late 19th century, Indonesia

advertisement

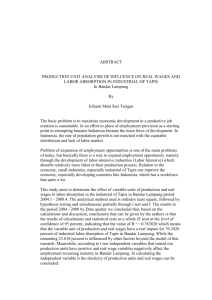

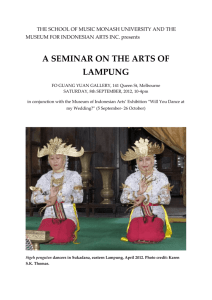

Lampung Textiles Textiles are a part of our everyday lives and have been for thousands of years. Some textiles are purely utilitarian like towels or curtains. Others offer a look into the culture, history and economics of a family. Some textiles are used only for specific occasions. This is true of American history and Indonesian history. This month we will at how special woven textiles were used in 19th century Indonesia. Lampung, provinsi (province), southern Sumatra, Indonesia, bounded by the Java Sea to the east, the Sunda Strait to the south, the Indian Ocean Figure 1 to the west, and Sumatera Selatan (South Sumatra) Ceremonial Cloth province to the north and Late 19th century, Lampung culture, Sumatra, Indonesia northwest. It includes the 30 x 27 ¼ inches islands of Sebuku, Sebesi, Cotton Sertung, and Rakata in Sunda Strait. The area formed part of the kingdom of Kantoli in southern Sumatra in the beginning of the 6th century and in the 14th century was included in the Hindu Majapahit Empire of eastern Java. Hindu and Buddhist archaeological remains have been found at Palas, Talangpadang, Liwa, and Mount Besar. In the 16th century, Lampung was part of the Muslim state of Bantam (now Banten) under Hasanuddin (ruled 1552–70). The Dutch incorporated Lampung into their colonial empire in 1860. It became part of the Republic of Indonesia in 1950. The southernmost portion of the Barisan Mountains runs the length of the province from the northwest to southeast and is surmounted by volcanic cones including Mounts Batai, 5,518 feet (1,682 metres) and Tebak, 6,939 feet (2,115 metres). The mountains are flanked by narrow coastland on the southwest and by rapidly descending highlands on the northeast. The eastern lowland area of Lampung stretches from the foothills of the mountains to the belt of swamps along the eastern coast. The Sekampung, Seputih, and Tulangbewang rivers descend the eastern slopes of the mountains and drain eastward into the Java Sea. Mangrove and freshwater swamp forests are found along the coast; tropical lowland evergreen rainforests extend from the coastal swamps into the mountains. Most of the population is engaged in agriculture; rubber, tea, coffee, soybeans, sweet potatoes, corn (maize), peanuts (groundnuts), copra, and palm oil are produced. Deep-sea fishing is also important. Industries include wood carving, food processing, cloth weaving, mat and basket making, and the production of handmade paper. Road and railway transport is confined to the foothills of the Barisan Mountains and link Tanjung Kurang, the provincial capital, with Kotabumi, Panjang, and Telukbatung. The eastern half of the province relies mainly on riverine transport. The population is a mixture of Malay, Javanese, and Minangkabau. The Javanese are the most numerous because of a large influx of rural Javanese into Lampung in the early 20th century. Area 13,662 square miles (35,384 square km). Pop. (2000) 6,741,439. Figure 2 19th century Indonesia, Sumatra, Lampung province, Piya, Wai Ratai River region Cotton, L. 31 x W. 28 1/2 in. (78.7 x 72.4 cm) Textiles-Woven Gift of Anita E. Spertus and Robert J. Holmgren, in honor of Douglas Newton, 1990 Accession Number: 1990.335.22 Situated along the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, a crucial trade route since antiquity, the Lampung region of southern Sumatra has long been a crossroads of cultures and artistic traditions. Lampung's sumptuous textile traditions reflect the enormous wealth brought to the region through the trade in pepper, which grew in abundance. The women of Lampung developed a rich variety of textiles that included ceremonial forms as well as other types, which were used as clothing. Among the most visually striking Lampung textiles are the intricately woven tampan, small square-shaped cloths Figure 3 Ceremonial textile (palepai) late 19th century, Indonesia Overall: 135 x 27 in. (3 m 42.901 cm x 68.58 cm) Cotton and metal-wrapped cotton yarn Credit Line: Dallas Museum of Art, the Steven G. Alpert Collection of Indonesian Textiles, gift of the McDermott Foundation Object Number: 1983.80 that were exchanged during important rites of passage. Tampan were owned and used by virtually every Lampung family to consecrate ritual occasions and to assist each individual as he or she progressed through the diverse ceremonies that marked the various stages of life. Tampan were displayed or exchanged at both birth and death, at marriages, circumcisions, and ceremonies marking changes in social rank. They served as the focal point for ceremonial meals, as the seat for the elders who oversaw traditional law, and were tied to the ridge poles of newly built houses. They were a sacred force that bound society together. Up until the 1920s, Lampung had a rich and varied weaving tradition. Lampung weaving used a supplementary weft technique which enabled colored silk or cotton threads to be superimposed on a plainer cotton background. The most prominent Lampung textile was the palepai, ownership of which was restricted to the Lampung aristocracy of the Kalianda Bay area. There were two types of smaller cloths, known as tatibin and tampan, which could be owned and used by all levels of Lampungese society. Weaving technologies were spread throughout Lampung. High quality weavings were produced by the Paminggir, Krui, Abung and Pesisir peoples. Production was