File - David LaBelle

advertisement

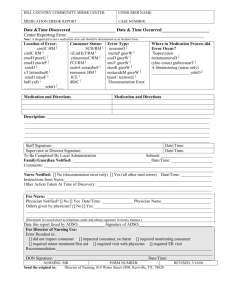

Running head: INPATIENT PEDIATRIC Inpatient Pediatric Medication Management David LaBelle Ferris State University 1 INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 2 Abstract An important part of a nurse’s career is the administration of medication. While there are several safety checks to help decrease the percentage of medication errors such as the five rights (right patient, right route, right medication, right time, and right dose), errors still can occur. Giving the correct dose of medication is especially important in the pediatric population as many of the drugs are based on weight and small amounts of drugs are administered (decimals may be used due to small doses) that further contribute to the chance that an error could occur. By pinpointing the source of these errors, new strategies could be implemented to reduce errors in medication administration. INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 3 Pediatric Pain Management Healthcare professionals must continually keep abreast of both current and new medications. As nurses, one of our jobs is to safely administer medications that will benefit the patient. Every nurse must be vigilant about staying educated. The nurse’s job therefore, is to safely and effectively pass medications of all kinds, including pain medication. Introduction More than three million children are treated as inpatients each year in a hospital. Nearly all of them will require some type of medication during their stay. Medication administration involves several steps and the involvement of several professional practitioners. Typically, the physician orders the medication, the unit clerk transcribes the order, pharmacy prepares the medication(s), and the nurse administers it. Medication errors are possible with each of these steps and with each practitioner. For example, the physician might order .5 mg of morphine for a two-year old but omits the leading zero. The unit clerk reads the order as 5 mg and sends the order to pharmacy. The nurse working has not worked in the pediatric ward before and administers 5 mg instead of 0.5 mg. The child suffers severe respiratory depression and nearly dies. Why is this topic so important? There are a higher percentage of medication errors in the pediatric population with more potential to do harm. “For adults, the reported incidence of errors in treatment with medication ranges from 1% to 30% of all hospital admissions or 5% of orders written. In pediatrics however, this number has been reported to be as high as 1 in 6.4 orders” (Committee on Drugs and Committee on Hospital Care, 2003, p. 431). INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 4 Assessment of Healthcare Environment “A medication error is a failure in the treatment process that leads to, or has the potential to lead to, harm to the patient” (Aronson, 2009, p. 513) When one is reviewing medication errors, it is important to consider the hospital’s policies in place regarding the administration of medications. Typically, most practitioners will use the child’s “weight or body surface area, age, and clinical condition” to calculate the correct dose of medication for that child (Kletsiou et el., 2014, p. 2). It is an essential nursing skill to obtain an accurate height and weight on each pediatric patient. By adhering to the hospital’s policy regarding what factors to use to appropriately dose a child’s medication, it lessens the chance of making a medication error. Nurses must know and adhere to the facilities policies when it comes to all aspects of medication administration. Another newer way to help reduce medication errors is computer charting rather than paper charting. Computer charting eliminates trying to decipher handwritten orders, making the chart accessible to all those involved in the patient’s care, and can provide correct doses of a medication automatically. Understanding that not all hospitals utilize computer charting, it must be noted that charting “varies according to the hospital policy” (Gonzales, 2010, p. 556). Some hospital facilities recommend or even require paper charting for certain situations, but will depend on the situation. Quality and Safety “Medication safety is a major concern and a global issue as regards the quality and safety of patient care” (Chen et al., 2014, p. 822). Combining both facility policies and resources will hopefully reduce the risk of medication errors. Patients are dependent INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 5 upon nurses for ensuring their safety while being hospitalized. Patients expect and deserve the utmost quality of care, especially as it pertains to this issue. Safe medication administration will always be a concern to the practicing nurse and the five rights should always be observed. Challenges One of the biggest challenges for nurses is minimizing human error when it comes to administering mediation. Multiple resources and policies are available for nurses to remind them the associated risks of medication