Mirages

advertisement

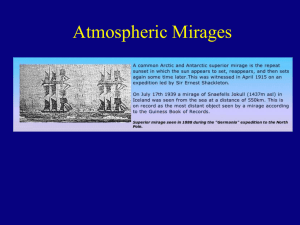

Karina Khristich SCI 111a Mirages A mirage is an optical phenomenon that creates the illusion of water and results from the refraction of light through a non-uniform medium. Mirages are most commonly observed on sunny days when driving down a roadway. As you drive down the roadway, there appears to be a puddle of water on the road several yards (maybe one-hundred yards) in front of the car. Of course, when you arrive at the perceived location of the puddle, you recognize that the puddle is not there. Instead, the puddle of water appears to be another one-hundred yards in front of you. You could carefully match the perceived location of the water to a roadside object; but when you arrive at that object, the puddle of water is still not on the roadway. The appearance of the water is simply an illusion. The illusion results from the way in which light is refracted (bent) through air at different temperatures. Cold air has a higher index of refraction than hot air does. This is due to the fact that cold air is more dense than hot air and light travels slower through it. If light travels through constant temperature then it will travel in a straight line. As light travels at a shallow angle along a boundary between airs of different temperature, the light rays bend towards the colder air. If the air near the ground is warmer than that higher up, the light ray bends upward, effectively being totally reflected just above the ground. But our brain thinks the light has travelled in a straight line. It doesn't see the image as bent light from the sky. Instead, our brain thinks the light must have come from something on the ground. There are two categories of two-image (classical) mirages: inferior and superior. 1. Inferior mirage For exhausted travelers in the desert, an inferior mirage may appear to be a lake of water in the distance. An inferior mirage is called "inferior" because the mirage is located under the real object. The real object in an inferior mirage is the (blue) sky or any distant (therefore bluish) object in that same direction. The mirage causes the observer to see a bright and bluish patch on the ground in the distance. Light rays coming from a particular distant object all travel through nearly the same air layers and all are bent over about the same amount. Therefore, rays coming from the top of the object will arrive lower than those from the bottom. The image usually is upside down, enhancing the illusion that the sky image seen in the distance is really a water or oil puddle acting as a mirror. Inferior images are not stable. Hot air rises, and cooler air (being more dense) descends, so the layers will mix, giving rise to turbulence. The image will be distorted accordingly. It may be vibrating; it may be vertically extended (towering) or horizontally extended (stooping). If there are several temperature layers, several mirages may mix, perhaps causing double images. In any case, mirages are usually not larger than about half a degree high (same apparent size as the sun and moon) and from objects only a few kilometers away. Heat haze Heat haze, also called heat shimmer, refers to the inferior mirage experienced when viewing objects through a layer of heated air. On tarmac roads it may look as if water, or even oil, has been spilled. These kinds of inferior mirages are often called "desert mirages" or "highway mirages". Convection causes the temperature of the air to vary, and the variation between the hot air at the surface of the road and the denser cool air above it creates a gradient in the refractive index of the air. This produces a blurred shimmering effect, which affects the ability to resolve objects. Light from the sky at a shallow angle to the road is refracted by the index gradient, making it appear as if the sky is reflected by the road's surface. The mind interprets this as a pool of water on the road, since water also reflects the sky. The illusion fades as one gets closer. 2. Superior mirage A superior mirage occurs when the air below the line of sight is colder than the air above it. This unusual arrangement is called a temperature inversion, since warm air above cold air is the opposite of the normal temperature gradient of the atmosphere. Passing through the temperature inversion, the light rays are bent down, and so the image appears above the true object, hence the name superior. Superior mirages are in general less common than inferior mirages, but, when they do occur, they tend to be more stable, as cold air has no tendency to move up and warm air has no tendency to move down. A superior mirage can be right-side up or upside down, depending on the distance of the true object and the temperature gradient. Often the image appears as a distorted mixture of up and down parts. Superior mirages are quite common in polar regions, especially over large sheets of ice that have a uniform low temperature. Superior mirages also occur at more moderate latitudes, although in those cases they are weaker and tend to be less smooth and stable. For example, a distant shoreline may appear to tower and look higher (and, thus, perhaps closer) than it really is. Superior mirages can have a striking effect due to the Earth's curvature. Were the Earth flat, light rays that bend down would soon hit the ground and only nearby objects would be affected. Since Earth is round, if their downward bending curve is about the same as the curvature of the Earth, light rays can travel large distances, perhaps from beyond the horizon. In the same way, ships that are in reality so far away that they should not be visible above the geometric horizon may appear on the horizon or even above the horizon as superior mirages. This may explain some stories about flying ships or coastal cities in the sky, as described by some polar explorers. These are examples of so-called Arctic mirages. 