particularly prolific among the people of the Kalianda Bay area in the south and the Krui aristocracy in the north. The oldest surviving examples of Lampung textiles date back to the eighteenth century, but some scholars believe that weaving may date back to the first millennium AD when Sumatra first came under Indian cultural influence. The prevalence of Buddhist motifs, such as diamonds, suggests that the weaving traditions were already active in the time when Lampung came under the Buddhist Srivijayan rule. There are similarities between Lampung weaving and weaving traditions in some parts of modern-day Thailand that experienced cultural contact with Sriwijaya. Lampung textiles were known as 'ship cloths' because ships are a common motif. The ship motif represents the transition from one realm of life to the next, for instances from boyhood to manhood or from being single to married and also represents the final transition to the afterlife. The finest tampans were worn or displayed during ceremonies or used as dowry items. Gifts presented during marriages were wrapped in the tampan. The artist of a particular ceremonial cloth repeated lines and shapes to create patterns and rhythm on the cloth. The symmetrical use of color and abstract patterns gives the cloth a feeling of balance. Tampans occur in two regional styles and in two primary colors. Those woven in blue depict the secular realm, those in red the sacred. Examples from the inland mountains show stylized natural or domestic subjects and geometric designs, while those from the coast (tampan pasisir) display richly detailed scenes of ships and other motifs. Although tampan were used by all social classes, the ornate tampan pasisir, such as the work in Figure 1, were a prerogative of the nobility. The fanciful ships that appear on tampan pasisir, steered with the exterior rudders distinctive to Indonesian and South Asian vessels, may recall the forms of large trading ships that plied the seas in precolonial times. Shown in cross-section, the ship on this work is a virtual floating palace. Within it, a single human figure, almost certainly a person of authority, lies in a cabin in the stern, accompanied, perhaps, by an attendant. Forward of the cabin, a helmsman guides the ship with a steering oar. In the central cabin, a group of men (identified by the presence of the kris [daggers], in their belts) play a group of instruments similar to a traditional Javanese gamelan orchestra. The crew appears on deck and the skies above and sea below teem with fantastic life. Replete with images of abundance and regal ease the work portrays an idealized world of opulence, beauty, and power. In times of dire economic need, a family may sell their tampans to raise money. Figure 4 Production of many fine cloths blossomed in the late nineteenth century as Lampung grew rich on pepper production, but the devastating eruption of Krakatoa in 1883 destroyed many weaving villages in the Kalianda area. By the 1920s the increasing importance of Islam and the collapse of the pepper trade brought production to a halt. Today Lampung textiles are highly prized by collectors. Due to major changes in Indonesia’s social and economic structures over the past centuries, tampan textiles are rarely made in Sumatra today. Students will be more familiar with the ever popular batik designs from modern Indonesia. Catastrophic: An artist's impression of the historic 1883 In present day Sumatra and on the other Indonesian islands, most eruption of Krakatoa people have adopted Western style dress, Many ancient customs have been abandoned due to the rushed schedules of modern life and the cultural influences of globalization, However, some individuals maintain aspects of the old customs, such as wearing items of traditional clothing during special occasions or as apart of religious celebrations. In the Indonesian capital of Jakarta, businessmen in Western-style suits can sometimes be seen wearing various kinds of ceremonial textiles draped over their shoulders. CRITICAL THINKING 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Examine this cloth. What do you think the abstract shapes represent? Show where an animal can be found on this cloth. Discuss where the artist repeated colors and lines Show where shapes are repeated o n this cloth. If you could plan a ceremony using this cloth, how would it be used? VOCABULARY 1. 2. 3. tampan- small square-shaped woven cloths that were exchanged during important rites of passage weaving- to form cloth by interlacing strands of threads or yarn; specifically : to make (cloth) on a loom by interlacing warp and filling threads warp- a series of yarns extended lengthwise in a loom and crossed by the weft 4. weft- a filling thread or yarn in weaving Activities 1. 2. Use the design on a tampan as in inspiration to create your own story. Have the kids get into small groups and give them each a cloth. It can be a bandanna or a twin size sheet. Whatever you have and don’t mind having to wash later. ;o) Direct the students to think about how they could use this special cloth in a ceremony. Wedding, new baby, graduation, a new home, becoming an adult….. 