administration error. These resources include protocols, pharmacy department support, posters, and fellow nurses. Another challenge that exists within the healthcare field of medication administration is the common fear of overdosing a child with medication; especially pain medication. This also causes concerns regarding under-medicating the patient for his or her pain. It must be noted that within interdisciplinary approaches, physician’s pain orders may be “insufficient to pre-medicate patients before procedures” (Czarnecki, Hainsworth, Salamon, Thompson, 2014, p. 293.) Understanding that the challenges of human errors are ongoing, one must consider the background of each incident and why it is occurring. The nurse administering the medication might get side-tracked, be extremely busy, or perhaps assume she or he has a correct vial of medicine when in fact it is one that is very similar in appearance to what he or she thinks. It is easy to assume that pediatric patients require less medication as compared to an adult. This is not always accurate. One must consider how the medication dosage is calculated. The background of the patient must be taken into consideration also. Each INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 6 patient tolerates medication differently and it should not be assumed that all pediatric patients that are the same age and same weight will necessarily need the same dose. Inferences, Implications, and Consequences “While the emphasis on pharmacological knowledge and medication safety is essential, equal importance should be given to system failures that impact patient safety. Instructors should assist students to solve conflicts with staff nurses. Procedures for medication preparation that are prone to errors should be discussed with administrators in the clinical placements” (Lee, Lin, Lin, & Wu, 2014, p. 748). When analyzing the literature, one can find that there are many sources contributing to the issue of pediatric medication errors. There are studies that analyzed student nurses, registered nurses, and physician’s pharmacological knowledge to try to understand the source of the issue. One meta-analysis study found that out of six studies researched, “9,167 drug administrations, the random effect error was 20.9%” (Kletsiou et el., 2014, p. 9). If one calculates that rate of medication errors among pediatric patients done in this study, that’s a total of 1,916 patients. It’s a difficult number to comprehend, but hopefully implementing strategies and increasing the awareness of risks of medication administration, can reduce errors in the pediatric population. Further analyzing the research, other viewpoints concur that more pharmacy education is necessary in nursing programs. A study concluded that, “evidence-based results demonstrate that pediatric nurses have insufficient knowledge of pharmacology” (Chen et al., 2014, p. 821). The study based this finding upon the insufficient education of nurses after observing them in the clinical setting. The finding was also based on improper use of double-checking medications with other registered nurses. However, INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 7 this study failed to point out outliers contributing to medication errors. “Its disadvantage is that it concentrates on human rather than systems sources of error” (Aronson, 2009, p. 515). One must consider the overall picture in pediatric medication errors rather than one source. It is a collaborative issue that needs to be resolved and it is essential to discover the sources. Theory Base Nursing Theorist A nursing theorist whose research would be beneficial to help reduce pediatric medication errors is Katharine Kolcaba. The theory that she researched is called the Theory of Comfort and is defined as “the immediate experience of being strengthened through having the needs for relief, ease, and transcendence met in four contexts of experience (which are physical, psychospiritual, social, and environmental)” (Kolcaba, 2010). From an interdisciplinary approach, pediatric pain management involves everyone in the child’s care. That includes the, nurse, and any ancillary personnel. Each one of these healthcare professionals has to be held accountable in managing the child’s pain effectively and safely. According to Kolcaba, the need for relief (pain relief, for example) is an expectation from the patient. By withholding medication or giving less than the necessary amount because one doesn’t want to overdose the child could have adverse effects. Yet many physicians today are still under medicating pediatric patients for pain. Communication is essential in preventing medication errors. “Communication between the members of the multidisciplinary team regarding medication errors should INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 8 be focused on adoption of common definitions for medical errors and their categories, staff education in recognizing medication errors, and implementation of error reporting” (Kletsiou et el., 2014, p. 11). By adopting these common