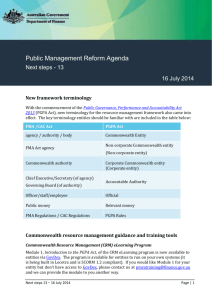

The independent Review of Whole-of

advertisement