Section for Court Interpreters of the Association of

advertisement

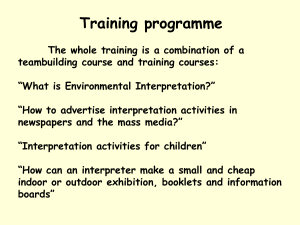

Section for Court Interpreters of the Association of Scientific and Technical Translators of Slovenia Abstract The article outlines the work of the Section for Court Interpreters of the Association of Scientific and Technical Translators of Slovenia (in Slovenian: Sekcija sodnih tolmačev Društva znanstvenih in tehniških prevajalcev Slovenije, abbreviated as: SST DZTPS), which was established in response to the adoption of the Directive 2012/64/EU on the right to interpretation and translation in criminal proceedings. First it gives a general overview of the Association, which is followed by the mission and activities of the Section for Court Interpreters. The legislative framework with the role of the regulator is also presented, emphasizing its role as the entity responsible for organising the certification test and maintaining the national register of court interpreters. Furthermore, the CPD program of the Section and its future challenges are outlined. Instead of the conclusion, the joys and sorrows of life as a translator and interpreter are discussed. Key words: Section for Court Interpreters of DZTPS, the regulator, certification test, the national register of court interpreters, CPD program, public procurement Section des traducteurs et interprètes juridiques de l'Association slovène des traducteurs scientifiques et techniques Barbara Rovan chairs the Section for Court interpreters of DZTPS. She is a freelance translator and interpreter for English, Japanese and Slovenian, based in Ljubljana, Slovenia. She is a court interpreter for the English /Slovenian language combination and holds a PhD in Applied Linguistics. 1. The Association of Scientific and Technical Translators of Slovenia The Association of Scientific and Technical Translators of Slovenia, abbreviated in Slovenian as DZTPS (an acronym standing for Društvoznanstvenih in tehniškihprevajalcevSlovenije), was established in 1960 in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. Court interpreters were among its founding members. Currently the Association has approximately 450 members. The majority hold a university degree in languages, while one third studied other subjects (see: Graph 1). University graduates of 33% languages 67% other Graph 1: Study programmes of DZTPS members, 2007 According to data for 2013, their main fields of translation are the following: Fields of Translation economics elec. engineering construction 2% 13% humanities 17% 7% IT 6% 6% chemistry/biology agriculture/forestry mgmt 18% 16% 6% medicine/pharm. politics 3% 3% law 1% mechanical engineering 2% tourism other Graph 2: Main fields of translation, 2013 Languages of Translation 3% English 1% French 2% 7% 9% German 36% 8% 2% Bosnian Croatian 23% 9% Serbian Italian Spanish Russian Hungarian Graph 3: Main languages of translation (more than 10 translators), 2013 In addition to English, the lingua franca of modern times, the majority of members work from and into German, Croatian, Serbian and Bosnian, Italian, French and Hungarian, which are the languages of countries with which Slovenia has had traditionally strong links. (See: Graph 3). All members of the Association accept the Code of Conduct that is modelled onthe Translator’s Charter of FIT. DZTPS has been the member of FIT since 1993. 2. The Section for Court Interpreters The members of the Section for Court Interpreters of DZTPS are those members of the Association who are accredited court interpreters and accept the Code of Ethics of the Section which is in line with the Code of Ethics of EULITA. The Section was established in December 2011 in direct response to the TRAFUT workshop organized in November 2011 in Ljubljana by EULITAin order to disseminate information about the transposition of the Directive 2010/64/EU on the right to interpretation and translation in criminal proceedingsto the national law of EU member states. On the basis of the information gathered at the workshop, court interpreters in the Association established that there was a need to be better organised. It was decided that a Section within DZTPS would be the right form of organisation, because of a long tradition of court interpreters’ membership in DZTPS and because of the belief that it would provide a good environment for the work of the Section. The mission of the Section for Court Interpreters of DZTPS is to carry out its activities in order to promote the quality of justice and to ensure the access to justice to participants in court and in administrative proceedings in Slovenia who do not speak the Slovenian language. The Section operates in accordance with the Statutes of its parent association DZTPS. The General Assembly of Section members is the highest authority, which adopts basic statutory documents and elects the Section’s Executive Committee. Since May 2012 the Section for Court Interpreters of DZTPS has been a full member of EULITA, the only organisation from Slovenia having such a status. Regular activities of the Section include promoting the interest of its members on legal interpreting and translation matters vis-à-vis the Ministry of Justice, the judiciary and other interested parties, organising