View/Open - Sacramento

advertisement

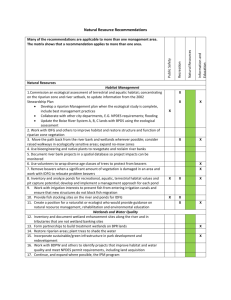

4 Chapter 2 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING The study area is located in the lower Sacramento Valley of central California (Figure 1), a geographical expanse roughly coinciding with present day Sacramento County. It is bordered on the north by the American River and on the south by the Mokelumne River. The eastern boundary is the Sierra Nevada foothills and the western boundary is defined by the western bank of the Sacramento River. The study area is approximately 1258.6 square kilometers (311,000 acres) in size. Geographically, the lower Sacramento Valley can be characterized as a low-elevation “flatland” composed of alluvial plains, river channels, sloughs, wetlands, and uplands of low relief (Moratto 1984:168). Elevations in the study area range from sea level in the Delta to around 500 feet (152 meters) in the foothills (ARNHA 2004:1). The lower Sacramento Valley possesses a Mediterranean climate characterized by mild winters and warm dry summers (ARNHA 2004:11). The rainy season generally occurs from November to March when approximately 75 percent of the annual 17.5 inches of precipitation is received (ARNHA 2004:11; City of Sacramento 2010). Tule fog, a type of radiation fog, is also common during winter months, when moisture condenses as warm air from the earth meets cool air draining into the valley from the foothills and mountains. Winter lows range between -7.2 and -4.4 degrees Celsius (19 and 24 degrees Fahrenheit), but average 3.3 degrees Celsius (38 degrees Fahrenheit) (City of Sacramento 2010). Summer temperatures can exceed 37.8 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit) but are accompanied by extremely low (≤ 20 percent) relative humidity and typically rapid evening cooling as cold marine air invades the area toward sunset. Three vegetation communities are found within the study area: freshwater marsh, grassland, and riparian woodland. The freshwater marsh comprises about 437.74 square kilometers (108,168 acres), the grassland 147.62 square kilometers (36,480 acres) and the riparian woodland 645.69 square kilometers (159,554 acres). Fauna associated with the study area are presented in Appendix A. 5 Figure 1. Study Area Location. The geographic and climatic conditions produce several biologically rich habitats in the lower Sacramento Valley. Historical reconstructions depict a landscape composed of large areas of open grassland situated between riparian forests growing along natural river levees (CSUC 1999; West et. al 2007:24). A vast freshwater marsh was located where the Cosumnes and Mokelumne rivers converged and entered the Sacramento River. Paleontological evidence indicates these habitats were present for the last 6000 years (West et al. 2007:24). Freshwater Marsh Historical reconstructions indicate that freshwater marshes occurred on either side of the Sacramento River and in the southwestern portion of the study area (CSUC 1999; Küchler 1977). Early accounts 6 Figure 2. Historic Vegetation Map. estimate that “areas of tule” occupied approximately 2175.6 square kilometers (537,600 acres) of the lower Sacramento Valley (Thompson 1961:307). This included areas extending up the current confluence of the Cosumnes and Mokelumne rivers near Thornton, and southwest into the Sacramento and San Joaquin Delta (Küchler 1977). Figure 2 depicts habitat locations prior to extensive Euro-American settlement and development circa 1900. This map indicates that freshwater marsh habitat once extended up the Cosumnes River to its confluence with Laguna Creek. Figure 2 was created by combining data from the 1999 CVHMP Pre-1900 vegetation map (CSUC 1999) and the SEFI Delta Recreation map (SFEI 2012). Each of these are, in turn, based on primary and proxy paleontological, geological, and hydrologic data, which indicate that approximately a third of the study area consisted of freshwater marsh. 7 Freshwater marshes comprise some of the most extensive ecosystems in the state. Prior to reclamation, it is estimated that almost 500,000 acres (202,343 hectares) around the confluence of the Sacramento, San Joaquin, American, and Cosumnes rivers was freshwater marsh (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:34 and references therein). By 1930, less than 60,000 acres (24,281 hectares) remained. Despite its former abundance, no consistent definition of freshwater marsh habitat has been developed (Schulz 1981:16). This is reflected by the numerous terms used to describe this habitat type. Freshwater marsh was referred to as tulares initially by the early Spanish, later tule marsh (Küchler 1977; Thompson 1961) and more recently as fresh emergent wetland (Kramer 2003); or, less accurately, the Delta since American settlement (ARNHA 2004; Pierce 1988). The most common term, however, is simply wetlands (CSUC 2008), although this can encompass a wide range of both