will be creating a story board for the events of the Boston Tea Party by reading eyewitness accounts of the

event and selecting key information contained within them. A storyboard is a series of sketches, which show the

sequence of events for a movie script. They also work to establish time period, setting, point of view for cameras, props,

and costumes.

Creating Storyboards:

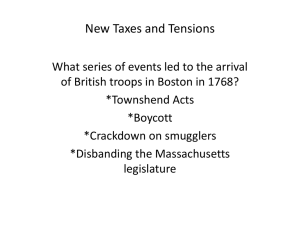

1) Read the eyewitness accounts and then ask yourself the following questions. How are the three accounts

similar and different? How do you know a witness is telling the truth? How can you find out?

Here are a few details to support your decision:

Consistencies: All witnesses describe a town meeting prior to the act; the eerie silence of the

spectators; the orderliness of the protestors; the lack of interference from the British Navy; the

strict adherence to not touching other goods or destroying the ships; the length of the event (which

was about 3 hours); the approximate number of participants (150 to 200); and the “Indian”

costumes of the protestors.

Participation: Hewes was disguised in the “costume of an Indian,” but Sessions was not, since his

participation was not planned. Andrews just watched. Hewes’s account is more complete and

detailed and told in the first person. He takes a starring role in procuring the hatch keys and

chastising Captain O’Conner.

Facts:

o About 150 men boarded three ships (Captain Hall’s Dartmouth, Captain Coffin’s Eleanor, and

Captain Bruce’s Beaver).

o The men axed to pieces 342 chests of tea and threw 10 tones of it into Boston Harbor.

o Soldiers had orders to protect the tea, but they just stood by and watched.

o The tea, worth almost 10,000 British Pounds, belonged to the East India Company. Thus,

the act was illegal.

2) The eyewitness accounts will provide the basis for the story, but you will need to find additional information

to help fill in the blanks. You will need to provide captions that help with the dialogue of the characters

pictured. You should select a series of six to ten events or scenes in order to ensure that you accurately

detail the event. You will be graded on accuracy, content, and the order and flow of the story.

Who were the Eyewitnesses?

John Andrews: was a selectman, a member of Boston’s governing board. He observed, but did not participate

in the Boston Tea Party. In a letter to his brother, he wrote that he feared the British would crack down on Boston for

destroying “ten thousand pounds sterling of the East India Company’s tea.”

Robert Sessions: hailed from Connecticut, but was living in Boston at the time. He joined the mob

spontaneously. In the letter to his family, he claimed he did it simply because there were not enough men to finish the

job quickly.

George Hewes: was an ordinary workingman, a cobbler, who found himself in extrodinary times and places in

history. He was at the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. In fact, he knew four of the five men killed. Later, Hewes

was a witness at the trial of Captain Preston, the British officer in charge of the troops during the massacre.

The Boston Tea Party became Hewes’s ultimate claim to fame. His shoe store was on Griffin’s Warf, the site of

the rebellion. Afterward, he retold his story of the Tea Party well into his 90’s, when he became famous as the oldest

living survivor of the Boston Tea Party. Though his story is generally considered reliable, his advanced age and celebrity

status clouded some of the facts.

1

Eyewitness Accounts:

Hewes:

On the day preceding the seventeenth, there was a meeting of the citizens of the county of Suffolk,

convened at one of the churches in Boston, for the purpose of consulting on what measures might be

considered expedient to prevent the landing of the tea, or secure the people from the collection of the duty. At

that meeting a committee was appointed to wait on Governor Hutchinson, and request him to inform them

whether he would take any measures to satisfy the people on the object of the meeting.

To the first application of this committee, the Governor told them he would give them a definite answer

by five o'clock in the afternoon. At the hour appointed, the committee again repaired to the Governor's house,

and on inquiry found he had gone to his country seat at Milton, a distance of about six miles. When the

committee returned and informed the meeting of the absence of the Governor, there was a confused murmur

among the members, and the meeting was immediately dissolved, many of them crying out, "Let every man do

his duty, and be true to his country"; and there was a general huzza for Griffin's wharf.