Continuous Professional Development courses, promoting quality in legal interpreting and translation through the promotion of the professional status of legal interpreters and translators, representing its members as a full member of EULITA, disseminating information regarding issues of concern to legal interpreters and translators, participating in EU projects, promoting close cooperation with academic institutions in the field of training and research, and organising events on issues such as training, research, etc. 2.1 The legal framework There are two key pieces of legislation governing the work of court interpreters in Slovenia, a law and a by-law. The law is theCourts Act1which in Articles 84 stipulates: “Court interpreters are persons appointed for an unlimited period of time with the right and duty to, upon the court’s request, interpret in hearings or translate documents.”The Act treats court interpreters on equal terms with expert witnesses and court appraisers as persons with a special status of public confidence conferred upon them by the Ministry of Justice.The by-law is entitled the Rules on Court Interpreters2and governs in detail the manner of appointment and dismissal of court interpreters; the certification test;the manner in which court interpreters have to conduct their work; the rate and reimbursement of expenses etc. The Rules on Court Interpreters were amended in January 2012 to provide for the transposition of the Directive 2010/64/EU. Article 29a of the Rules definesthe submissionof evidence of continuous professional development (hereinafter: CPD) by stipulating that a court interpreter shall for each individual language take part in at least five CPD seminars in the period stipulated by the Act. The first assessment period of certificates submitted to the Ministry of Justice shall continue until the end of 2016. 2.2 The regulator In accordance with Slovenian legislation The Ministry of Justice (hereinafter: the MOJ) is the regulator responsible for the appointment and dismissal of court interpreters, the certification test and the register of court interpreters. Court interpreters are appointed by the Minister of Justice following a general administrative procedure as provided in the Rules on Court Interpreters in compliance with the Courts Act. Based on a candidate’s suitability, the Minister issues a decision on a candidate’s appointment or refusal as a court interpreter, with the operative part of the decision stating the (foreign) language for which he/she has been appointed or refused as court interpreter. The act of appointment of a court interpreter is published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, with the name of the relevant court interpreter entered thereupon into the National Register of Certified Court Interpreters administered by the MOJ.Court interpreters are appointed for anunlimited period of time. Published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of SloveniaUradni list Republike Slovenije, št. 19/1994. Published in the Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia Uradni list RepublikeSlovenije,št. 88/2010, amended in nos. 1/2012, 35/2013. 1 2 2.2.1 Certification test The MOJ Judicial Training Centre organises general and specialised orientation training seminars focused on the preparation of candidates for special certification tests. General seminars arethe samefor all court interpreter candidates irrespective of the declared language, while specialised seminars are aimed at acquiring professional domain expertise in individual languages. As of September 2013, the attendance fee for an orientation training seminar is EUR 427,73. The certification test includes proficiency testing of the language for which the candidate wishes to become licensed as a court interpreter, and of the candidate’s legal knowledge base, namely related to: basic institutions of the constitutional arrangement of the Republic of Slovenia; organisation and administration of justice and judiciary; basic knowledge of court procedures which are the most common type of interpreting assignment for court interpreters; legal provisions related tothe rights and duties of a court interpreter; law and institutions of the European Union; formatting and certification of translations as well as recordkeeping of assignments. The court interpreter certification test includes a written and oral proficiency examination. The test is run by an examination board composed of 4 members – chair, recording clerk and 2 members. Members of the examination board are appointed, as a rule, from academic foreign language teaching staff and from among court interpreters with at least five years’ experience in court interpreting – the latter being often appointed from the DZTPS membership, and from among members of the Association for the deaf (for sign language candidates), and occasionally, as and when required, also other persons with good proficiency in a declared foreign language, and aMOJ officer with a graduate degree in law conferred upon in the Republic of Slovenia or an equivalent degree according to the law. Candidates are allowed approximately four hours at the most to complete the written examination in which they have to prove their proficiency in translating