permanent and seasonally flooded habitats. Thus, to avoid confusion the term freshwater marsh will be used to describe locally permanent wetlands of comparably consistent vegetation and other biotic composition. Freshwater marsh soils are typically wet, ranging from very poorly to somewhat poorly drained, with a high water table that is protected by natural river levees (USDA 1991). The anaerobic condition of these soils leads to the development of peat and supports a variety of hydrophytic grasses such as tule (Scirpus spp.), cattail (Typha spp.), sedge (Carex spp.) and rush (Juncus spp.) (Ingebritsen et al. 2000). The seeds, rhizomes, and shoots of these plants are seasonally edible, with the common tule (Scirpus acutus), in particular, contributing to the indigenous diet and providing principal raw material for the construction of houses, boats, and mats (ARNHA 2004:83; Levy 1978:406; Schulz 1981:16, 17; Wilson and Towne 1978:392). Within the study area, freshwater marsh is sometimes bordered by flood-tolerant trees, such as willow (Salix sp.) and Fremont’s cottonwood (Populus fremontii) that transition into riparian woodland in better drained areas. Freshwater marsh in the lower Sacramento Valley can be subject to significant tidal action. For example, ocean tides in the San Francisco Bay are observed five to six hours later in the Cosumnes River and Sacramento River flows as far north as Verona near the Feather River confluence (Gilbert 1917:15; Ingebritsen et al. 2000; Konrad 2012; Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:22). Prior to 1921, a saltwater interface 8 extended up the Sacramento River as far as Courtland, although saltwater encroachment into the study area was inhibited by the presence of natural levees and the western Delta islands, particularly Sherman Island located just west of Stockton. Seasonal flooding in the winter and spring also helps to prohibit the upstream intrusion of saltwater. Most of the primary plants and fish in the freshwater marsh habitat can tolerate higher than average levels of salinity as well. The most abundant faunal resource found in the freshwater marsh habitat is fish (see Table 3). Fish inhabiting the freshwater marsh prefer slow water environments. These fish include Sacramento perch (Archoplites interruptus); tule perch (Hysterocarpus traskii); hitch (Lavinia exilicauda); Sacramento blackfish (Orthodon microlepidotus); and Sacramento sucker (Catostomus occidentalis). Thicktail chub (Gila crassicauda), now extinct, were also abundant in the slow waters of the freshwater marsh. Causes for their extinction are largely linked to the removal of the tule beds for agriculture and the introduction of predacious bass species in the late 19th century (Moyle 2002:59, 182). Sacramento splittail (Pogonichthys macrolepidotus) can also be found in freshwater marshes, although they are also found in the swifter and cooler waters of the riparian woodland. Avian species common to the freshwater marsh consist of resident and migratory species. Residents include the great blue heron (Ardea herodias); the great egret (Egretta thula); pie-billed grebe (Podilymbus podiceps); American bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus); common moorhen (Linula chloropus); American coot (Fulica americana), and a limited number of waterfowl. Raptors such as the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) may forage in the area, but it is not their preferred habitat. Additional common residents include shorebirds such as the long-billed dowitcher (Limnodromus scolopaceus) and the redwing blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus). Migratory birds include waterfowl and a few other species. The lower Sacramento Valley is located along the Pacific flyway. As a result, an estimated 1.5 million ducks and 750,000 geese utilize the wetlands found in the Sacramento Valley (Bellrose 1976:21, 22; Northern California Water Association 2013). This annual visitation begins in the late fall and continues into the spring, with the greatest number 9 of migrants present between November through February. For example, the 35,000 acre Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge estimates that over three million ducks and one million geese visit the refuge during the winter migration (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2013). Migratory species commonly observed in the study area include whistling or tundra swans (Cygnus columbianus), geese (e.g., Canada goose [Branta canadensis moffitti]; greater white-fronted goose [Anser albifrons frontalis], lesser snow goose [Chen c. caerulescens]), and dabbler ducks (e.g., mallard [Anas platyrhynchos], pintail [Anas acuta], green-winged teal [Anas carolinensis], American widgeon [Anas americana], gadwall [Anas strepera]; and northern shoveler [Anas clypeata]). Although migratory, populations of Canada geese and mallards and other waterfowl are known to breed in the study