definitions spoken about in the journal, many errors could be avoided. Common definitions, for example, would be including a leading zero in front of a decimal, standard abbreviations, etc. Common definitions would definitely lead to much better communication between health providers. Non-Nursing Theorist A non-nursing theorist that relates to managing pediatric pain before and after surgery is Jerome Bruner. His theory of Discovery Learning is defined as when “the learner draws on his or her own past experience and existing knowledge to discover facts and relationships and new truths to be learned” (“Discovery Learning,” 2009). From an interdisciplinary viewpoint relating to this theory, it takes the knowledge and experience of everyone involved in the pediatric patient’s care to avoid medication errors. For example, when a child undergoes a surgical procedure, pre-operatively, the nurse is in charge of managing pain effectively and safely. In surgery, it’s the anesthetist’s job to manage the patient’s pain, and post-operatively, that responsibility returns to the nurse. Throughout this process, previous experience and knowledge is utilized in assessing the pediatric patient’s safe dose of medication. Also, the physician must be aware of the safe ranges of medication to administer in order to therapeutically manage the child’s pain. To reduce the risk of medication errors, the experience and knowledge of everyone involved in the patient’s care must be fully utilized. By gathering this INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 9 knowledge, medication errors can be reduced and hopefully avoided. This is true especially for nurses as they are the most likely individuals to administer the medication. Policies and guidelines need to be followed, especially when administering high-risk medications such as heparin or insulin that when given in the wrong dose could potentially be fatal. The knowledge that Bruner describes builds on previous experience and exposures. The nurse with more experience and exposure to common pediatric medications is less likely to error in the administration of medication than the nurse with less experience and exposure to the pediatric population. Recommendations for Quality and Safety In recommending strategies to reduce the percentage of pediatric medication errors, policies and interventions have been implemented by healthcare facilities. Policies such as filling out incident reports have been implemented nationwide throughout healthcare facilities. It must be noted that due to the fearful nature of disciplinary procedures such as incident reports, “makes it difficult in detecting errors” (Aronson, 2009, p. 516). Relating this idea back to Bruner’s theory of Discovery Learning, a nurse would not be able to learn from retrospective incident reports unless he or she is aware of the error and the consequence(s) of that error. Incident reports should not be viewed as punishment but rather as a learning tool to prevent further errors of the same kind. Incident reports are most helpful if nurses objectively fill out the report whether it be regarding another nurse or themselves. Another intervention that could be used to reduce the chances of making medication errors in pediatrics is the use “computerized prescribing systems” (Aronson, 2009, p. 519). Having pre-drawn intravenous medication would reduce the risk of human INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 10 error in administering medication. With technology becoming a growing industry within the healthcare field, it isn’t unrealistic to imagine computers drawing up medications instead of the nurse. But reliable equipment can always become faulty, which is why continuous education for nurses must be in place regarding medications. Lastly, another intervention that could be used is the application of the “nine rights (adding four more rights: action, form, response, and documentation) instead of the five rights for safer medication administration” (Lee, Lin, Lin, & Wu, 2014, p. 748). American Nurses Association (ANA) Standards There are three ANA standards that may be applied in the practice setting to reduce pediatric medication errors. These standards are: education, communication, and resource utilization (American Nurses Association, 2010, p. iv). Education is important regarding the reduction of making a medication error. A nurse who is well versed in all aspects of pediatric medication would be much less likely to commit a medication error and if one does occur, will be more likely to know how to treat it. In nursing school, one is taught that pediatrics is its own subcategory of patient care. Pediatric patients require different dosages, approach, and assessment skills to provide effective care. When a nurse is educated about medication administration, he or she is applying “skill appropriate to the role, population, specialty, setting, or situation” (American Nurses Association, 2010, p. 49). The second standard that should be applied to practice is communication. The standard of communication is described