legal documents such as charges, contracts, certificates, bills of indictment, court rulings, from source into the target language and vice versa of the declared bilingual combination. After the written tests are marked, the oral examination takes place, lasting for about an hour during which the candidate's knowledge of basic institutions of constitutional arrangement, penal and civil law proceedings, as well as organisation of judicial and administrative authorities, is tested, on the one hand, and his/her ability to successfully render meaning from the source language to the target language while interpreting in the consecutive mode and while sight translating legal documents, on the other hand. If the candidate passes the court interpreter’s certification test, he/she is eligible to take the oath and be appointed court interpreter by the Minister of Justice. The candidate having failed the written examination may sit the examination again within a period of time to be agreed upon by the examination board, but not earlier than six months and not later than two years after the date of failure.Any candidate who fails the oral examination must re-sit the entire test again.The entire certification test may be repeated up to three times. As of September 2013 the cost of the certification test is priced at EUR 275,71. The court interpreter starts to perform his duties after having taken the oath and after having been served the relevant decision and certificate of appointment, including the court interpreter’s record book of assignments. The court interpreter also receives an ID-card and his official seal or stamp, to be provided by the MOJat the court interpreter’s expense. The results of the certification tests conducted in 2012 show that approximately one fifth of the candidates managed to pass the test. No. of candidates 58 passed 11 failed 38 cancelled applications 9 pass rate 18.97% Table 1: Results of the certification tests in 2012, Source: MOJ Judicial Training Centre 2.2.2 The national register of court interpreters The MOJ is responsible also for maintaining the national register of court interpreters. According to its data, as of 16 September 2013,there were 683 court interpreters on the register. However, the MOJ has been responsible for the register only since 1994, when the current Courts Act3 entered into force, while prior to that registers were maintained by the courts. Several court interpreters who were entered on the register in the period prior to 1994 may currently not be active anymore. Only at the end of 2016, when the deadline for submitting CPD certificates expires, the number of active court interpreters in Slovenia will become known. 2.3 The Continuous Professional Development Program of the Section The CPD program of the Section was launched in March 2012. Up until September 2013 we have organised 11 seminars attended in total by more than 600 participants. The program comprises three modules that were identified as core topics on the basis of the results of a questionnaire survey conducted among the court interpreters registered in Slovenia prior to the launch of the program. The three modules cover the following topics: General Module - fields of law (criminal law, civil law, corporate law, administrative law etc.) A thorough approach is taken with seminars organised separately for procedural law and substantive law issues. The Courts Act (Uradni list RepublikeSlovenije, št. 19/1994) in the second paragraph of Article 88 stipulates that the national register of expert witnesses is maintained by the MOJ, while Article 92 stipulates that the provision applies also to court appraisers and court interpreters. 3 - users of court interpreting services (judges, police staff, attorneys-at-law, prosecutors, notaries etc.) Feedback from the users of our services is very important because it helps us to improve. - researchers of legal language In order to gain a better insight into the linguistic research, prominent linguists are invited to discuss selected topics. Language module Seminars in the language module fall into two categories, one for languages such as English, German, French, Italian, Serbian, Croatian, for which there are many lecturers and many participants, and the other for languages such as Dutch, Chinese, Albanian, Arabic, Rumanian, for which there are few lecturers and few participants. For the first category it is not difficult to organise good seminars, while for the second one it is rather difficult. For court interpreters accredited for the latter category the Section has decided to organise workshops on the translation of legal cautions, and to provide the information to its members about CPD webinars organised for court interpreters by other EULITA and FIT members. Interpreting techniques module This module is yet to be launched, the plan is to organise it in cooperation with the University of Ljubljana and the University of Maribor. All seminars are evaluated by the participants. Attention is paid to organising seminars not only in the capital, Ljubljana, but also in Maribor and Koper. 