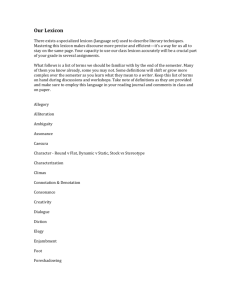

The Northeast Lexicon updated May 2015

advertisement