Uncle Tom`s Cabin or, Life Among the Lowly: A Book that Changed

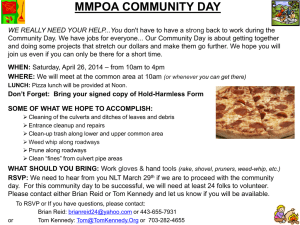

advertisement

Uncle Tom’s Cabin or, Life Among the Lowly: A Book that Changed America In the decade before the Civil War, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe, became an American bestseller. In fact, it was the most successful book, after the Bible, ever published in the United States, with sales mounting into the millions. Stowe registered the title with the Library of Congress in 1851. The Rare Collections Library copy, at the State Library of Pennsylvania, was published by the John P. Jewett Company in Boston. In 1852, during the year after its publication, three hundred thousand copies were sold in the United States and a million were sold in Great Britain. It was subsequently translated into dozens of languages. It is probably no exaggeration to say that, together with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a major cause of the Civil War. 1 Harriet Beecher Stowe was a daughter of the famous New England Presbyterian preacher Lyman Beecher. She later married the biblical theologian Calvin Ellis Stowe, a professor at Lane Theological Seminary in Cincinnati, where her father was the seminary president. Stowe first became acquainted with the “peculiar institution” of American slavery while living in Cincinnati, where she encountered runaway slaves, abolitionists and “conductors” of the Underground Railroad on her trips across the Ohio River into Kentucky. After her husband’s appointment to the faculty of Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine in 1850, the family moved back to New England. During the controversy that year over the Fugitive Slave Act, her sister-in-law, Isabella Beecher, challenged Stowe, saying, “[I]f I could use a pen as you can, I would write something that will make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.” Stowe resolved to do so. But, the key incident that prompted her to write was a vision she experienced while seated at the communion table of the college church. She reported “suddenly” seeing in her mind’s eye the death scene of Uncle Tom, an epiphany so moving that she wept aloud. Returning home, she immediately began to write out the vision that entered her mind “as by the rushing of a mighty wind.” Later she maintained that “The Lord Himself wrote it. I was but an instrument in his hand.”2 The first part of the novel Stowe wrote was actually its conclusion, which she offered to Gamely Bailey, the editor of an anti-slavery newspaper, the National Era. Bailey, who knew the Beecher family in Cincinnati, accepted the incomplete manuscript of Uncle Tom’s Cabin 1 Downs, Robert B., Books That Changed America (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1970), p. 89. 2 Ibid., p. 90. 1 and agreed to pay $300 for it. The novel was to appear serially in the newspaper, in what Stowe expected to be three or four sketches. Instead the series grew to forty installments, extending from June, 5, 1851 to April 1, 1852.3 The story of Uncle Tom’s Cabin is relatively simple, although it is told through a multitude of complex characters richly developed through the situations they encounter. The central characters are Uncle Tom, a loyal, intelligent middle-aged African-American with a deeply religious character and the lovely young mullato slave named Eliza. The story opens in the border State of Kentucky, where Mr. Shelby, a Kentucky farmer and benevolent slave owner, is forced to sell some of his best slaves to a cunning slave dealer named Haley to cover his debts. Among them is Uncle Tom and Eliza’s young son (and only child) Harry. Uncle Tom is resigned to his fate to be “sold down the river;” but, rather than lose her only child Eliza determines to escape across the Ohio River to Ohio and afterward to Canada. While Eliza is first pursued by the slave dealer Haley, and later by a slave hunter named Tom Loker, she is sheltered and helped on her way by Ohio Quakers. Around that time she is also reunited with her husband George Harris, who had escaped a vindictive master. Meanwhile Uncle Tom arrives in New Orleans, where he is sold to a kind young master Augustine St. Clare. Although unhappily married, St. Clare cherishes a loving and pious young daughter Evangeline, who becomes Tom’s mistress. Tom lives happily with the St. Clare family for two years, growing close to his master St. Clare and his young mistress Eva. By and large Stowe’s characters are caricatures with exaggerated moral qualities. Nevertheless, they grow and develop over the course of the story through the varied challenges they encounter. Perhaps the central lesson of the story is the author’s insight that human slavery demeans and dehumanizes both slave