area, increasing their seasonal availability. Other migratory birds include the lesser and greater sandhill crane (Grus canadensis) who migrate into the study area in October through mid-March (Cosumnes River Preserve 2010). The white pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) is also a frequent late winter through spring visitor. Unlike fish and birds, most mammals, the reptiles, and amphibians of the freshwater marsh are found in adjacent habitats as well. The largest mammal was the tule elk (Cervus elaphus nannodes) which also inhabited grassland and riparian woodlands. Elk are no longer found in the study area, but approximately 500,000 are estimated to have inhabited the state in herds numbering between 6 and 40 animals in aboriginal times (Bartolome et al. 2007:370; McCullough 1969:25). Other mammals that may be encountered in the freshwater marsh are river otter (Lontra canadensis), spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius), and mink (Mustela vison). Reptiles and amphibians include western pond turtle (Actinemys maramorata), western toad (Bufo boreas), Pacific chorus frog (Pseudacris egilla), and California red-legged frog (Rana draytonii). The freshwater marsh is also home to the bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) that was introduced in the early 20th century from the east coast (Zeiner et al. 1990a). The freshwater mussel, Anodonta nuttaliana can also be found on the periphery of the freshwater marsh, in low gradient, low elevation lentic habitats such as sloughs, permanently flooded marshes, and sandbars at the mouths of tributary streams (Nedeau et al. 2005:22). 10 Grassland The grassland habitat of the study area is characterized as a relatively flat landscape of grasses, forbs, and isolated oaks that gently rise to meet the Sierra Nevada. The pre-1900 distribution of grasslands (see Figure 2) comprised the largest habitat in the study area. (ca. 646 square kilometers/160,000 acres). Although habitat boundaries may have changed little over time, more than fifty percent of grassland habitats have been replaced by agricultural and urban development (Heady 1988:495). Two important subhabitats that occur in the grasslands, vernal pools and seasonal wetlands, are described below. Grasslands are a diverse ecosystem that responds to variations in soil nutrients, temperature, and moisture (Bartolome et al. 2007:383). Grasslands in the study area occur on the San Joaquin series soils that consist of well to moderately well drained soils that formed in mixed but predominantly granitic alluvium (Soil Survey Staff 2006; USDA 1991). They are moderate in organic matter and are underlain by a clay hardpan cemented with iron, silica, or both. The sediments are generally loamy, but given their high clay content and slow permeability, they are also subject to flooding (Heady 1988; USDA 1991). Historically grassland habitats included large populations of perennial bunch grass such as purple needlegrass (Nassella pulchra), nodding needlegrass (Nassella ceruna), and blue bunchgrass (Festuca idahoensis), as well as many forbs, broad-leaved herbs, and bulbs (Bartolome et al. 2007:370-371; Heady 1988:495-497). These were interspersed with isolated or small stands of trees, such as buckeye (Aesculus californica), oaks (primarily Quercus lobata), and bushes (Heady 1988:495). In spring and summer, large areas of the grassland habitat were covered with herbaceous wildflowers, such as clover (CVHMP 2008). Clover (Trifolium willdenovii) was an important food for local Native Americans as it was the first fresh herb available after winter (Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:309). In fact, the timing of the Nisenan spring flower dance depended on the emergence of clover (Bartolome et al. 2007:376; Levy 1978:403; Wilson 1972:37-38). Drought is the principal threat to perennial grasses, as it reduces their sustainability and quantity. However annuals, which now dominate the grassland, remain dormant as seeds during the summer and other dry times, greatly increasing their ability to survive droughts (Heady 1988:499). 11 Fauna found in the grassland habitat include a variety of mammals, birds and some reptiles. The largest mammals were artiodactyls, i.e., tule elk, black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus), and pronghorn (Antilocapra americana). As already mentioned, tule elk were certainly abundant, but pronghorn even more so, with some estimates placing their number in the millions prior to the 1850s with herds of 2000 to 3000 animals (Bartolome et al. 2007:370). Black-tailed deer are not as gregarious as pronghorn forming either small groups of three to four composed of females and juveniles or solitary males. Statewide densities of black-tailed deer average 18 to 60 individuals per square mile, but densities can range from 5 to 104 animals per square mile based on forage availability and season (Zeiner et al. 