2.1 Fata Morgana A Fata Morgana is a very complex superior mirage. It appears with alternations of compressed and stretched zones, erect images, and inverted images. A Fata Morgana is also a fast-changing mirage. Fata Morgana mirages are most common in polar regions, especially over large sheets of ice with a uniform low temperature, but they can be observed almost anywhere. For a Fata Morgana, temperature inversion has to be strong enough that light rays' curvatures within the inversion are stronger than the curvature of the Earth. The rays will bend and create arcs. An observer needs to be within an atmospheric duct to be able to see a Fata Morgana. Fata Morgana mirages may be observed from any altitude within the Earth's atmosphere, including from mountaintops or airplanes. A Fata Morgana can go from superior to inferior mirage and back within a few seconds, depending on the constantly changing conditions of the atmosphere. Sixteen frames of the mirage of the Farallon Islands, which cannot be seen from sea level at all under normal conditions because they are located below the horizon, were photographed on the same day. The first fourteen frames have elements of a Fata Morgana display—alternations of compressed and stretched zones. The last two frames were photographed a few hours later around sunset. The air was cooler while the ocean was probably a little bit warmer, which made temperature inversion lower. The mirage was still present, but it was not as complex as it had been a few hours before sunset, and it corresponded no longer to a Fata Morgana but rather to a superior mirage display. A mirage is an optical phenomenon that creates the illusion of water and results from the refraction of light through a non-uniform medium. Mirages are most commonly observed on sunny days when driving down a roadway. As you drive down the roadway, there appears to be a puddle of water on the road several yards (maybe one-hundred yards) in front of the car. Of course, when you arrive at the perceived location of the puddle, you recognize that the puddle is not there. Instead, the puddle of water appears to be another one-hundred yards in front of you. You could carefully match the perceived location of the water to a roadside object; but when you arrive at that object, the puddle of water is still not on the roadway. The appearance of the water is simply an illusion. The illusion results from the way in which light is refracted (bent) through air at different temperatures. Cold air has a higher index of refraction than hot air does. This is due to the fact that cold air is more dense than hot air and light travels slower through it. If light travels through constant temperature then it will travel in a straight line. As light travels at a shallow angle along a boundary between airs of different temperature, the light rays bend towards the colder air. If the air near the ground is warmer than that higher up, the light ray bends upward, effectively being totally reflected just above the ground. But our brain thinks the light has travelled in a straight line. It doesn't see the image as bent light from the sky. Instead, our brain thinks the light must have come from something on the ground. There are two categories of two-image (classical) mirages: inferior and superior. 1. Inferior mirage For exhausted travelers in the desert, an inferior mirage may appear to be a lake of water in the distance. An inferior mirage is called "inferior" because the mirage is located under the real object. The real object in an inferior mirage is the (blue) sky or any distant (therefore bluish) object in that same direction. The mirage causes the observer to see a bright and bluish patch on the ground in the distance. Light rays coming from a particular distant object all travel through nearly the same air layers and all are bent over about the same amount. Therefore, rays coming from the top of the object will arrive lower than those from the bottom. The image usually is upside down, enhancing the illusion that the sky image seen in the distance is really a water or oil puddle acting as a mirror. Inferior images are not stable. Hot air rises, and cooler air (being more dense) descends, so the layers will mix, giving rise to turbulence. The image will be distorted accordingly. It may be vibrating; it may be vertically extended (towering) or horizontally extended (stooping). If there are several temperature layers, several mirages may mix, perhaps causing double images. In any case, mirages are usually not larger than about half a degree high (same apparent size as the sun and moon) and from objects only a few kilometers away. Heat haze Heat haze, also called heat shimmer, refers to the inferior mirage experienced when viewing objects through a layer of heated air. On tarmac roads it may look as if water, or even oil, has been spilled. These kinds of inferior mirages are often called "desert mirages" or "highway mirages". Convection causes the temperature of the air to vary, and the variation between the hot air at the surface of the road and the denser cool air above it creates a gradient in the refractive index of the air. This produces a blurred shimmering effect, which affects the ability to resolve objects. Light from the sky at a shallow angle to the road is refracted by the index gradient, making it appear as if the sky is reflected by the road's surface. The mind interprets this as a pool of water on the road, since water also reflects the sky. The illusion fades as one gets closer. 