3. Look at the images from a friendship quilt and discuss their history with students. Then have them compare and contrast the Indonesian culture and their textiles with the American quilts. Figure 5 Friendship Quilt photograph by The International Society of Daughters of Utah courtesy the Pioneer Memorial Museum In the 1800s women commonly formed quilting groups. Their quilts offer clues to the nature and experiences of western migration and to the ways in which women gathered for social, artistic, and practical purposes. Quilt making and the quilts themselves served various purposes. In addition to their function as bedding, quilts also served as records of family or community history, observations of surrounding landscape, and documentation of life cycle events such as births and marriages. Certain quilting patterns were based on repeated motifs. Some images were symbolic and many were derived from nature, such as the dove, which represented innocence; the peony, which stood for healing; and the pine tree, which foretold fidelity and everlasting life. Although individual women made their fair share of quilts, many were made at quilting bees, where women shared in the cutting, stitching, quilting, and local gossip. ("Quilting Groups: Creating Through Camaraderie" in "Collaborations: Drawn Together".) In the mid to late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries every community had it's quilt bees and most followed a similar pattern. Women spent long winter months piecing tops and over the summer months called on their friends and neighbors to help quilt them. No one wanted to miss a quilting as this was a major social occasion and chance for gossip, if you weren't there yours could be among the names bandied about over the frame! (or frames, often more than one quilt was worked on at a bee in the summer, when the quilting was outdoors). Children were called upon to keep the needles threaded and less skilled quilters and young ladies were often relegated to KP duty, it paid to polish your quilting stitch! Perhaps the most festive Quilting Bees were held to quilt a bride’s quilt. Traditionally this quilt would be the thirteenth quilt a young girl had made, and displayed her finest work. The time between engagement and wedding was a flurry of quiltings as none of the thirteen quilts were quilted before the engagement. The most expensive part of a quilt was the backing and batting and this investment was not made until it was certain the quilts would be needed to set up housekeeping. The quilt bee was a party as much if not more than a working occasion and a lady made every effort Figure 6 to put on her best for her friends and Rev. Nadal's "Baltimore Album" Quilt neighbors. At the end of the day the 1847 men joined the ladies for a festive Nadal, Bernard H., original owner supper and perhaps a barn dance. These 1983.0866.01 events were particularly cherished by the women of the Great Plains and For background story see western states as it was a rare http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/ opportunity for them to see other object/nmah_556185 women, they spent most of their days with their own families and chores and might only see others every few months and not at all in the winter. It might be a four or five hour or more journey to the nearest neighbor, a truly perilous trip in winter. Some women were very fussy as to who was invited to a quilting, wanting only the most skilled to work on her quilts. Occasionally the stitches of a less skilled quilter were removed after the bee and redone by the quilts owner. Pride was taken in ones stitches! Quilt Bees still take place today though they are more likely to take the form of a church or charity organization which quilts to raise funds for well deserving causes than as the social occasion which also resulted in the completion of a necessary but tedious task. 4. After viewing a friendship quilt image and discussing it, give each student a sheet of paper divided into four squares to use as a quilt square template. Have the students use one block on their sheet of paper to create a quilt square representing what they wish for themselves and/or their classmates. To create the atmosphere of a quilting bee, allow students to chat and circulate a bit as they are working. As a written component for this lesson, ask students to write or dictate a paragraph explaining the section of the quilt they have created. When all the squares are done, have the class sit in a circle. The students were allowed to chat as they were working. What were they talking about? What do students imagine was going on in the room as the women were working together on the friendship quilt? If these were pioneer women who didn't often see each other and had little means of communicating, what might they have talked about? Have students display and describe their squares. After sharing their squares, have students copy their designs into the other three squares on the template. They can cut apart the four squares and keep one of their own squares. The other three are placed face down in a pile. Set up the piles for the students to pick from randomly for sampler making. Pass out another template. Each student makes a sampler by picking three designs made by other students and pasting them onto three squares on the template. Students can only trade in a square if they pick their own. The fourth square is for the student's design. When the samplers are complete, encourage volunteers to share. What wishes does the sampler show? What was it like using the work other people did to create a sampler? Was it easier than making four different designs themselves? Tie this back to the Indonesian textiles by asking students if they think it would have been much different to create a tampan for a bride? How many people do they think worked on the tampan?