Selecting Narrative Methods File

advertisement

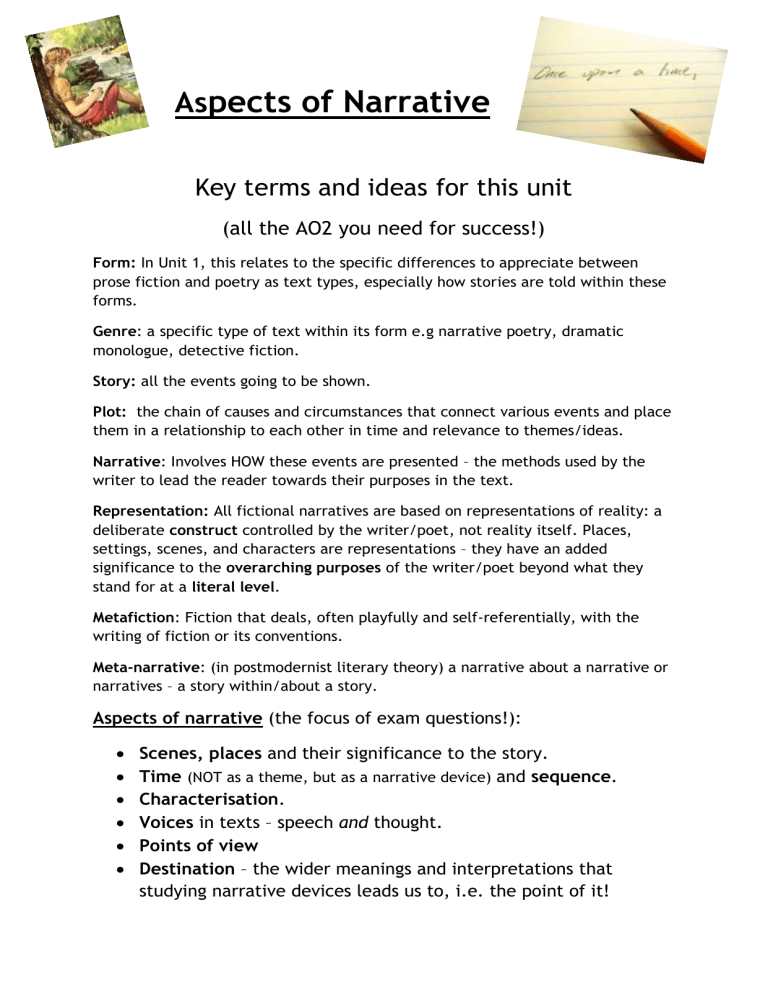

Aspects of Narrative Key terms and ideas for this unit (all the AO2 you need for success!) Form: In Unit 1, this relates to the specific differences to appreciate between prose fiction and poetry as text types, especially how stories are told within these forms. Genre: a specific type of text within its form e.g narrative poetry, dramatic monologue, detective fiction. Story: all the events going to be shown. Plot: the chain of causes and circumstances that connect various events and place them in a relationship to each other in time and relevance to themes/ideas. Narrative: Involves HOW these events are presented – the methods used by the writer to lead the reader towards their purposes in the text. Representation: All fictional narratives are based on representations of reality: a deliberate construct controlled by the writer/poet, not reality itself. Places, settings, scenes, and characters are representations – they have an added significance to the overarching purposes of the writer/poet beyond what they stand for at a literal level. Metafiction: Fiction that deals, often playfully and self-referentially, with the writing of fiction or its conventions. Meta-narrative: (in postmodernist literary theory) a narrative about a narrative or narratives – a story within/about a story. Aspects of narrative (the focus of exam questions!): Scenes, places and their significance to the story. Time (NOT as a theme, but as a narrative device) and sequence. Characterisation. Voices in texts – speech and thought. Points of view Destination – the wider meanings and interpretations that studying narrative devices leads us to, i.e. the point of it! Scenes and places Places are representational Setting stories in places is important to a connection with readers’ lives. The signification of place: Settings have added significance beyond just paces where events happen – how do authors exploit the possibilities of settings to create meaning? Consider the relation of setting to wider issues. You can explore setting on a literal, associative and symbolic level. Consider the ‘road/journey’ setting as a common device: the ‘life is a journey’ metaphor. Dialect: regional and social variations in language (how characters are shown to speak depending on place). Eye-dialect: the representation of the lexis, grammar, syntax and phonology of a particular dialect in writing in a way the reader can understand (as opposed to the phonetic symbols a linguist uses to represent individual sound in a dialect). Prose VS. Poetry Prose: readers expect detailed descriptions and realisations of places and scenes. There’s also an expectation of places and scenes being ‘believable’ and ‘realistic’. Poetry: due to concision of narrative in this form, specifics of a place can be given without details of precise location. Realism in setting is less vital to the readers’ response. Time and sequence The time the story is set in. Time covered by events in the story. The order of those events Time is ‘managed’ by the writer in fictional worlds so it can be: Speeded up Slowed down Compressed (over whole narrative) Rearranged Repeated Time can be represented in chronological order in a narrative: may be defined by sub-genre. There’s ambiguity about when a story really ‘starts’ or ‘ends’ anyway. Stories can be told retrospectively – looking back on something. Framing: setting one story up ‘inside’ another. A writer’s choice of how to manage time and sequence can result in foregrounding of certain events, characters, feelings etc. Prose VS. Poetry Prose: meaningful establishment of time and sequence. Poetry: often characterised by meaningful absence of specific time/sequence. Characterisation People in fictional worlds (writer’s constructs) have levels of significance. Characters in fiction are there for a purpose. Characters are representations of people – they are not real. Their reality is an illusion. How do writers/poets establish, create and exploit character for their purposes? External methods: Looking at signification in names – these can be linked to culture/time. Looking at cultural stereotypes Significance of character appearance (physical description) Speech