Studies on materials and techniques to enhance clinical outcomes

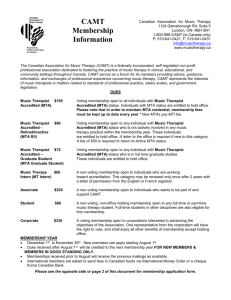

advertisement