It was now evening, and I immediately dressed myself in the costume of an Indian, equipped with a

small hatchet, which I and my associates denominated the tomahawk, with which, and a club, after having

painted my face and hands with coal dust in the shop of a blacksmith, I repaired to Griffin's wharf, where the

ships lay that contained the tea. When I first appeared in the street after being thus disguised, I fell in with many

who were dressed, equipped and painted as I was, and who fell in with me and marched in order to the place of

our destination.

Andrews:

They mustered, I’m told, upon Fort Hill, to the number of about two hundred, and proceeded, two by

two, to Griffin’s Warf, where Hall, Bruce, and Coffin {the British captains} lay . . . {Coffin’s ship} was freighted

with a large quantity of other goods, which they took the greatest care not to injure in the least.

Sessions:

I went immediately to the spot. Everything was a light as day by the means of lamps and torches – a pin

might be seen lying on the wharf. I went on board where they were at work and took hold with my own hands.

Andrews:

They say the actors were Indians from Narragansett. Whether they were or not . . . they appeared as

such, being clothed in blankets with the heads muffled, and copper-colored skin, being each armed with a

hatchet or ax, and pistols.

Sessions:

I was a volunteer, the disguised men being largely men of family and position in Boston, while I was a

young man from Connecticut. The appointed and disguised party proving too small for the quick work

necessary, other young men, similarly circumstanced with myself, joined them in their labors.

Hewes:

When we arrived at the wharf, there were three of our number who assumed an authority to direct our

operations, to which we readily submitted. They divided us into three parties, for the purpose of boarding the

three ships . . . at the same time . . . the commander ordered me to go to the captain and demand of him the

keys to the hatches and a dozen candles. . . . The captain promptly . . . delivered the articles, but requested me

at the same time to do no damage to the ship or rigging.

Sessions:

The chests were drawn up by a tackle, on ebringin them forward in the hold, another putting a rope

around them, and others hoisting them to the deck and carrying them to the vessel’s side. The chests were then

opened, the tea emptied over the side and the chests thrown overboard.

Hewes:

We then were ordered by our commander to open the hatches and take out all the chests of tea and

throw them overboard. . . . We immediately proceeded to execute his orders, first cutting and splitting the

chests with our tomahawks, . . . to expose them to the effects of the water. In about three hours . . . we had

thus broken and thrown overboard every tea chest to be found in the ship. . . . We were surrounded by British

armed ships, but no attempt was made to resist us.

2

Sessions:

Although there were many people on the wharf, entire silence prevailed – no clamor, no talking.

Nothing was meddled with, but the teas on board. After having emptied the hold, the deck was swept clean,

and everything was put in its proper place. An officer on board was requested to come up from the cabin and

see that no damage was done except to the tea.

Hewes:

There were several attempts . . . to carry off small quantities of tea. . . . One Captain O’Conner, whom I

well knew, came on board for that purpose. . . . When he supposed he was not noticed, he filled his pockets,

and also the lining of his coat. But I had detected him and informed the captain. . . . We were ordered to take

him into custody. . . . Just as he was stepping from the vessel, I seized him by the skirt of his coat, and in an

attempt to pull him back, I tore it off; but, springing forward, by a rapid effort, he made his escape. He had,

however, to run a gauntlet through the crowd . . . each one, as he passed, giving him a kick or stroke.

Andrews:

Not the least insult was offered to any person, save one Captain Conner . . . who had ripped up the lining

of his coat . . . and nearly filled it with tea, but being detected, was handled pretty roughly. They not only

stripped him of his clothes, but gave him a coat of mud, with a severe bruising into the bargain.

Hewes:

Another attempt was made to save a little tea . . . by a tall, aged man, who wore a large cocked hat and

white wig, which was fashionable at the time. He had . . . slipped a little into his pocket, but being detected,

they seized him and, taking his hat and wig from his head, threw them, together with the pocketed tea . . . into

the water. In consideration of his advanced age, he was permitted to escape, with now and then a slight kick.

3