habits/dialogue Eye-dialect Internal methods: Thoughts/motives of characters (often implied) Memories Dreams Establishment of character early on in a text. Prose VS. Poetry Prose: readers expect detailed realisations of characters. There’s also an expectation of characters being ‘believable’ and ‘realistic’. Poetry: due to concision of narrative in this form, specifics of a character can be given without details of precise background. Points of view Starting point = Is it narrated in third or first person? Prose VS. Poetry Consider the advantages and limitations of these approaches. Prose: readers expect detailed descriptions and realisations of places and scenes. There’s also an How can using free indirect thought/speech or multiple narrative voices be used? expectation of places and scenes being ‘believable’ and ‘realistic’. Poetry: due to concision of narrative in this form, specifics of a place can be given without Visual/spatial metaphors are significant in narrative points of view: details of precise location. Realism in setting is less vital to the readers’ response. Point of view is based on a deeply-embedded visual/spatial metaphor of being in a particular bounded space; what we see and how we see it depends on where we are in that space and the direction we are facing – our point of view. Can also relate to the assumptions in texts based on Narrative voice can affect this. beliefs and values: the ideology presented in a text. Proximity to action: narrative point of view can be varied for effect based on how ‘close’ a reader feels to the action. Semiotics: The significance of connotations and how they create meaning. Pronouns: ‘you’, ‘we’, ‘our’ etc. can tell the reader a lot about narrative point of view. Poetry vs. Prose Poetry tends to keep to one/two points of view as it condenses narratives = potential for ambiguity: story might alter meaning if told from a different point of view. Titles are significant to point of view – can be interesting to explore. Voices in texts Speaking and thinking both lead to voices in texts Voices are part of how writers tell readers about characters First person narrator: tells the story reflects on the significance of events expresses emotion over events Third person narrator: can access a wider range of characters, experiences, thoughts, places and times. Omniscient narrator: an ‘all‐knowing’ kind of narrator found in works of fiction written as third‐person narratives - has a full knowledge of the story's events and of the motives and unspoken thoughts of the various characters. He will also be able to describe events happening simultaneously in different places. Centre of consciousness: technique of telling the story wholly or chiefly from the point of view of one individual, though the narrative is still third-person. Speech and attribution Direct speech: actual words spoken by a person. Indirect speech: speech reported by a narrator giving a version of the words spoken. Attributed speech: when the speaker is identified. Free speech: speech that s not attributed to a specific speaker. You can combine these to class speech as free indirect, direct attributed speech etc. Poetry vs. Prose THOUGHT: Prose can give a reader the detailed thoughts of a character; it’s something the reader can access if the writer wants them to. Poetry can also achieve this up to a point. Destination What’s the point of studying narrative methods? Where does the writer want the reader to ‘end up’ by the choices they’ve made? How do the narrative choices lead the reader to interpretations and to wider conclusions that are meaningful? In the fictional world of stories (vs. the real world): There a greater sense of overall purpose. There’s a greater sense of wholeness and completion at the ‘end’. Consider ‘the journey of reading’ – an interesting metaphor for the process and experience. Contexts of production Contexts of reception How do these considerations relate to how interpretations are arrived at? Other useful narrative terms: Didactic voice/tone Dual perspective Stream-of consciousness Digression Shifts in perspective Colloquial Direct address Turning point Pivotal Lexis Lexical Semantic Figurative language Hook Allusion Internal monologue Hook Parallels Unreliable narrator Bildungsroman