O`Sullivan 506 Artifact MP

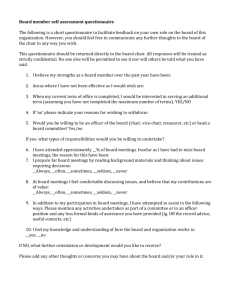

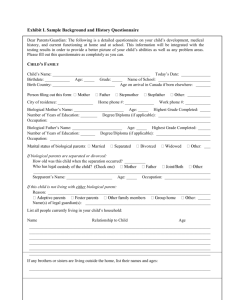

advertisement

Stephanie K. D. O’Sullivan IRLS506 Paper 2 29 April 2012 “Recruitment of Librarians Into the Profession: The Minority Perspective” In this article, Lois Buttlar and William Caynon examine the results of a questionnaire sent to library professionals, paraprofessionals, and students who are members of four distinct minority groups (African-American, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American). The questionnaire asks the participants about various things that may have motivated them to become involved in the library profession, and draws conclusions from the results. However, as Abraham Bookstein notes in his article “Questionnaire Research in a Library Setting,” the use of questionnaires as a social research tool is fraught with errors in reasoning and fallacious conclusions drawn from data of questionable validity. Bookstein examines faults in both sampling and in response, and Buttlar and Caynon’s study exhibits many of these faults. For starters, not only did their methods of sampling vary (while three pools of potential respondents came from memberships in professional library associations targeted toward specific minority groups, the Native American list was “furnished by a Native American involved in recruitment activities” (Buttlar and Caynon 266). After randomly selecting respondents to whom to mail the questionnaires (except in the case of the Native Americans; they had a pool of only 21 and therefore each person in that group was sent a questionnaire), the researchers received only a 55% response rate. Though these can’t be easy groups from which to draw samples, perhaps including all four groups led to a survey that was too broadly applied. For instance, another researcher might drop the Native American aspect after not being able to get a suitable pool—the researchers even had to adjust their results to accommodate this disproportionate pool [Buttlar and Caynon 266]. Results drawn from the responses have their faults as well. For many conclusions, the researchers mention Chi square tests (sometimes in support of evidence, and sometimes just to point out a lack of correlation). Some conclusions seem to be drawn from insufficient data, however; for example they state that “Hispanics seem to be the latest group to enter the field as 54% of them are under age 40” (Buttlar and Caynon 267), however the questionnaire (provided as an appendix in the article) does not ask the respondents at what age they entered the field. One might imagine this conclusion, then—and the researchers do use the word “seem”—but the inclination is not to put much stock in it. This is just one of many rather large leaps made by the researchers from the data they gathered. Also of issue is the questionnaire itself: while many of the prompts seem rather straightforward and unambiguous, there are five “yes or no” questions that leave no room for reasoning or middle-of-the-road opinions or details. Bookstein mentions the risks of “yes or no” questions in his article, citing among their faults the fact that they force a response even when the respondent “doesn’t have a yes/no response to give” (Bookstein 28). Finally, Bookstein suggests that while a questionnaire can be a valuable instrument in studies, their numerous flaws in execution render them essentially ineffective in most cases if used alone. While this study can start to form ideas about their two objectives (to determine both influencing factors and effective recruiting techniques to increase minority representation in librarianship as a profession), it does not offer much along the lines of concrete assumptions about minorities in the profession because of its small sample size and an almost overly simple instrument. Additionally, given that the paper was published in 1992, some of the study’s older respondents would have grown up or even entered the profession in a very different social climate for minorities in the United States. I would be curious to know what marketing strategies and influencers worked on then-current students. “Public Library Development in the United States, 1850-1870: An Empirical Analysis” In this article, Robert Williams uses a wide variety of census data and attempts to use the demographic data to determine the causes of the “widely recognized” spread of libraries and information availability in the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. He examines a wide variety of factors (all available in the census data) such as education, urbanization, and industrialization, among others. In his study of this census data, Williams attempts to find empirical evidence supporting other scholars’ suggestions that factors such as economic ability, education, urbanization (et al) (Williams 179) are what contributed to the sudden growth in libraries during that period. Given the difficulty of studying such a change during the specified time period—it bridges the American Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation—Williams attempts to adjust various factors such as education and literacy. For example, in these and related factors, he considers only the white population in 1850 data, the free population in the 1860 data, and the total population in the (post-Civil War) 1870 data. In doing so, he eliminates a number of outliers that would exist in the earlier data when most black people were still slaves and largely illiterate. He clearly outlines the adjustments made to accommodate race or age (though sometimes the reasoning behind the age variations is unclear). However, there are numerous other factors to mar the comparability of these years, including confusion during some census years of what constituted a “library” (affecting the accuracy of the data on the number of libraries total). As a result, public library data from 1860 had to be eliminated (Williams 181) even though public libraries were cited as the focus of the study (178). In the tables depicting the mean and standard deviation (derived from totals from individual states compared) and national totals for the libraries, it is clear that the standard deviation is quite a lot higher than the mean in much of the data, implying rather broad sets of data. This is to be expected, as Williams is comparing states, and in the late 1800s (and arguably, even now) the individual states in the US were likely not particularly comparable in many of the categories examined. As such, with the wide array of data that is not always comparable between census years, Williams concludes that the question of what caused such a spur in library grown is complicated and remains to be answered. He determines that “library development is a complex phenomenon” (p 197) and that the true causes are not the same for different types of libraries, societies, or time periods. He asserts that additional research is needed to more fully determine what spurred growth during this time period. References Bookstein, A. (1985). Questionnaire research in a library setting. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 11(1), 24-28. Buttlar, L., & Caynon, W. (1992). Recruitment of librarians into the profession: The minority perspective. Library & Information Science Research, 14(3), 259-280. Eldredge, J. (2004). Inventory of research methods for librarianship and informatics. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 92(1), 83-90. Williams, R. (1986). Public library development in the united states, 1850-1870: An empirical analysis. Journal of Library History, 21(1), 177-201.