1990c:352). Black-tailed deer also tend to prefer brush for cover so it is unlikely they would have been found grazing in the grasslands too far from such protection. The black-tailed deer of the lower Sacramento Valley are a resident subspecies of mule deer which do not migrate into the Sierra Nevada during the summer (ARNHA 2004:153). Carnivorous mammals found in the grassland include coyote (Canis latrans), badger (Taxidea taxus), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), and long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata). Two lagomorphs and several rodent species are also found here. Lagomorphs include black-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) and desert or Audubon’s cottontails (Sylvilagus audubonii). In the past, seasonal flooding of the grassland would have reduced suitable habitat, and likely restricted the overall population of these animals. The same may be true for the California or Beechey ground squirrel (Spermophilus beecheyi), the largest rodent that inhabits the grasslands. Other rodents common to grassland habitats are Heermann’s kangaroo rat (Dipodomys heermanni), California vole (Microtus californicus), and deer or white-footed mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus). Numerous birds, such as raptors, vultures, and perching birds are found in the grassland. Raptors found here include the year round resident red-tailed hawk, northern harrier (Circus cyaneus), and migrant Swainson’s hawk (Buteo swainsoni). The turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) is also common in this habitat. The American crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos), yellow-billed magpie (Pica nuttalli), and American robin (Turdus migratorius) are common perching birds seen in the grassland, although they also frequent riparian 12 woodlands. Some waterfowl also frequent the grasslands for nesting or feeding, including Canada geese, greater white-fronted geese, and the lesser snow geese. On the edge of the grassland bordering the foothill woodland/chaparral, are also California quail (Callipepla californica). Lastly, snakes of the grasslands include common kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula), gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer), common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis), and occasionally western rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis). Lizards include southern alligator lizard (Elgaria multicarinata) and western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis), and amphibians include western spadefoot toad (Spea hammondii). An important sub-habitat of the grassland is vernal pools. Vernal pools occur where impervious layers of clay underlie the surface soil. Paleontological evidence indicates vernal pools have been a part of the California landscape for tens of thousands of years (Holland and Jain 1988:516, 517). Vernal pools fill with water in the winter and dry up by the end of the spring. Seeds and small aquatic life associated with vernal pools become dormant, waiting for the next wet season. Plants and animals adapted to vernal pools include a variety of crustaceans, such as California linderiella fairy shrimp (Linderiella occidentalis), vernal pool fairy shrimp (Branchinecta lynchi), and tadpole shrimp (Lepidurus packardi), a variety of beetles (Agabus sp.), true bugs (Hemiptera sp.) and solitary bees (genus Andrena), as well as spadefoot toads, tiger salamanders (Ambystoma californiense), and waterbirds such as killdeer (Charadrius vociferous), avocet (Recurvirostra americana), and greater yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca) (Keeler-Wolf et al. 1998:9). Cinnamon teal (Anas cyanoptera) and mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) also frequently utilize vernal pool habitats. Vernal pools in the study area are of two scales: large pools of 3500-4000 square meters (0.86 to 0.99 acres) and clusters of small pools within a ten hectare (25 acre) area (Holland and Jain 1988:520). The second important grassland sub-habitat is seasonal wetlands. Most grassland habitat occurs along low lying basins between natural river levees and alluvial fan deposits from the Sierra Nevada. In the spring, these basins would traditionally flood, inundating areas of grassland. Water would remain until it evaporated or river levels fell below that of the flood basin (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:30). Given these 13 conditions, extensive seasonal wetlands would have formed each year in the lower Sacramento Valley. Soil morphology and historical data suggest that the lower 15 km (9.32 miles) of the Cosumnes River supported a seasonal wetland prior to hydraulic mining practices upstream in the late 1800s (Florsheim and Mount 2003:313). Floodplains of this sort are critical for the growth and development of Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and several native