2.4 The future challenges of the Section In addition to continuing the CPD program, the Section shall focus on: strengthening contacts with the regulator and the judiciary Issues to be discussed include the submission of proposals for legislation amendments, gradual introduction of the e-signature, the opportunity for prior study of the case-files etc. dissemination of information to the general public regarding the work of court interpreters, the transposition of Directive 2010/64/EU etc. inclusion of the Article on the Section in the Statutes of DZTPS assistance in the revitalization of DZTPS 3. The life of interpreters and translators - joy and sorrow? Instead of a conclusion I would like to attempt to answer the question posed in the title of the 11th International Forumorganized by the FIT Committee for Legal Translation and Court Interpreting in cooperation with the Association of Scientific and Technical Translators of Serbia. The answers to the question, where is the joy and where is the sorrow, are not given just from the position of a court interpreter but of a translator and interpreter in general. JOY job well done Knowing that we have assisted somebody in communicating, often in difficult circumstances, leads to job satisfaction. SORROW late payments In Slovenia late payments are not unusual and quite often one has to wait for half a year or more to receive payment for translation and interpreting assignments. indirect and direct consequences of EU public procurement procedures pursuant to regulations originally not designed for intellectual services As translators and interpreters we have all witnessed in the recent decades immense transformation of our market, partly caused by advances in technology and partly by an approach to the public procurement of translation and interpreting services. The sorrow to which I would like to draw your attention at the very end of my presentation at this forum is the latter issue, which seems to stem from the fact that in the EU all public procurement is conducted in accordance with financial regulations (currently New Financial Regulation No. 966/2012 of 25/10/2012 of the financial rules applicable to the general budget of the EU repealing Council Regulation No. 1605/2002) that were originally not designed for intellectual services. The Financial Regulation was originally designed for the procurement of infrastructural projects, and it is understandable that if one is to commission the construction of a tunnel,for example, it is preferable that the job is given to just one company. In such a case the cascading principle in accordance to which the job is always first offered to the first successful contractor on the list is understandable, however, in the case of intellectual services such as translation and interpreting, it makes no sense, because of multiple assignments covered by one public tender which could be carried out by many contractors. Although the original financial regulation was amended on several occasions, its concept remains the same and has caused severe market distortions in the procurement of translation and interpreting services at the EU level and at the national level of Member States where the same regulation applies as transposed into their respective legislations, and even in countries that have only an Association Agreement signed with the EU and already think that copying EU procurement legislation is a good thing. At all these levels we have witnessed how the application of the cascading principle causes market distortions by adding many intermediaries in the long chain between the one commissioning a translation service and the actual translator of the document (at the level of the EU administration, national administrations and agencies). Very often, the bubbles are being created artificially in the form of big agencies, which eventually end up bursting, because they cannot provide good quality services over a sustained period of time. In my opinion research should be done at the international and national level into the impact of EU procurement procedures on the translation and interpreting services with the view to whether the implementation of these rules in practice leads to a distortion in the translation and interpreting market that could be measured in social and economic costs, both at the level of the individual and society. Furthermore, the impact on the quality of these services should be assessed. Indicators such as the cost of educating a translator or an interpreter, and the losses to the pensions insurance fund, health insurance fund and tax collection because they are not working or have to work for agencies without paying taxes and other contributions should be taken into account from the macroeconomic perspective. Or else, a case study could be made to analyse the structure of the cost of translation that was selected by a public procurement procedure, i.e. price per page, the share paid to the person translating, the share paid to the intermediary, the share of taxes and social contributions paid. The result of the research should then be presented to the decision makers and hopefully they will share our sorrow over the situation and agree that intellectual services should be procured in a completely different manner that is currently the case. With fewerincompetent intermediaries, paid for dearly by taxpayers, the translation market could provide better results.