and master. The many compromises and rationalizations of slave owners, slave dealers and by-standers (even northerners!) causes Stowe, in the voice of a by-stander, to ask, “[W]ho, sir, makes the trader? Who is most to blame? The enlightened, cultivated, intelligent man, who supports the system, of which the trader is the inevitable result, or the poor trader himself? You make the public sentiment that calls for his trade, that debauches and depraves him, till he feels no shame in it; and in what are you better than he? (p. 161). Stowe develops this thesis in the conversations of her characters. In New Orleans, for example, St. Clare debates the slavery question with his northern cousin Ophelia. Although 3 Ibid., p. 91. 2 a slave owner, St. Clare believes he is unbiased, while his cousin is, in fact, prejudiced. In order to help her see that her views of African-Americans are biased, he purchases a rude young slave girl named Topsy, whom he asks Ophelia to educate. Topsy’s education benefits both teacher and student. After two years, Eva becomes ill and dies. But in her last days she experiences a vision of heaven, which she shares with those around her. As a result of vision and her testimony, many of those around her, slave and free, resolve to change their lives. Ophelia throws off her prejudice against blacks, Topsy determines to better herself and St. Clare pledges to free Tom. However, St. Clare soon follows his daughter in death, and before he can follow through on Tom’s promised emancipation, he dies while intervening in a dispute in a neighboring café. After St. Clare’s death, his wife Marie reneges on her husband’s promise to Tom, and sells him along with the other slaves on the plantation. Tom has the misfortune to fall into the hands of a wicked plantation owner, Simon Legree, who takes Tom to his plantation in rural Louisiana. Tom earns his master’s enmity when he refuses to beat his fellow slaves. Legree brutally beats Tom instead, determined to quash his faith. Still, Tom continues to read his Bible and comfort his fellow slaves. When Tom’s body and spirit are nearly broken by Legree’s constant cruelty and the hardships of plantation labor, he is refreshed by a vision of Jesus that renews his hope. Even Legree notices the change in his attitude, and remarks, “What the devil’s got into Tom . . . ? A while ago he was all down in the mouth, and now he’s peart as a cricket.” (p. 457) Tom is clearly a “Christ figure” within the narrative. He encourages, even inspires, his fellow slaves by his witness and example. Ultimately, at the cost of his own life, Tom protects Legree’s escaped slaves Casey and Emmeline by refusing to disclose their whereabouts. Legree threatens Tom, asking him, “Well, Tom! [D]o you know I’ve made up my mind to kill you?” Tom calmly responds, “It’s very like, Mas’r.” When Legree offers to spare his life if he tells him what he knows about the escaped women, Tom stands silent before him. “Speak,” screams Legree, striking him in fury. “Do you know anything?” Tom responds, “I know, Mas’r, but I can’t tell anything. I can die!” (p. 479). Suppressing his fury, Legree, with a cold determination, takes Tom by the arm and delivers him to his overseers Sambo and Quimbo to be beaten to death. Like Christ his savior, Tom forgives his torturers; a forgiveness that ultimately convicts and converts them. 3 Uncle Tom’s Cabin, although a simple, formulaic nineteenth-century sentimental novel, challenged American readers by the power of its imagery, its ideas, and its characters. The ideas, while radical and threatening to the social order, south and north, were delivered in moral and theological terms that were familiar to most Americans. For this reason Stowe touched the American psyche, and helped to set in motion events that would lead to war, redemption and (more than a century later) to African-American freedom. Uncle Tom’s Cabin is just one of the titles described in Robert B. Downs’ 1970 publication Books That Changed America. Several other titles among the State Library’s rare and transitionally rare holdings that appear in this book include Jane Addams’ Twenty Years at Hull-House (1910), Frederick Winslow Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management (1916) and H.L. Mencken’s Prejudices (1919). Some of these titles will, no doubt, be profiled in this column. The Rare Collections Library is open to students and researchers by appointment, MondayFriday, between the hours of 9:00 am and 12:00 noon, and 1:00 pm-4:00 pm. To make an appointment, contact Dr. Iren Snavely by telephone at 717.783.5982, or by email at: irsnavely@pa.gov. The Rare Books reading room is also open periodically for tours to the general public and to Pennsylvania Commonwealth employees. 4