cyprinids (minnows) such as Sacramento blackfish and Sacramento splittail (Moyle 2002:256; Moyle et al. 2007; Sommer et al. 2011:81; Swenson et al. 2003). Native amphibians also benefited from seasonal wetlands for breeding habitat (Zeiner et al. 1990a). Annual burning of the grasslands by indigenous peoples further helped to rejuvenate floodplain soils and clear senescent vegetation, improving the habitat for fish (Bot and Benites 2005:27; Lightfoot and Parrish 2009:98). Along the northwestern and western edge of the study area, grassland merges with the Valley Oak Woodland or Valley/Foothill Hardwood Forest. Grassland is dominated by valley oak (Quercus lobata) and varies from patchy to relatively dense stands of trees depending on water availability and soil depth. The understory is largely composed of grasses and forbs resembling grassland habitats. The Valley Oak Woodland typically occurs at elevations averaging 150-240 meters (492-787 feet) which are largely outside of the study area (Allan-Diaz et al. 2007:315-318). Fauna in this habitat include black-tailed deer, coyote, dusky-footed woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes), western grey squirrel (Sciurus griseus), mourning dove (Zenaida macroura), and California quail (Zeiner et al. 1990b:168). Riparian Woodland Riparian woodlands in the study area comprise both oak and river-bank forests that integrate with valley/foothill hardwood habitats (Meyer and Rosenthal 2008:34). Historical reconstructions suggest that approximately twelve percent of the study area was riparian woodland. Soils associated with riparian woodlands are typically coarse textured alluvial loams with a relatively high water table (CVHMP 2008; Thompson 1961:309). These woodlands can be up to a several miles wide on larger rivers or narrow bands 14 along banks of smaller streams and edge of freshwater marshes with tree density proportional to the size of the waterway and natural levees (ARNHA 2004:13; Thompson 1961:294, 306, 315). Rivers bordered by riparian woodlands include portions of the American and lower Sacramento rivers as well as the Cosumnes, Mokelumne, and Dry and Laguna creeks (see Figure 2). Riparian woodlands were of greatest width along the lower Sacramento River where some were four to five miles wide (Thompson 1961:307). Prior to modern levee construction, natural river levees associated with these waterways rose 1.5 to 6 meters (5 to 20 feet) above the surrounding land (Thompson 1961:29). Riparian woodlands strengthened the levees and acted as natural windbreaks, reducing evaporation, transpiration, and wind damage. Dominant canopy species associated with the riparian habitat includes California sycamore (Platanus racemosa), valley oak, Fremont’s cottonwood, white alder (Alnus rhombifolia), Oregon ash (Fraxinus latifolia), and numerous species of willows. Prior to Euro-American settlement, some oaks and sycamores were 75 to 100 feet tall (Thompson 1961:307) and interspersed with California black walnut (Juglans californica) (Schulz 1981:14; Thompson 1961:307, 311). Understory vegetation in the riparian habitat includes California box elder (Acer negunde californicum), coyotebrush (Baccharis pilularis consanguinea), blackberries (Rubus spp.), wild rose (Rosa californica), and various annual and perennial herbaceous species. Resident vines that inhabit the riparian woodland are California grape (Vitus californica), poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum), and Dutchman’s pipe (Aristolochia californica). Based on historical accounts, most of the riparian woodland along the Sacramento River had been destroyed by 1868 when it was logged for fuel and cleared for agricultural fields, particularly orchards (Thompson 1960:311-312). A diverse and abundant fauna is found in riparian woodlands. This includes black-tailed deer and rodents, including the American beaver (Castor canadensis), the western gray squirrel, the dusky-footed woodrat, Botta’s pocket gopher (Thomomys bottae), and the deer or white-footed mouse. Carnivores include mountain lion (Puma concolor), bobcat (Lynx rufus); and ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) and species such as river otter, mink, and long-tailed weasel found in adjacent habitats. The same is true for omnivores like coyote, gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) and striped and spotted skunks. Raccoons (Procyon 15 lotor), by contrast, may have been limited to the riparian woodlands. The now extinct California grizzly bear (Ursus arctos californicus) and gray wolf (Canis lupus) were especially abundant in this habitat (Jameson and Peeters 2004:79-80). Many birds and fish but fewer reptiles and amphibians were found in riparian woodlands. Resident birds included double-crested cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus), red-tailed hawk; wood duck (Aix sponsa); belted kingfisher (Ceryle alcyon); mourning dove (Zenaida macroura); and western