2. Superior mirage A superior mirage occurs when the air below the line of sight is colder than the air above it. This unusual arrangement is called a temperature inversion, since warm air above cold air is the opposite of the normal temperature gradient of the atmosphere. Passing through the temperature inversion, the light rays are bent down, and so the image appears above the true object, hence the name superior. Superior mirages are in general less common than inferior mirages, but, when they do occur, they tend to be more stable, as cold air has no tendency to move up and warm air has no tendency to move down. A superior mirage can be right-side up or upside down, depending on the distance of the true object and the temperature gradient. Often the image appears as a distorted mixture of up and down parts. Superior mirages are quite common in polar regions, especially over large sheets of ice that have a uniform low temperature. Superior mirages also occur at more moderate latitudes, although in those cases they are weaker and tend to be less smooth and stable. For example, a distant shoreline may appear to tower and look higher (and, thus, perhaps closer) than it really is. Fata Morgana A Fata Morgana is a very complex superior mirage. It appears with alternations of compressed and stretched zones, erect images, and inverted images. A Fata Morgana is also a fast-changing mirage. Fata Morgana mirages are most common in polar regions, especially over large sheets of ice with a uniform low temperature, but they can be observed almost anywhere. For a Fata Morgana, temperature inversion has to be strong enough that light rays' curvatures within the inversion are stronger than the curvature of the Earth. The rays will bend and create arcs. An observer needs to be within an atmospheric duct to be able to see a Fata Morgana. Fata Morgana mirages may be observed from any altitude within the Earth's atmosphere, including from mountaintops or airplanes. A Fata Morgana can go from superior to inferior mirage and back within a few seconds, depending on the constantly changing conditions of the atmosphere. 3. Three-image mirages When an inverted image lies between two erect ones, it is called a three-image mirage. The top image is often strongly compressed. These purely refractive phenomena are also caused by inversion layers. They are of at least two kinds: 3.1 The “mock mirage” Caused by looking down into an inversion below eye level, and then (thanks to the curvature of the Earth) out through it again beyond the horizon. The miraged objects may be about the same height above sea level as the eye, or may be considerably higher. 3.2 Wegener's “late mirage” Caused by looking up through an inversion above the observer. The miraged objects are always higher than eye level (e.g., distant mountains; astronomical objects). A true superior mirage of objects below the inversion may also be present, if the inversion is strong enough. 4. Mirages of higher multiplicity. There are also distinct 5-image mirages. These have not been analyzed; they are certainly associated with strong thermal inversions, but the optical details are obscure. Night-time mirages The conditions for producing a mirage can take place at night. Under most conditions, these are not observed. Mirage of astronomical objects A mirage of an astronomical object is a naturally occurring optical phenomenon, in which light rays are bent to produce distorted or multiple images of an astronomical object. The mirages might be observed for such astronomical objects as the Sun, the Moon, the planets, bright stars, and very bright comets. The most commonly observed are sunset and sunrise mirages. 1. Three-image mirages When an inverted image lies between two erect ones, it is called a three-image mirage. The top image is often strongly compressed. These purely refractive phenomena are also caused by inversion layers. They are of at least two kinds: 1.1 The “mock mirage” Caused by looking down into an inversion below eye level, and then (thanks to the curvature of the Earth) out through it again beyond the horizon. The miraged objects may be about the same height above sea level as the eye, or may be considerably higher. 1.2 Wegener's “late mirage” Caused by looking up through an inversion above the observer. The miraged objects are always higher than eye level (e.g., distant mountains; astronomical objects). A true superior mirage of objects below the inversion may also be present, if the inversion is strong enough. 2. Mirages of higher multiplicity There are also distinct 5-image mirages. These have not been analyzed; they are certainly associated with strong thermal inversions, but the optical details are obscure. Night-time mirages The conditions for producing a mirage can take place at night. Under most conditions, these are not observed. However, under some circumstances lights from moving vehicles, aircraft, ships, buildings, etc. can be observed at night, even though, as with a daytime mirage, they would not be observable. Mirage of astronomical objects A mirage of an astronomical object is a naturally occurring optical phenomenon, in which light rays are bent to produce distorted or multiple images of an astronomical object. The mirages might be observed for such astronomical objects as the Sun, the Moon, the planets, bright stars, and very bright comets. The most commonly observed are sunset and sunrise mirages.