ESM1: Monitoring Female Chimpanzees` Estrous Cycles Inoue and

advertisement

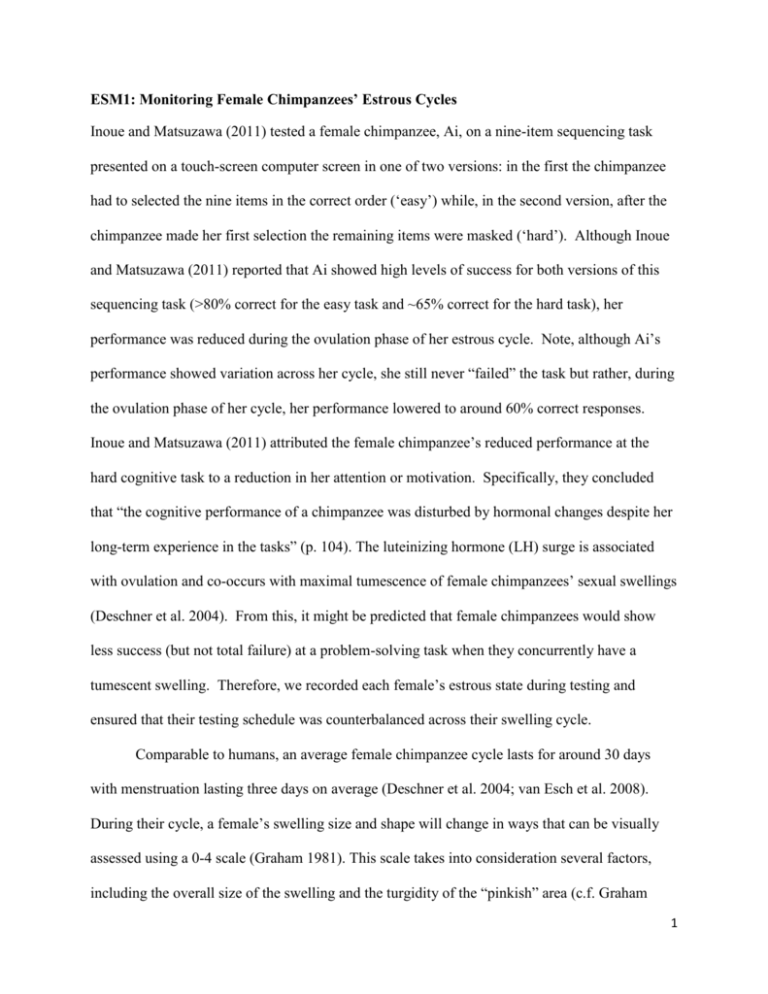

ESM1: Monitoring Female Chimpanzees’ Estrous Cycles Inoue and Matsuzawa (2011) tested a female chimpanzee, Ai, on a nine-item sequencing task presented on a touch-screen computer screen in one of two versions: in the first the chimpanzee had to selected the nine items in the correct order (‘easy’) while, in the second version, after the chimpanzee made her first selection the remaining items were masked (‘hard’). Although Inoue and Matsuzawa (2011) reported that Ai showed high levels of success for both versions of this sequencing task (>80% correct for the easy task and ~65% correct for the hard task), her performance was reduced during the ovulation phase of her estrous cycle. Note, although Ai’s performance showed variation across her cycle, she still never “failed” the task but rather, during the ovulation phase of her cycle, her performance lowered to around 60% correct responses. Inoue and Matsuzawa (2011) attributed the female chimpanzee’s reduced performance at the hard cognitive task to a reduction in her attention or motivation. Specifically, they concluded that “the cognitive performance of a chimpanzee was disturbed by hormonal changes despite her long-term experience in the tasks” (p. 104). The luteinizing hormone (LH) surge is associated with ovulation and co-occurs with maximal tumescence of female chimpanzees’ sexual swellings (Deschner et al. 2004). From this, it might be predicted that female chimpanzees would show less success (but not total failure) at a problem-solving task when they concurrently have a tumescent swelling. Therefore, we recorded each female’s estrous state during testing and ensured that their testing schedule was counterbalanced across their swelling cycle. Comparable to humans, an average female chimpanzee cycle lasts for around 30 days with menstruation lasting three days on average (Deschner et al. 2004; van Esch et al. 2008). During their cycle, a female’s swelling size and shape will change in ways that can be visually assessed using a 0-4 scale (Graham 1981). This scale takes into consideration several factors, including the overall size of the swelling and the turgidity of the “pinkish” area (c.f. Graham 1 1981). These factors can vary across individuals and across cycles for the same individual, but the benefit of this visual scale is that it can be used as an indicator of hormone levels without necessitating hormonal assays (Deschner et al. 2004). Deschner et al. (2004) concluded that the absolute size of a female’s swelling is not a reliable indicator of a female’s reproductive quality and a focus upon female swellings only enables intra-individual changes. To establish whether each of the 24 female chimpanzees tested in the present study followed a regular monthly estrous cycle, the appearance of each female’s sexual swelling was recorded (by S.A.P.) twice per week for three months prior to the commencement of the study. To ensure reliability, a photograph was taken of the female’s swelling once per week and assessed by two raters (S.A.P. and L.M.H.) who showed strong inter-rater reliability. In rare cases (<5%) of rating disagreement, an experienced member of the veterinary staff provided their opinion. Following Reichert et al. (2002), the females’ swellings were rated on a 0-4 scale, where 0 represents the most flaccid state of the swelling and 4 the most turgid. This three-month assessment revealed that nine of the 24 female chimpanzees followed a regular monthly swelling cycle (Table S1). The remainder showed no cycling patterns with regard to the shape and size of their swelling and remained classed as 0 throughout the assessment period. We note that the majority of the females tested in our study were on some form of contraceptive (Norgestrel/Estradiol, ParaGard®, or Implanon®, see Table S1 for details) and unfortunately we were only able to test two females that were on no form of contraceptive (and that had not had a hysterectomy). Whilst acknowledging that those females that exhibited sexual swellings following a regular cycle may not have been experiencing typical fluctuations in hormone levels (see also Proctor et al. 2011), we note the work of Bettinger et al. (1997) who reported that certain forms of birth control do not interfere with regular hormonal fluctuations 2 (see also Wagner and Ross 2013). However, we also note that these female chimpanzees would have experience more constant cycling than wild chimpanzees due to their birth control regimens which both inhibited pregnancy and controlled their cycling patterns. 3