scrub-jay (Aphelocoma californica). Several woodpeckers and their kin are also found in riparian woodlands, including Nuttall’s woodpecker (Picoides nutallii), downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens), and northern flicker (Colaptes auratus). Resident reptiles include the western pond turtle and snakes. Western pond turtles favor marsh and river habitats with slow moving waters, submerged logs, rocks, floating vegetation, and mud banks for basking and cover. Other reptiles and amphibians of the riparian woodland include snakes such as the racer (Coluber constrictor) and endangered giant garter snake (Thamnophis gigas), Pacific chorus frog, California slender salamander (Batrachoseps attenuatus), and California newt (Taricha torosa). Prior to the deleterious effects of hydraulic mining and agriculture, anadromous fish, such as Chinook salmon, white and green sturgeon (Acipenser montanus and A. medirostris), and Pacific and river lamprey (Lampetra tridentata and L. ayresii), would migrate through most of the study area rivers and creeks. Chinook salmon had four runs on the Sacramento River but only a fall run was known on the Cosumnes River (Moyle 2010, personal communication; Yoshiyama et al. 2001:111). Accurate salmon counts for the Sacramento River are lacking prior to the mid 20th century, but a Wintun informant reported that they were abundant enough to feed 200 to 300 people for two to three weeks (Yoshiyama et al. 2001:143). Fallrun spawning populations along the main stem of the Sacramento River (approximately 67 miles) averaged 217,100 annually during 1952–1959; 136,600 in the 1960s; 77,300 in the 1970s; 72,200 in the 1980s; and 48,000 from 1990 to 1997 (Yoshiyama et al. 2001:145). Cosumnes River numbers are smaller, but prior to 1929 they were described as “considerable” equaling those on the Mokelumne, which produced at least 3800 pounds of salmon in 1929 (Yoshiyama et al. 2001:110). From 1953 to 1959 16 approximately 500 to 5000 Chinook salmon were estimated in the Cosumnes River although the historical average was approximately 1000. No salmon were recorded in the Cosumnes River after 1988 until their reintroduction in 1998 (Moyle 2010, personal communication; Yoshiyama et al. 2001:112). Other native fish present in the faster water riparian habitats of the study area include hardhead (Mylopharodon conocephalus), Sacramento pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis), and Sacramento splittail, with the the latter two found in slow water habitats as well. Summary The descriptive utility of vegetation communities, notwithstanding their boundaries and biotic composition, can change over time, transition zones providing varied opportunities for humans and animals alike. Soil studies indicate that the general locations have been stable for many centuries, but paleoenvironmental data indicate that their volume and community boundaries have waxed and waned over time in response to climatic forces (see Chapter 3). Anthropogenic factors are another source of community change, notably aboriginal fire regimes and the devastation wrought by Euro-American occupation after the 1849 Gold Rush. Native American fire regimes helped to rejuvenate the soil in seasonal grassland wetlands. Fire management also helped to create and support the complex environmental mosaic and biological diversity that characterized the study area (Lewis 1982:51-52; Parrish and Lightfoot 2009:99). Euro-American occupation of the study area, by contrast, produced swift, deleterious, and permanent changes to the environment. In less than 100 years, over 85 percent of the freshwater marsh, grassland, and riparian habitats present in 1849 were destroyed (CSUC 2003:15). What early mining and agricultural practices failed to destroy, were subsequently consumed by 20th century river channelization and urban sprawl. As a result, less than four percent of the historic habitats of the lower Sacramento Valley remain. Most of the native fish, large mammals, and carnivores are now extinct, extirpated, or endangered. Migratory bird and 17 fish populations have been significantly reduced, with Central Valley waterfowl decreased from an estimated six to ten million birds in 1935 to only three to five million in 1974 and Cosumnes River salmon extirpated sometime after 1959 (Bellrose 1976:17; Ducks Unlimited 2013; Yoshiyama et al. 2001:112). This implies that although plant and animal resources in the study area likely shifted over time due to anthropogenic and climatic factors, and that these changes ought to be reflected in archaeological deposits. More than this, it suggests that the present landscape is at best an indirect and imperfect reflection of the environment used by prehistoric people. This implies, in turn, that the study of zooarchaeological and paleobotanical collections provide one of the only avenues available to reconstruct the prehistoric ecology of the lower Sacramento Valley.