as when “the registered nurse communicates effectively in a variety of formats in all areas of practice” (American Nurses Association, 2010, p. 54). When a nurse can communicate effectively amongst other health INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 11 professionals and ask for reassurance, the nurse “improves the professional practice environment and healthcare consumer outcomes” (American Nurses Association, 2010, p. 56). The third ANA standard that is related to this issue is resource utilization. Resource utilization is defined as when “the registered nurse utilizes appropriate resources to plan and provide nursing services that are safe, effective, and financially responsible” (American Nurses Association, 2010, p. 60). In using the resources and policies provided by the facility, medication errors can be reduced. With these resources, the nurse identifies the “needs, potential for harm, and complexity of the task” with each medication pass to their pediatric assignment. (American Nurses Association, 2010, p.60). Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) There are a total of six QSEN competencies: “patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, evidence based practice, quality improvement, safety, and informatics” (QSEN Institute, 2014). Two of these competencies can be directly applied to the issue of pediatric medication. Those competencies are patient-centered care and safety. The competency patient-centered care is applicable to the issue of pediatric medication errors because the higher level of competence of the nurse in the field of pediatrics, the lower the medication error rate will be. Pediatrics is a specialty that demands specific skills of the nurse. Those skills may include being able to communicate effectively, approaching care, or trustworthiness. Acquiring traits such as these can only help the nurse develop a strong rapport with the child. With that INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 12 establishment between the nurse and the pediatric patient, the nurse may be more familiar of the child’s medication dosage thus reducing the risks for medication error. The second QSEN competency of safety is the foundation to avoiding medication errors in pediatrics. By abiding to safety precautions, policies, and resources, a nurse can be competent in maintaining safety while passing medications. There are guidelines in place and errors “can be prevented by the use of check-lists, fail-safe systems, and computerized reminders” (Aronson, 2009, p. 516). Conclusion Pediatric medication errors are a concern within the nursing healthcare profession. As a nurse, it is important to place safety nets around the pediatric patient when passing medications. Safety nets to prevent such errors are available through hospital resources and written policies, but as a nurse, one must implement them in practice. Using the knowledge obtained, focusing on centered-patient care, and addressing the “nine rights” of medication administration will hopefully reduce the chance of error in pediatric care (Lee, Lin, Lin, & Wu, 2014, p. 748). INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 13 References American Nurses Association. (2010). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (2nd ed.). Silver Spring, MD: Author. Aronson, J.K. (2009). Medication errors: what they are, how they happen, and how to avoid them. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 102(8), 513-521. Chen, I., Lan, Y., Tang, F., Wang, K.K., Wu, H. (2014). Medication errors in pediatric nursing: Assessment of nurses’ knowledge and analysis of the consequences of errors. Nurse Education Today, 34, 821-828. Czarnecki, M.L., Hainsworth, K.R., Salamon, K.S., Thompson, J.J. (2014). Do Barriers to Pediatric Pain Management as Perceived by Nurses Change over Time? Pain Management Nursing, 15(1), 292-305. Discovery Learning (Bruner). (2009). Retrieved July 16, 2014, from http://www.learn ing-theories.com/discovery-learning-bruner.html. Committee on Drugs and Committee on Hospital Care. (2003). Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics, 112(2), 431-436. Gonzales, K. (2010). Medication Administration Errors and the Pediatric Population: A Systemic Search of the Literature. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 25, 555-565. Kletsiou, E., Koumpagioti, D., Matziou, V., Nteli, C., & Varounis, C. (2014). Evaluation of the medication process in pediatric patients: a meta-analysis. Jornal de Pediatria, 90(4), 344-355. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/scien ce/article/pii/S0021755714000540. INPATIENT PEDIATRIC 14 Kolcaba, K. (2010). An introduction to comfort theory. In the comfort line. Retrieved July 16, 2014, from http://www.thecomfortline.com/. Lee, T.Y., Lin, F.Y., Lin, H. R., Wu, W.W. (2014). The learning experiences of student nurses in pediatric medication management: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 34, 744–748 QSEN Institute. (2014). Pre-licensure KSAs. Retrieved from http://qsen.org/ competencies/pre-licensure-ksas/.