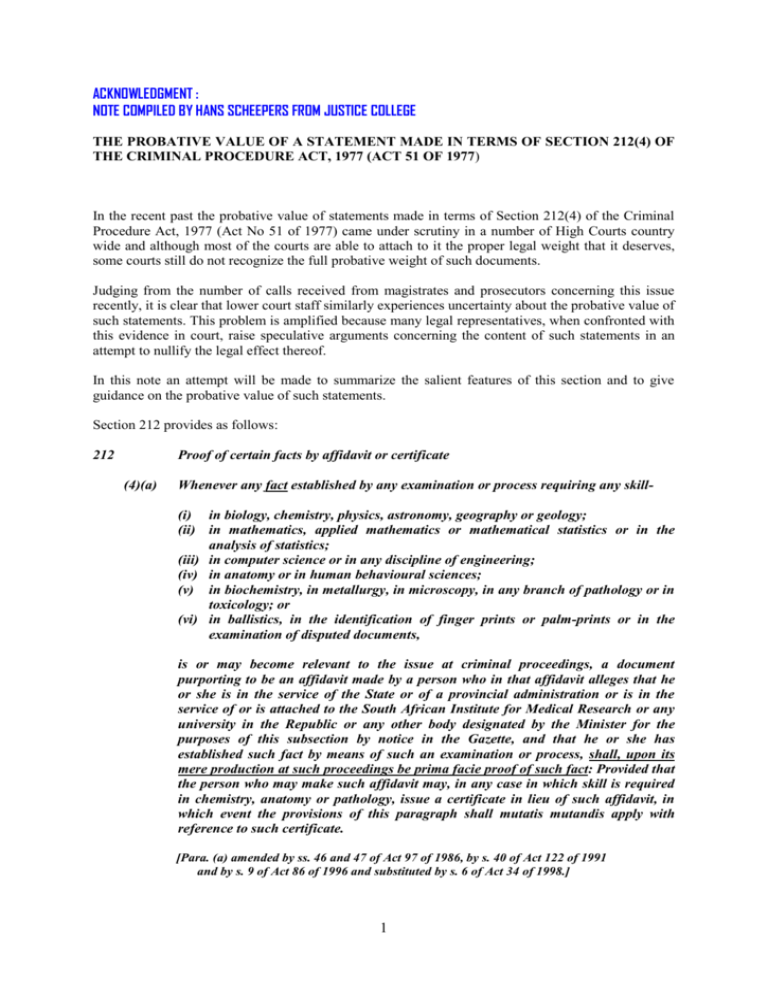

The Evidential Value of a Statement Made in Terms of Section 212

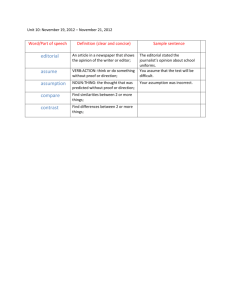

advertisement