Constantine I

advertisement

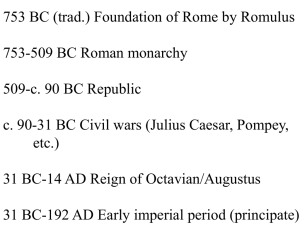

Constantine I From ABC-CLIO's World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras website http://ancienthistory.abc-clio.com/ Along with Diocletian, fourth-century-CE Roman emperor Constantine I, known as Constantine the Great, restored order to the Roman world and laid the foundation for the empire's success for centuries to come. During his reign from 306 to 337, his achievements were numerous, including reform of the coinage and the establishment of a new capital at Constantinople. He is important also for his military reforms and his introduction of many Germans into the Roman military. He is particularly significant for his conversion to Christianity. Indeed, his activities as the first Christian emperor of the Roman Empire had great consequences for the Catholic Church and for the Germanic peoples who inherited the empire in the fifth and sixth centuries. Constantine, whose Latin name was Flavius Valerius Constantinus, was born on February 27, probably sometime after 280 CE, in Naissus, Moesia (a Roman province in the Balkans). His father, Constantius I Chlorus, became caesar (deputy emperor) in 293. After his father separated from Constantine's mother, Helena, Constantine grew up in the Eastern Roman Empire at the court of Emperor Diocletian, located at Nicomedia in Asia Minor. In 305, Diocletian and his coemperor, Maximian, abdicated, and Constantine's father became caesar augustus, or emperor. Constantine joined Constantius I in a campaign in Britain, where his father died in 306. The Roman Army proclaimed Constantine emperor, but a series of civil wars immediately broke out over the question of imperial succession. One of the most critical moments in Constantine's struggle for power came in the year 312, when he fought his rival Maxentius, Maximian's son, for control of the Western Roman Empire. Constantine won that match in the Battle of Milvian Bridge (one of the bridges across the Tiber River to Rome), and the victory brought him possession of the ancient capital, Rome, and the western imperial title. Constantine's victory at Milvian Bridge was preceded by a great vision that was the starting point, if not the actual cause, of his conversion to Christianity. According to the contemporary Christian historian Eusebius in his biography of the emperor, Constantine said that, prior to the battle, he saw the sign of the cross in the heavens bearing the inscription "In this sign conquer." Another account tells that Constantine dreamed of being instructed to paint a Christian symbol on his army's shields. In any case, his triumph confirmed the validity of the vision and led him to accept Christianity. It was indeed in the following year that, along with the Eastern Roman emperor Licinius, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan (313), which legalized Christianity in the empire. Constantine then ruled the Western Roman Empire with a colleague in the east, Licinius, until 324, when he defeated Licinius in battle and reunited the empire. Constantine subsequently reigned as sole emperor, although often with his sons as caesars, until his death. Perhaps to foil a usurpation plot, although the true reason is unknown, Constantine ordered his wife Fausta and his eldest son and caesar, Crispus, killed in 326. In 330, on the site of the city of Byzantium, Constantine founded a new capital named for himself, Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey), and declared it the "second Rome." Rome itself continued to decline in political importance, and after a visit to mark the 20th anniversary of his reign in 326, Constantine never returned there. Constantine's reign had significant consequences for the Germanic successor kingdoms that emerged in the wake of the collapse of the Western Empire, as well as for much of early medieval Europe in general. As the first Christian emperor, he established an important model for numerous kings and emperors, including the great Frankish rulers Clovis I and Charlemagne. His relations with the Christian church also set an important precedent for later rulers in both the barbarian kingdoms and the Byzantine Empire (as the Eastern Empire came to be called). On two occasions, both interestingly after military victories—one that brought him control over the western half of the empire and the other over the entire empire—Constantine convened church councils to decide major issues of Christianity. The first council resulted in the Edict of Milan. The second of the councils, at Nicaea in 325, decided one of the fundamental tenets of the Christian faith: the equality of God the Father and God the Son. Constantine presided over the council and participated in debate, and his presence may have influenced the outcome. At the very least, it set the model for the involvement of the emperor in the affairs of the church and asserted the right and responsibility of the emperor to convene church councils. Constantine's involvement in the Council of Nicaea may also have led to the denunciation of the teachings of Arius—a priest from Alexandria, Egypt who taught that Jesus of Nazareth was not truly divine—and the declaration of Arianism as a heresy. Constantine, however, wavered in his support for orthodoxy and allowed the growth of Arianism in the empire. Consequently, the Germanic tribes living along the imperial frontier were evangelized by Arian Christians, and many of the tribes that converted to Christianity accepted the Arian version. Constantine's other legacy to the late Roman and early medieval world was his recruitment of Germans into the Roman Army. He was criticized by contemporaries and has been remembered by historians for the so-called barbarization of the army, which undermined Rome's ability to defend itself against other Germanic invaders. On the other hand, the promotion of more and more Germans to high-ranking military posts allowed the barbarians to identify themselves with the empire and its values and thus become Romanized. Constantine himself strove to be identified as a conqueror of the barbarian races. His wars against the Germans were intended to stabilize the frontier, which had proved particularly porous during the third century, and to provide Constantine a glorious military record to parallel his successes in the civil wars. Toward those ends, he fought border wars with the Alemanni along the Rhine River and faced the Visigoths along the Danube River. Constantine repelled the invaders and extended Roman authority, but unfortunately for the empire, his successes were short–lived. By the end of the fourth century at the latest, his settlements had broken down, and various Germanic tribes had crossed into the empire. Despite his fervent Christianity, Constantine waited until late in his life to be baptized. While on a military campaign, he became ill and could not make it back to Constantinople. He was baptized in Nicomedia and died near there soon afterward, on May 22, 337. MLA: "Constantine I." World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras. ABC-CLIO, 2014. Web. 6 Jan. 2014.